Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowCONVERSE—A clean, white barn with red trim breaks the repetition in the acres of farmland that define Converse, Indiana. On its face, a sign—printed with sunflower patterns and the company’s name, Healthy Hoosier Oil—hints to passersby what products come out of the Miami County facility 20 miles west of Marion.

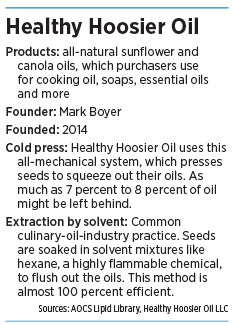

Right now, that oil comes from sunflower and canola seeds and is produced mostly for culinary purposes. But someday, the product mix might include hemp oil.

At least that’s what company owner Mark Boyer hopes.

“I’m a sixth-generation commodity crop farmer,” said Boyer, who has lived in the Converse farmlands his entire life. “We still farm two separate tracts that my ancestors settled about 1840, right here, and we’re still here farming those same tracts. That’s something that we’re very proud of.”

But Boyer also represents a break in tradition. First, he diversified his 350-acre farm by processing oil.

Now, he is the first non-university player in Indiana hemp research.

Mark Boyer's first hemp seedlings have begun to sprout. (Photo courtesy of Mark Boyer)

Mark Boyer's first hemp seedlings have begun to sprout. (Photo courtesy of Mark Boyer)On June 7, Boyer planted 300 pounds of hemp seed—obtained through a Purdue University researcher—on a 10-acre plot. The plants will mature later this summer, when he will take their seeds and turn them into hemp oil—and hemp oil only. Under the research rules, he can’t use the rest of the plant.

The results could affect the future of hemp farming in Indiana.

Overall, 36 states—including Indiana—allow hemp agriculture in some capacity, whether that entails research or a commercial industry, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Indiana’s southern neighbor, Kentucky, has been a leader in the Midwest’s hemp industry for years, where hundreds of licensed growers are farming more than 12,000 acres of hemp.

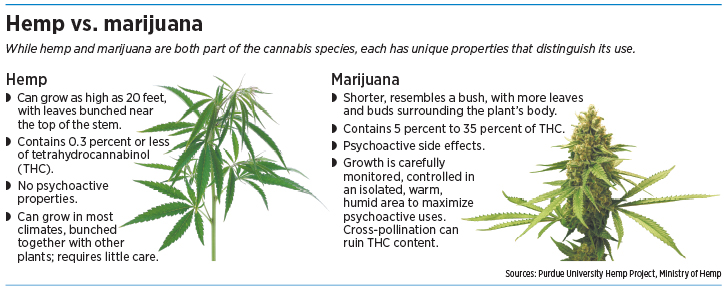

But Indiana has more restrictive rules about growing the plant, which is in the cannabis family but doesn’t contain the same hallucinogenic properties as its cousin marijuana.

Until now, Purdue University was virtually the only Indiana entity to grow and study hemp.

That’s largely due to Indiana’s hesitancy about diving into a crop whose seeds the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration classifies as a controlled substance. A 2014 state law opened the door to hemp production here, but licenses went only to accredited research groups.

Ronald Turco, head of the agronomy department at Purdue’s College of Agriculture, said he is the only person in the state with a Schedule I research license, a certification issued by the DEA that allows him to import hemp seeds for research.

Turco

Turco“We are the primary point of contact for industrial hemp in the state of Indiana,” Turco said. “I mean, it’s the Wild West, in terms of what’s going on right now. … There are 50 states and there are 50 sets of rules, and that’s the problem.”

This month, Boyer obtained permission from the Indiana seed commissioner and the Indiana State Chemist’s Office to purchase, plant and manufacture hemp oil from seeds imported by Turco.

Boyer hired attorney Justin Swanson to help him navigate the process. Swanson, a member of the Indiana Hemp Industries Association’s board and founding member of the Midwest Hemp Council, helped Boyer apply for the two certifications—a processing license, which allowed his company to receive seeds imported by Purdue, and a growing license.

The pair submitted the first application on April 27. Boyer received his final license via mail on June 4, days before the seeds would arrive in Lafayette.

The bureaucratic hurdles won’t end there, Boyer and others said. But neither will the opportunities.

Support and dissent

In their 2018 legislative session, Indiana lawmakers considered several hemp-related measures.

Most supporters saw the passage of Senate Bill 52—which legalized the possession and use of cannabidiol, or CBD oil—as a turning point. CBD oil can be extracted from hemp.

S.B. 52 expanded a 2016 measure, backed by Republican Sen. Blake Doriot of Elkhart County, that legalized the product in treatments for epilepsy patients.

Doriot

DoriotNow that the alternative therapy is open to a wider audience, Doriot said the state should make it easier to produce the CBD oil within its borders.

“It’s very possible in Indiana,” he said. “We do things in this state. We don’t sit back idle.”

But hemp farming is not just about CBD.

Flexform Technologies, a company in Doriot’s district, manufactures textiles from hemp. It currently imports thousands of pounds of hemp fiber from operations in Europe and Asia. To sustain Flexform’s operations, Indiana’s farms would have to produce 80,000 pounds of the fiber every week.

Another bill introduced last session, House Bill 1137, would have allowed widespread farming of industrial hemp. But after Gov. Eric Holcomb expressed concerns about regulation, the Senate voted to send the issue to a summer study committee.

Pro-hemp lawmakers said they hope the study will assuage public officials’ worries about how to regulate the industry. After all, other states are doing it.

But Bruce Kettler, director of the Indiana State Department of Agriculture, said it would be “very difficult” to emulate another state’s regulations, given Indiana’s agency setup.

Kentucky, for example, had a more central regulatory system under its Department of Agriculture from the start. Indiana farming is regulated by multiple agencies, which means the Agriculture Department would need to coordinate with the Chemist’s Office and the Indiana State Police should hemp be legalized.

Jeffrey Cummins, director of public affairs for the Agriculture Department, said an increased presence of federal guidelines might help state lawmakers reconsider hemp.

Capitol Hill might issue a clearer opinion by the end of the year. A 2018 farm bill, piloted by Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and set to be discussed this summer, includes provisions that could remove hemp from the DEA’s controlled-substances list.

The family feud

Republican State Rep. Bill Friend, who represents Boyer and his family, said industrial hemp has opponents largely because people misunderstand its relationship to marijuana.

Friend

FriendHe offered a comparison: Imagine, Friend said, having a cousin who is always in trouble with the law or involved in a scandal. That bad reputation could spill onto the rest of the family.

This relationship can be applied to hemp and marijuana, he said—two scientifically different varieties of the same family. Friend said fear about legalizing marijuana drives baseless opposition to hemp, a product that doesn’t contain high enough levels of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, to give users the “high” associated with marijuana.

Now-popular CBD oil is derived from the hemp variety of cannabis, specifically from the flower buds that protrude at the top of the stem. From there, producers manufacture an oil that supporters say can alleviate ailments, including anxiety, epilepsy, chronic pain and inflammation. CBD contains little to no THC, with Indiana’s current laws mandating that CBD oils show no more than 0.3 percent THC content.

Boyer doesn’t manufacture CBD—and has no plans to do so.

Kettler

KettlerInstead, he wants to produce oil from hemp seeds that would add a new flavor, texture and nutrients—including protein and amino acids—to edible products like salad dressing.

Big Indiana retailers, including Kroger and Target, already sell products from Boyer’s operation. And Piazza Produce distributes his all-natural sunflower and canola oils to many Indiana restaurants.

Boyer said the potential impacts of CBD oil are “a very exciting component to industrial hemp, but that’s not what we’re going to do here.”

“We’re farmers. We grow food,” he said. “That’s what we do.”

Boyer’s role in the hemp research comes with some risk. While Purdue researchers will oversee the project and conduct studies on the crop, Boyer is funding the effort.

He first selected a seed supplier in Wisconsin. From there, he purchased the seeds for $1,200. And, while his test space is relatively small, the project requires him to take some crops out of rotation for the season.

Additionally, because Boyer’s facility has only one $10,000 cold-press machine—used in his preferred, all-mechanical method of extracting oil—he will have to delay sunflower and canola oil production in order to test-process the hemp seeds. That poses a potential loss to the farm’s $78,000 annual revenue from sunflower and canola oil.

Additionally, because Boyer’s facility has only one $10,000 cold-press machine—used in his preferred, all-mechanical method of extracting oil—he will have to delay sunflower and canola oil production in order to test-process the hemp seeds. That poses a potential loss to the farm’s $78,000 annual revenue from sunflower and canola oil.

Hemp’s growing season is about four months long; the plants begin to mature in earnest after the summer solstice on June 21, as daylight decreases. The crop is usually harvested in August.

The research also costs time. Aside from Purdue, which must send representatives to oversee certain steps in the project, Boyer will partner with the Indiana State Police to test the crops’ THC levels.

While Boyer obscured the hemp plot as much as possible, preparing an area five miles from his central facility, police will also provide day-and-night security patrols to deter trespassers who might mistake the hemp for marijuana.

Spreading awareness

Boyer’s project is just one part of the larger effort to bring hemp back to Indiana.

“What was the third-largest crop in Indiana in 1935?” Jamie Campbell Petty asks a crowd at Centerpoint Brewing Co. in Indianapolis.

“Hemp,” a few members in the crowd echo. “Hemp!” another voice shouts.

“Our goal is to bring back hemp in Indiana,” Petty responds.

Petty helped found the Indiana Hemp Industries Association in 2014, as a branch of the 20-year-old national Hemp Industries Association. She was one of the many pro-hemp faces at a Hemp History Week event June 6, sponsored by Petty’s organization and Circle City Connect, a networking community for young Indianapolis professionals.

In the brewery’s meeting space, guests could help themselves to free samples of hemp-based products, including soaps, raw seeds, paper and CBD oils. Pamphlets describing pro-hemp groups were scattered on the hardwood tables. A raffle even awarded one guest a basket filled with hemp products.

Jessica Scott, executive director of the Indiana Hemp Industries Association, planned the event to encourage Indianapolis residents to learn more about the movement.

Jessica Scott, executive director of the Indiana Hemp Industries Association, planned the event to encourage Indianapolis residents to learn more about the movement.

Scott first learned about hemp when changing her diet. During her time at the University of Indianapolis, she turned to vegetarianism, then to veganism, in an effort to enhance her health and well-being. Hemp, she noted, was the greatest source of plant-based protein she could find.

“I got involved very early on, I would call it the ground floor of the industry, as things were forming,” she said.

Since then, the conversation about hemp has been weighed down by layers of complexity but also increased public awareness. She said public enthusiasm was responsible for passing Indiana’s newest rules for CBD oil. Now, her job is to encourage that same support for a wider hemp industry.

Annie Rouse, a board member of the Kentucky Hemp Industries Association and founder of an online CBD oil shop, Anavii Market, said Indiana will find success when, like Kentucky, it bridges the divide between farmers’ needs and public opinion.

As Kentucky’s tobacco industry started to die out at the turn of this century, hemp offered a profitable alternative, she said. But it wouldn’t have been possible without the work of farmers, including her own father, who championed the movement.

As president of the Indiana Farmer’s Union Hemp Chapter, Marty Mahan could fit the role Rouse called a crucial step in hemp deregulation.

Like Boyer, Mahan is a multi-generational farmer. He lives and operates a commodity crop farm in Rush County.

His responsibility in the farmer’s union, he said, is to educate his peers about the uses, costs and restrictions of hemp farming. He predicted that about 70 percent of farmers would grow hemp if it were made available. But, even with some progress at the state level, Mahan said he is unsure whether Indiana will initiate an industry on its own.

“I have absolutely no idea what will come out of this summer study and where it will go,” he said. “It took us 80 years to sell beer on Sundays. There’s a part of me that thinks Indiana won’t move forward until the federal government moves forward.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.