Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowEli Lilly and Co. approached Indianapolis officials last fall with a plan it said would benefit both sides. The drugmaker wanted to invest $159 million to boost its insulin manufacturing operations at its sprawling technical center south of downtown.

The investment, Lilly officials wrote in a PowerPoint, would help the company “meet the growing diabetes demand in the U.S. and abroad” and add capacity for development of new medicines. The project would include nearly 100,000 square feet of construction, along with new manufacturing equipment and building renovations.

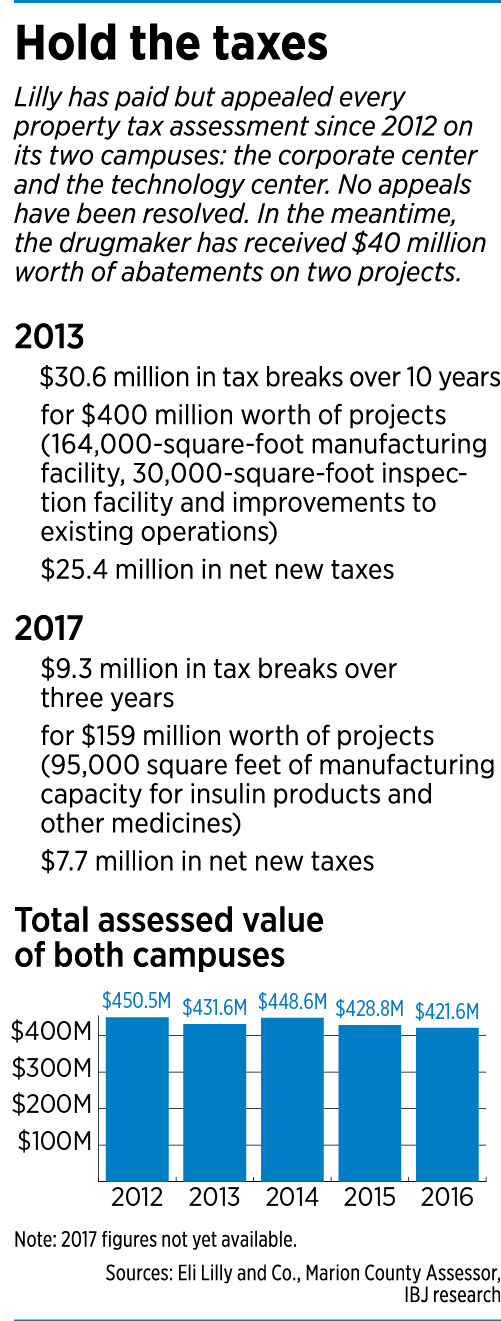

In exchange for the investment, the Indianapolis-based drugmaker wanted a 10-year tax abatement worth $9.3 million.

Qaddoura

QaddouraBut when City Controller Fady Qaddoura, who is responsible for managing the city’s $1.1 billion budget, got wind of the proposal, he sounded the alarm, according to emails obtained by IBJ.

“I am opposed to giving Lilly tax abatements given that they appealed over $20 million in property taxes owed to the city (largest amount of appeals by any employer in Marion County),” Qaddoura wrote on Oct. 4. “We need to resolve the appeals issue with Lilly before we commit to any new tax abatements.”

Lilly, which employs about 12,000 in Indianapolis and is one of the city’s largest property owners, had been appealing its annual tax bill every year since 2012. The company—which owns more than 130 buildings spread across 375 acres at its technical center and corporate headquarters two miles to the east—said the Marion County assessor was high-balling the value of its land and buildings.

For years, Lilly’s appeals have been wending their way through the hearing process, with no end in sight.

For years, Lilly’s appeals have been wending their way through the hearing process, with no end in sight.

If the city loses the appeals, it might have to scrape up millions of dollars to refund Lilly—money the cash-strapped city cannot easily part with.

The emails—obtained through an IBJ public records request—cast a rare spotlight on tensions within Mayor Joe Hogsett’s administration between accommodating one of the city’s oldest and largest companies and protecting the cash-strapped city’s tax base.

Within an hour of receiving Qaddoura’s email, Angela Smith Jones, deputy mayor for economic development, replied, but not with the news he wanted to hear.

Jones said two other high-ranking city officials—Thomas Cook, Hogsett’s chief of staff; and Emily Mack, director of metropolitan development—had “agreed it was wise to proceed and support the abatement for Lilly.” She didn’t explain why.

A few minutes later, Cook chimed in with an email: “Mayor is aware of and has approved” the abatement.

But Qaddoura wasn’t satisfied. He said that if his office weren’t consulted on such matters before the city granted approvals, he might be unable to control the city’s finances and budgets.

“I would appreciate a more coherent decision-making process to ensure that we do not repeat the mistakes of previous administrations,” Qaddoura wrote. “I still think it is not right to give Lilly abatements without proper conversation about their tax appeals.”

His protests went unheeded.

Council approval

At a City-County Council committee meeting Oct. 23, some members expressed concerns that Lilly was not promising to add or retain jobs in return for the abatement. At the time, the company was in the midst of cutting 3,000 U.S. jobs, many of them in Indianapolis, in the company’s largest downsizing in a decade.

“I think about the kinds of things the city pays for with these dollars,” Councilor Zach Adamson said, according to a video of the hearing. “Public safety is a huge one, and schools … and poor relief.”

“Trust me,” he continued, “I am a huge fan of Eli Lilly. I know they do amazing things in this city. But no jobs created, no jobs retained, the possibility of losing hundreds of workers here in Marion County. … It’s difficult for us.”

Mike O’Connor, Lilly’s director of state government affairs, responded that the abatement would allow Lilly to continue to grow over time but acknowledged the company was trimming jobs, not adding them.

“I do want to be frank,” O’Connor told Adamson. “There will be a smaller number of employees here in central Indiana. But we don’t anticipate there will be fewer employees in manufacturing.”

Even so, the committee voted 6-0 to recommend approval to the full council. Two weeks after that, the City-County Council approved the proposal by a 25-0 vote.

Some tax experts call the situation unusual, with Lilly simultaneously appealing its property taxes and asking for a big tax break.

“I just find it a little odd, pushing the envelope a little,” said Kurt Zorn, professor of public and environmental affairs at Indiana University in Bloomington, who specializes in state and local public finance.

He said cities have a right to know whether their tax base is at risk before granting new abatements.

“If I were looking at the overall total assessed value of the tax base of Indianapolis, I’d want to have some certainty before I granted a tax abatement,” said Zorn, who chaired Indiana’s Board of Tax Commissioners under former Gov. Evan Bayh.

Zorn

ZornNet new taxes

This was not the first abatement the city granted to Lilly while the drugmaker was challenging its property tax valuations. In 2013, Indianapolis approved a 10-year tax break worth $30.6 million in exchange for $400 million in investments for new facilities and technology upgrades, also for insulin production. Lilly said it has completed nearly all those projects, and the tax breaks will run through 2023.

Taylor Schaffer, a spokesman for Hogsett, defended the latest abatement for Lilly, saying the city will reap a handsome sum over the long haul—$7.7 million a year in net new taxes as a result of the agreement.

“After internal discussions, there was consensus that it was in the best interest of taxpayers to allow Lilly’s legally entitled property tax appeal process to continue while the city simultaneously pursued significant capital investments in the company’s local campus,” she wrote in an email.

She continued: “Every economic deal, regardless of size, involves thoughtful discussion between City officials. In this instance, we were excited that the city’s continued partnership with Lilly resulted in a $159 million capital investment in Indianapolis and the company’s commitment to further innovation and growth of our city’s workforce.”

Qaddoura did not return phone calls from IBJ seeking comment on whether he still has concerns.

Challenging assessments

Challenging assessments

While the tax abatement sailed through council, the tax appeals are moving at a decidedly slower pace.

“Due to the complicated nature of Lilly’s operations, we have appealed many, but not all of the assessments of our Indianapolis properties in order to ensure the correct calculation of our property taxes,” Lilly spokesman Mark Taylor said in an email to IBJ. “I cannot comment further on the status of any particular tax appeal.”

Marion County Assessor Joseph O’Connor said Lilly has appealed more than $400 million in assessed value each year for the past five years. He said the appeals are inching their way through the department’s review process; none has been resolved.

Appealing a tax assessment is often a slow, painstaking process. A property owner gathers and submits evidence, such as appraisals or sale prices. The information is presented to a hearing examiner at the county's assessment board of appeals. Either side can take the case before the Indiana Board of Tax Review, and even to the Indiana Tax Court. Appeals can go as high as the Indiana Supreme Court.

Neither side would reveal the substance of Lilly’s appeals, nor what evidence the company has submitted to justify lower assessments.

But O’Connor said the county has no intention of backing down.

“We’re not going to cave for the sake of caving,” he said. “Sometimes these things get pushed out and take time to resolve.”

Lilly is far from the only company in Marion County to appeal its assessment—and, by extension, its property taxes. Each year, hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of businesses do the same thing, O’Connor said.

Lilly said it has paid its property taxes every year in full while appealing the assessments. The Marion County Treasurer’s Office confirmed that Lilly paid $43.4 million in 2016 in property taxes. In 2017, it paid $37.9 million.

For the first half of 2018, it paid $19.9 million. For the second half of 2018, it has a bill due of $19.8 million, payable Nov. 13, said Joshua Peters, Marion County’s deputy treasurer of operations.

Unique property

Helping stoke the tax dispute is the reality that Lilly has few if any peers in Indianapolis. Its campuses are like a city within a city, with factories, offices, laboratories, shops, climate-controlled storerooms and museums, along with miles of roads and acres of parking lots.

That leaves little for assessors to compare when they calculate a value. Unlike a home, a restaurant or an apartment building, there are no comparable properties that have been sold or appraised.

“It’s inherently difficult to put a value on a unique property like that,” said Purdue University economist Larry DeBoer.

Other methods of assessing a property—such as guessing at the replacement cost, or looking at rental income on a commercial property, and dividing by a rate return—are also difficult if not impossible in Lilly’s case, he said.

Joseph O'Connor

Joseph O'ConnorAssessing commercial properties of all stripes can be complicated, and it isn’t unusual for property owners that challenge the methodology to score a big refund.

In 2015, Michigan-based supermarket chain Meijer received nine years of refunds totaling $2.4 million after asserting that its bustling store at 8375 E. 96th St. should be assessed as if it were empty, not doing steady business inside. It argued that the store should be compared to a former Lowe’s in Anderson and shuttered Walmart stores in Lafayette, Clarksville and Bloomington.

The Indiana Board of Tax Review ruled that the Meijer store—one of the most successful in the state—should have been assessed in 2012 at the equivalent of $30 per square foot, not the $83 per square foot assigned by Marion County.

In Lilly’s case, it’s anyone’s guess how long it might take to resolve the dispute.

“It’s unfortunate,” the county’s O’Connor said. “I don’t think either party wants it lingering this long. But where there are that many tax dollars at stake, we are going to defend the most fair estimate on that property.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.