Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowGrowing up in rural Georgia, Kimberlee Adsit never parallel-parked a car, but Celadon Group Inc. taught her how to place the length of a tractor-trailer against a curb.

The 22-year-old recently earned her commercial driver’s license and was rewarded with a new cap, signed by instructors and classmates in Celadon’s Quality Drivers school. Elated about passing the exam, Adsit wore the cap with pride.

Instructor Maura Slater helps a student at Celadon’s training facility. The trucking firm hopes training its own drivers will cut down on turnover. (IBJ photo/Aaron P. Bernstein)

Instructor Maura Slater helps a student at Celadon’s training facility. The trucking firm hopes training its own drivers will cut down on turnover. (IBJ photo/Aaron P. Bernstein)“This proves that hard work pays off,” she said.

An average of 35 trainees a week arrive at Celadon’s east Indianapolis headquarters hoping to replicate Adsit’s success. Desperately in need of drivers, the company reels them in with transportation, housing, meals, training and the promise of employment.

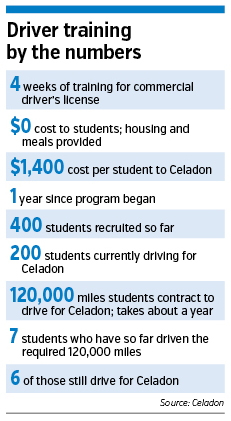

Celadon launched its in-house truck-driving school a year ago to boost the supply of drivers and, executives hope, cut down on turnover, which is 98 percent per year at the company, mirroring the industry average. As more of its competitors take the same tack, Celadon is relying on small perks to set its school apart and keep drivers on its payroll.

“They’re new people coming into the industry; they don’t know what to expect,” said Danny Williams, vice president of Celadon’s Quality Cos. subsidiary, which runs a truck dealership network and lease-to-own program. “If we pay them well, give them a good life, they’re not going to leave us.”

“They’re new people coming into the industry; they don’t know what to expect,” said Danny Williams, vice president of Celadon’s Quality Cos. subsidiary, which runs a truck dealership network and lease-to-own program. “If we pay them well, give them a good life, they’re not going to leave us.”

Many of the trainees arrive with little money in their pockets, so the $50 that Celadon gives them to cover weekend meals makes a big difference, school manager Scott Vogel said. And the company makes sure to put them up in decent motels, he said.

By next year, they’ll stay in a dormitory that’s under construction down the road from Celadon’s headquarters on East 33rd Street. The $5.25 million building will include basketball and racquetball courts and a driver lounge and business center.

Several larger trucking companies, including Swift Transportation of Phoenix and Stevens Transport of Dallas, run their own schools and make the same basic offer of free food, housing and training.

Celadon requires four weeks of basic training toward the CDL exam, a company orientation and six weeks of supervised driving. The program is free, as long as recruits fulfill a contract to log 120,000 miles—about a year’s worth of driving—for the company. Other companies require a two-year contract, and they may dock drivers’ pay to recover the tuition, Williams said.

“We try to put the person in the position where they’re making money out of the gate,” Williams said. “I think that’s what truly separates us.”

Celadon has recruited 400 trainees so far, spending an average $1,400 per person. That’s still cheaper than recruiting experienced drivers, which runs $3,000 to $4,000 per person because of advertising and sign-on bonuses, Williams said. The cost of training will decline further once the new building opens, he said.

Celadon will continue competing for experienced drivers, but it needs as many trainees as it can recruit in order to meet growing customer demand, Williams said. The pipeline of fresh trainees also gives the company leverage to hold its 3,000 current drivers to higher standards.

The American Trucking Associations estimates the driver shortage at 20,000 to 25,000 on a base of 750,000 trucks in the over-the-road market. The industry predicts that shortage will grow to 239,000 by 2022.

The industry cites several reasons, starting with a difficult lifestyle—drivers spend only four full days a month at home. Trucking firms have to be selective about hiring, and new federal regulations, which kicked in this summer, effectively limit the number of hours drivers can spend on the road in a week.

Drivers are paid by the mile, so even as trucking firms raise their per-mile rates, other trends hold down drivers’ total earnings, said Bob Costello, chief economist for the ATA. Major retailers have opened more warehouses across the country, so truckers make shorter trips and spend more time dropping off loads.

Because of the changing conditions, Costello said, “More companies are looking at drivers with no experience in the industry.”

Celadon advertises that new drivers can earn as much as $45,000 their first year. The company requires them to work in two-person teams, which together must drive 240,000 miles. Each team member earns 18 cents per mile. The teams are eligible for monthly bonuses that can add up to another $3,060 per person.

Vogel said the pay is two or three times what many trainees were earning in their old jobs. While that might be attractive to some people with few other options, it’s not enough to solve the industry’s perceived shortage, Ball State University economist Mike Hicks said.

“The wage is part of what makes it unappealing,” he said.

Hicks is skeptical that the industry faces a true shortage, because truckers’ pay hasn’t risen significantly. From 2008 through 2011 in Indiana, heavy-duty truck drivers’ earnings rose 1.8 percent, while those driving light-duty and delivery service saw their earnings rise 3.3 percent, he said.

That suggests the long-haul trucking firms simply aren’t paying enough, possibly because that would raise their costs and send customers to competing modes of transportation like rail, Hicks said.

Costello disagrees that trucking is under pressure from rail competition, but he said it’s true that drivers’ wages aren’t rising quickly.

“When the economy starts growing at a faster pace, pay is going to go up, and go up significantly,” he said.

Adsit is not overly concerned about how much money she’ll make. Along with her parents, Mark and Carolyn, she came to Celadon looking for a change in lifestyle after her brother, Marine Cpl. Coty Sockalosky, was killed in Afghanistan.

The tight-knit family heard about Celadon’s school from one of Coty’s buddies, who drives for the company, and they decided it would be nice to see the country, Carolyn Adsit said. The trainers have been surprisingly patient and accommodating, she said.

“I can’t say enough about how they’ve treated us.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.