Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe massive American Senior Communities fraud case might never have come to light were it not for a nearly century-old Indianapolis company that had a chance to participate in the overbilling and kickback scheme but called the FBI instead.

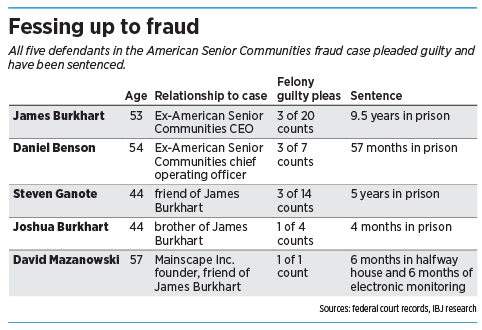

IBJ’s review of recent court filings and its interviews with federal prosecutors and the FBI bring to light a host of new facts about the three-year-long inquiry, which culminated this month in the sentencings of five defendants to a total of nearly 20 years in prison.

Federal prosecutors give a tip of the hat to David Bratton, the president and chief operating officer of Business Furniture LLC, who called the FBI in June 2015 after being recruited to join the scheme by one of the defendants, Steven Ganote.

Bratton then turned over emails and other records and agreed to record phone conversations, one of which captured Ganote implicating his friend James Burkhart, the CEO of nursing home giant American Senior Communities.

Burkhart

BurkhartOn one recording, Ganote told Bratton that, in return for the privilege of doing business with the state’s largest nursing home company, he should inflate invoices and then pay the overages to a limited liability company. “Just between you and me, if this is just between you and me, [James Burkhart] is part of the LLC. That’s all you need to know.”

From there, the FBI was off and running. Using information obtained from Bratton, investigators paid a visit to another vendor, a friend of Burkhart’s named David Mazanowski, founder of the Fishers-based landscaping company Mainscape Inc., Assistant U.S. Attorney Cindy Cho said.

After FBI agents made a surprise visit to his home at 7 o’clock one evening, Mazanowski immediately acknowledged guilt and flipped, even though prosecutors at that point hadn't known he'd done wrong. He soon was wearing a wire at breakfast meetings with Burkhart at which the CEO repeatedly incriminated himself.

“Those two cooperators and the information they provided, along with the covert recordings they were able to make, provided critical evidence in this case,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Nicholas Linder, who led the prosecution with Cho.

Linder

Linder“Without human cooperators, we don’t make cases like this, or they’re a lot harder to make. So the support of the public and citizens doing the right thing is absolutely critical to our law enforcement mission.”

Mazanowski—who was sentenced to the lightest punishment of any of the defendants—declined to comment.

Roger Harvey, a spokesman for Business Furniture, said in a statement: “When they saw this, they really felt in their heart of hearts they needed to do the right thing, and that’s what they did.”

The raids

The investigation splashed into the headlines on Sept. 15, 2015, when more than 100 law enforcement personnel fanned out across the Indianapolis area to execute search warrants at American Senior Communities’ Gray Road headquarters, Burkhart’s Carmel home, Ganote’s Hendricks County home and other locations.

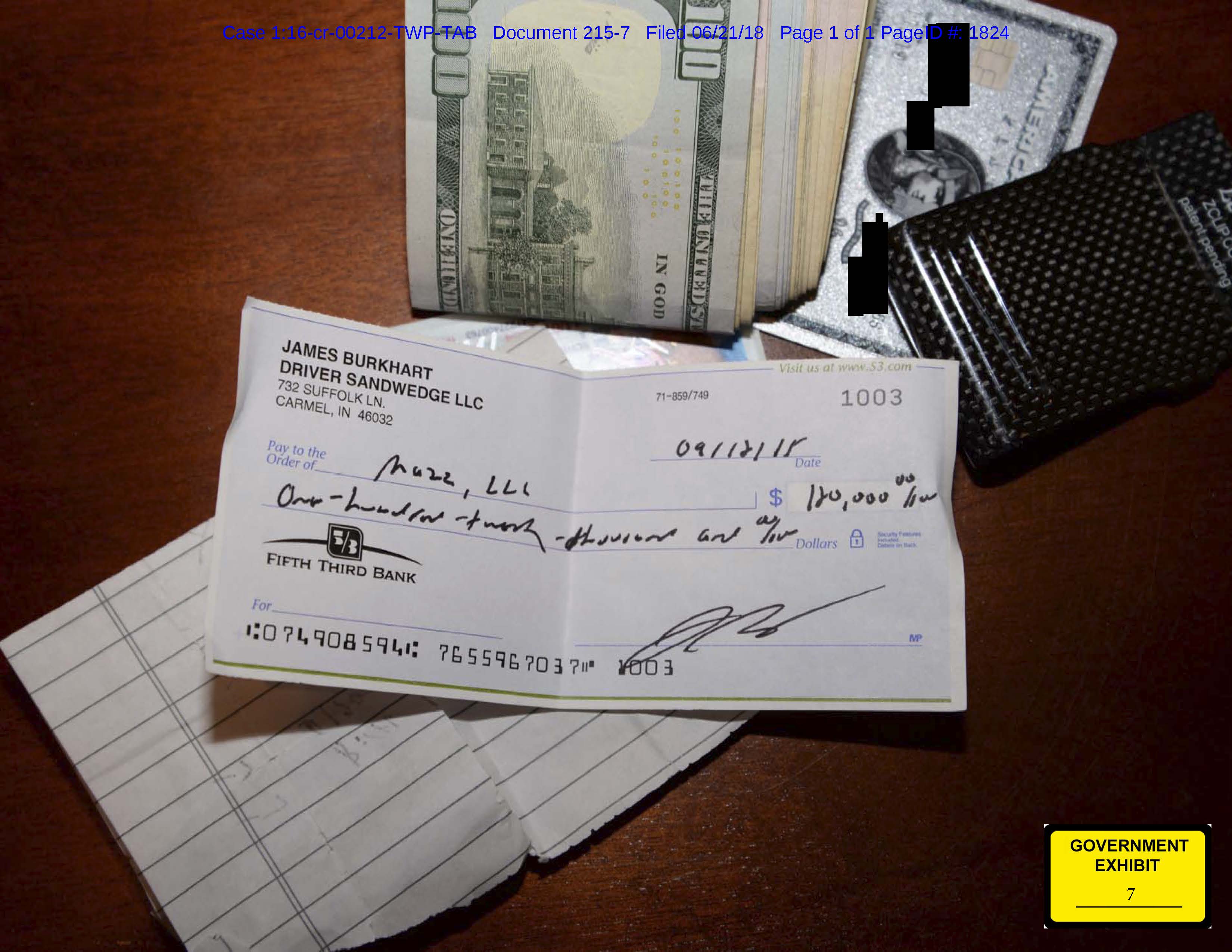

That morning, Burkhart, Ganote, Mazanowski and others had planned to fly on a private plane to the BMW Championship golf tournament in suburban Chicago. In Burkhart’s backpack for the trip was more than $14,000 in cash and a handwritten ledger in which he estimated he would receive $5.5 million from fraud and kickbacks in 2016 alone, according to a filing by prosecutors.

Cho

ChoIn Burkhart’s home, office and safe deposit box, investigators found other largesse, including 150 gold bars, 200 gold coins and more than $1 million in cash.

Prosecutors unveiled charges in the fall of 2016 against Burkhart; former American Senior Communities Chief Operating Officer Dan Benson; Mazanowski; James Burkhart’s younger brother, Joshua; and Ganote—alleging they used shell companies and other deception to orchestrate a $19 million overbilling scheme that ran from 2009 until the day of the 2015 raids.

In all, Burkhart took part in more than two dozen overbilling and kickback arrangements, according to prosecutors. The kickbacks covered all sorts of purchased goods and services, from landscaping and nurse call lights to American flags and hospice services.

On American Senior Communities stationery that investigators seized in the raid, Burkhart had listed some of the various schemes, adding as the final entry “God knows what else”—potentially indicating he was seeking additional opportunities.

The victims of the fraud were American Senior Communities, which is owned by the Jackson family of Indianapolis; the Health & Hospital Corporation of Marion County, which hired ASC to operate its nearly 70 nursing homes; Medicare; and Indiana Medicaid.

All five defendants submitted guilty pleas without going to trial. Judge Tanya Walton Pratt, who sentenced the five this month, came down hardest on James Burkhart, sentencing him to 9-1/2 years. Benson and Ganote each received about five years, while Joshua Burkhart got four months and Mazanowski received six months in a halfway house, followed by six months of electronic monitoring.

Prosecutors say the amount of fraud and kickbacks totaled $19 million, but the actual loss to victims was smaller—about $12 million—all of which the government expects to recoup. It’s already seized or received cash, real estate, jewelry and other items worth roughly $7 million.

Never enough

It is not clear what led Burkhart, who appeared on top of the world professionally, to succumb to rampant fraud.

By the time he started working for American Senior Communities and the Jacksons in 2001, Burkhart—the son of a Catholic school principal in Milroy—had developed a national reputation in the health care industry.

Prosecutors say his annual salary was $1.4 million. In addition, from 2002 to 2015, the Jacksons—an intensely private family with holdings in a range of industries, from oil and gas to self-storage units—paid him more than $7.4 million in consulting fees on acquisitions and other business deals, according to a filing by his attorneys.

James Burkhart had been scheduled to fly to a golf tournament on Sept. 15, 2015, the date investigators raided his home. A backpack packed for the trip had more than $14,000 in cash in it. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Attorney’s Office)

James Burkhart had been scheduled to fly to a golf tournament on Sept. 15, 2015, the date investigators raided his home. A backpack packed for the trip had more than $14,000 in cash in it. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Attorney’s Office)Yet it is clear from transcripts of wiretapped conversations filed in court that Burkhart was angry the Jacksons didn’t shower him with many more millions of dollars.

In a wiretapped conversation between Mazanowski and Burkhart at Another Broken Egg at 9435 N. Meridian St., Burkhart said the family should have paid him another $22 million over the past 15 years, given the profitable empire he helped build and the terms under which he believed he should have been compensated.

“Everybody’s just taking money from me,” Burkhart told Mazanowski during the August 2015 breakfast. “And they’re taking it from my people, too, which pisses me off. But I’ll get mine. I always told ya, I’ll get mine one way or another.”

During the meal, Mazanowski asked whether ASC’s owners would examine financial records and notice the highly inflated expenses. Burkhart scoffed. “Nobody ever does. Nobody ever looked at them before,” he said. “Nobody’s that smart. Ain’t that smart.”

Shelia Guenin, Health & Hospital’s senior vice president for long-term care, said her organization was told by the FBI early on that the fraud scheme was sophisticated and would have been very hard to detect.

“I believe we were monitoring our business,” Guenin said. Even so, “There are things we have learned. We have added additional controls. We have added additional staff to our corporate compliance department. We are doing additional audits, and ASC has done the same.”

The Jackson family declined to be interviewed for this article, though an American Senior Communities spokeswoman issued a statement saying the company “is grateful for the justice that was served in the legal case against its former executives. As reported previously, their actions never impacted the quality of care of the residents we have the privilege to serve.”

Greg Massa, the FBI assistant special agent in charge who led the investigation, said the defendants’ thievery should serve as a wake-up call for other employers.

Massa

Massa“No matter what controls you have in place, make sure you check those controls again,” he said.

“This type of fraud happens when there is an opportunity. There has to be an opportunity to gain access to funds.”

Other defendants

Prosecutors cast Burkhart’s brother Joshua as a relatively minor player in the fraud who received about $400,000 by sharing in James’ deals.

A filing by the government goes so far as to cast blame on James for Joshua’s legal predicament.

James Burkhart’s “greed was contagious—as is too often the case with those who peddle in corruption. The defendant brought in not only his chief operating officer and his friends, he infected his family. He cut in his little brother, and as a result, got him indicted.”

Prosecutors labeled Ganote as the man who ran the financial nitty-gritty of the shell companies and kickback schemes, referring to him as “the quintessential ‘bagman.'”

“If James Burkhart was the conspiracy’s CEO, then Steve Ganote was its CFO, and then some,” a filing said. “He managed the conspiracy’s numerous bank accounts and its proverbial ‘second set of books,’ which he maintained by hand.”

Benson’s role was more of a puzzle. Though he changed his plea to guilty in December 2017, his early July filing arguing for a favorable sentence read as though he were in denial.

Benson’s role was more of a puzzle. Though he changed his plea to guilty in December 2017, his early July filing arguing for a favorable sentence read as though he were in denial.

The filing said that, when Burkhart approached him in 2009 about starting joint ventures that would provide goods and services to American Senior Communities, “Dan had no reason to believe Jim would ever involve him in any improper or illegal conduct. … He believed Jim would have made whatever disclosures were necessary to the Jacksons.”

The filing said that, while the company’s employee handbook included a prohibition against owning or having a significant stake in a supplier, it waived that requirement if the arrangement had been disclosed to the CEO.

“Overjoyed at the prospect of earning more money that he could use for charitable philanthropy, Dan quickly spread the word about the idea among his friends and family members,” the filing said. “Of course, Dan would never have participated in, much less spoken so openly and enthusiastically about, any of the joint ventures had he any inkling they might be improper.”

In retrospect, the filing said, “Dan now understands that he was intentionally kept in the dark about the joint ventures, indeed, was outright lied to by JimBurkhart on many occasions.”

Prosecutors countered in their sentencing filing that “to the extent that the defendant seeks to paint himself as a completely unwitting pawn in the scheme with no self-enriching motivations, the evidence tells a different story.”

While Benson cast himself as charitable, he lived the high life just likeBurkhart, with a 5,000-square-foot, five-acre home in Fishers, a vacation home on Lake Michigan, an apartment rental in SoHo in Manhattan, and a $50,000 Rolex.

“Perhaps the most illustrative evidence of Benson’s consciousness of guilt is the fact that, in interview after interview, not a single ASC employee—including Benson’s two ‘direct-reports’—were aware that he had personal financial interests in ASC’s vendors. Indeed, his employees expressed feelings of disbelief and betrayal upon learning that the man they came to respect had his hand in the till.”

Prosecutors say they found Benson’s arguments curious.

“For sentencing purposes, the more you accept responsibility in general and say, ‘Look, you caught me. This is what I did,’ usually a judge will go lower in the sentence,” U.S. Attorney Josh Minkler said. “I’m not sure that was in his best interest to take that stance after pleading guilty.”

How the fraud worked

Minkler

MinklerProsecutors say the kickback schemes were structured in various ways that didn’t necessarily make vendors aware they were participating in wrongdoing.

For example, Burkhart and Ganote created a shell company called Bright HVAC that became a middleman between the Indianapolis-based HVAC contractor Bright Sheet Metal and American Senior Communities.

Bright Sheet Metal’s owner was told to bill Bright HVAC in order to ensure timely payment. When Ganote received the invoices, he created new invoices with inflated amounts and sent them to American Senior Communities for payment.

Mainscape founder David Mazanowski, who reaped more than $800,000 in the fraud, can claim no such ambiguity.

According to the indictment, at James Burkhart’s direction, Mainscape from 2009 to 2014 inflated landscaping invoices 5 percent and sent them to ASC for payment.

ASC then used Health & Hospital funds to pay the inflated amounts. In turn, Mainscape paid the 5 percent overcharges to Joshua Burkhart’s shell company Circle Consulting LLC.

According to the indictment, James Burkhart and Mainscape upped the ante in January 2015, increasing the overcharges an additional 45 percent. From that point until the scheme ended, James Burkhart and Mainscape kept the overcharges for themselves, splitting them 50-50, with each receiving about $195,000, the indictment alleges.

Furthermore, according to the indictment, Mainscape, at James Burkhart’s direction, from 2009 to 2015 submitted false invoices to ASC for “consulting” services that had not been performed. The payments were actually reimbursements to Mazanowski for James Burkhart’s use of his plane, to reimburse him for a golf trip Burkhart had asked him to pay for, and to reimburse him for political contributions Burkhart had directed him to make.

In total, according to the indictment, about $1.5 million in Health & Hospital funds were used to pay Mainscape for fictitious consulting services.

The reason prosecutors charged Mazanowski—but not any other vendor—is because Burkhart told him exactly what he was doing and shared proceeds of the scam with him, Assistant U.S. Attorney Linder said.

“There was no subterfuge. … He was straight up with Mazanowski, which is why he proved to be a very valuable cooperator.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.