Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowSince Carmel Mayor Jim Brainard defeated his last primary opponent, the city’s debt has climbed more than 30 percent, according to the Indiana Department of Local Government Finance.

Back then, in 2015, former City Council President Rick Sharp campaigned against Brainard primarily on the issue of debt. At the time, the city owed nearly $1 billion, including principal, interest and other payments. Sharp even put the number on his campaign signs.

But debt was not a winning issue, and Brainard took 62 percent of the vote.

But debt was not a winning issue, and Brainard took 62 percent of the vote.

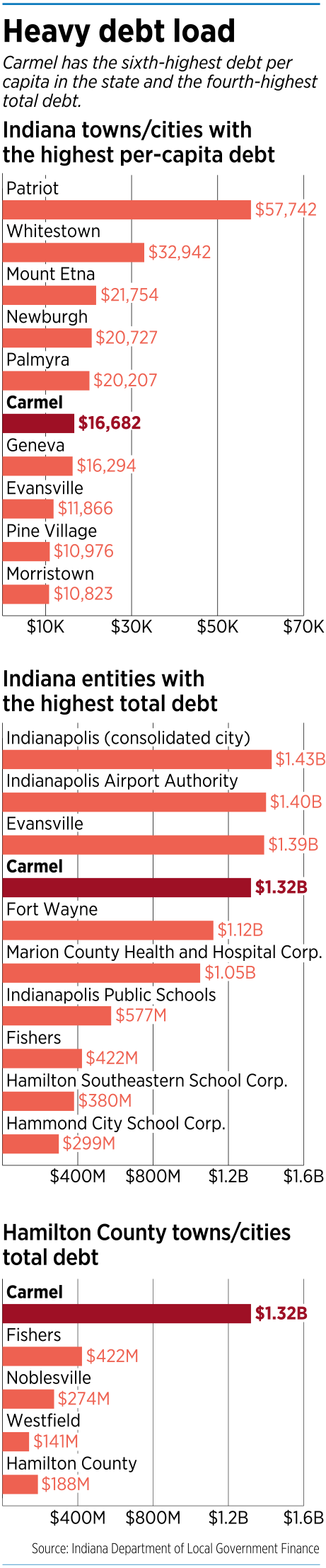

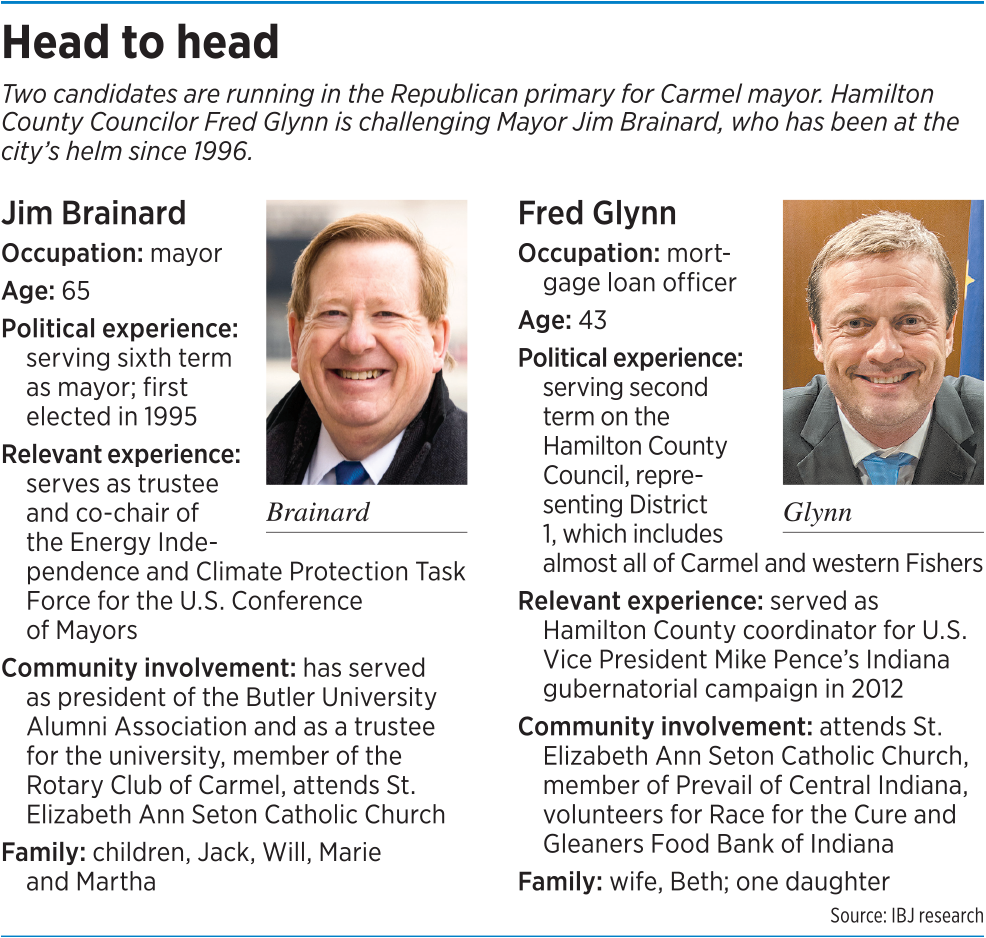

Today, as he seeks a seventh term, the city owes $1.3 billion, according to the DLGF. And a new challenger—Hamilton County Councilor Fred Glynn—is planning to try again to make debt a campaign focus. He also wants officials to be more transparent, and for the city to remain affordable and grant fewer subsidies to businesses.

Glynn contends the city’s debt load is simply too high and “can’t be ignored.” He pointed to Standard & Poor’s 2017 decision to downgrade the city’s credit rating, which Glynn said “should be a warning sign to all residents.”

But Brainard is unfazed and, in fact, has plans—should he win another term—to construct more roundabouts, redevelop at least two important parcels on Rangeline Road, and complete the redevelopment of City Center and Midtown.

He disputes the way the DLGF reports debt and says the city actually owes only $874 million, including $15 million in bonds that will be issued for The Carmichael, a city-owned hotel being constructed near City Center.

He told IBJ the DLGF figure includes interest to be paid and debt assumed by the city utilities, which many cities in Indiana don’t operate. The latter is paid down by user fees, and the utility operates separately from the city budget.

Brainard also said Carmel’s debt load is reasonable for a city its size, especially one that’s seen such rapid growth. The city has grown to 92,000, up from 65,500 at the end of Brainard’s first term, in 2000.

But Brainard’s primary opponents aren’t the only ones raising questions about the city’s debt.

Since the last election, Carmel issued two controversial bond packages worth $96 million, and S&P downgraded the city’s debt rating from AA+ (the second-highest) to AA. The bonds were issued to fund the City Center hotel; a variety of street, path and infrastructure improvements; and land acquisition.

Originally, the city had proposed borrowing $101 million, with the additional money dedicated to purchasing an antique carousel. But public outcry led the city council to eliminate the carousel from the bond package.

An AA rating signifies to lenders that the city has a “very strong capacity to meet financial commitments,” but Standard & Poor’s did say the city’s growing debt levels make it “vulnerable to unanticipated economic or operating swings.”

“The downgrade reflects our view of the city’s rapidly increasing debt burden, with mounting leverage that can pressure flexibility and budgetary performance over time,” S&P Global Ratings credit analyst Anna Uboytseva said in a media statement in November 2017, the last time S&P issued a long-term credit rating for the city.

Tipping point

Glynn is serving his second term on the county council, where he represents District 1, which encompasses nearly all of Carmel and western Fishers. He said he chose to run in May’s primary after an October Carmel City Council meeting he attended during which members allowed the Carmel Redevelopment Commission to purchase the Monon Square shopping center between City Center and Midtown for more than its appraised value.

The seven council members voted 4-3 to approve the $15 million purchase of the shopping center, which the administration plans to redevelop into a mixed-use project similar to those in City Center and Midtown. The average of two appraisals was $11.5 million.

Brainard told IBJ the appraisals were almost a year old, and some parcels in the area were selling for $3 million per acre at the time of the purchase. He defended the expenditure, saying once developed the property is expected to generate about $2.5 million in tax revenue every year, up from about $60,000 now.

Glynn, a mortgage loan officer, said if developers were interested in purchasing the property, the city should have allowed them to do so.

“That to me is completely absurd,” he told IBJ. “Do you think any bank is going to give you a loan if you tell them you want to pay someone $300,000 for a $150,000 house? That’s where I come from is banking. Nobody’s going to do that.”

The property was purchased with proceeds from a $25 million bond issued in 2017 to fund property acquisitions by the CRC.

Glynn said it’s likely even more debt will be accrued to redevelop the parcel if the city builds a parking garage or other infrastructure. The debt will likely be paid with revenue from a tax-increment financing district, which collects new tax revenue generated within a specified zone. Carmel has used TIF dollars to pay debt for other projects.

Glynn said it’s likely even more debt will be accrued to redevelop the parcel if the city builds a parking garage or other infrastructure. The debt will likely be paid with revenue from a tax-increment financing district, which collects new tax revenue generated within a specified zone. Carmel has used TIF dollars to pay debt for other projects.

Glynn said purchasing the shopping center is just one example of the city’s interfering in the real estate market. He said another example is the city’s involvement in building The Carmichael.

The 122-room boutique hotel will be constructed between the Monon Trail and Veterans Way, just south of City Center Drive. The city plans to use $15 million of bond proceeds to pay for a portion of the project, and the CRC will back a $25 million construction loan Carmel-based Pedcor Cos. is obtaining.

Glynn said he won’t criticize every spending decision Brainard had made. He enjoys living in Carmel as well as many of the projects that have been completed under Brainard’s term.

But he said there’s room for improvement, and new leadership could make a difference.

Glynn said that, if elected, he’ll find ways to cut spending to be able to pay off debt sooner.

“You have to take a different outlook” on spending, he said. “Stop bribing businesses to come here. Stop giveaways to private developers. Try to attract businesses here without giving away taxpayer money. I know that’s a crazy concept in Hamilton County these days, but I think it’s something worth talking about.”

Glynn said he and other members of the council are cognizant of the county’s own debt load, which—at $188 million—is lower than that of any of Hamilton County’s four cities. And he said the council uses debt sparingly.

It keeps enough cash on hand to cover 50 percent of the county’s annual property tax collections, putting the county in a sound financial position, Glynn said. And council members don’t shy away from telling commissioners to trim back projects the county can’t afford, he added.

Stacking up

Brainard critics, including Glynn, often compare Carmel’s debt load to that of other Hamilton County cities. Carmel carries not only the most total debt but also the largest debt per capita.

In fact, Carmel’s debt is higher than the other three cities combined, and the city carries the fourth-highest debt load of all entities in Indiana, according to the DLGF.

Yet Carmel still maintains one of the lowest property tax rates in the state, Brainard pointed out, thanks in part to the number of companies contributing to the city’s tax base.

Carmel is home to more than 125 corporate headquarters, which help keep residential property taxes low, he said. Only 4 percent of Carmel’s debt, including capital leases for expenses like police cruisers, is repaid with residential property tax revenue, Brainard told IBJ.

“The great majority is paid for by business taxpayers,” he said. “We’ve used their taxes to build hundreds of millions of dollars of road, water and sewer infrastructure that allow our businesses to expand here.”

Carmel’s 2019 property tax rate of 0.7886 per $100 of assessed value is the 11th-lowest in the state and is comparable to other Hamilton County municipalities, including Fishers and Westfield. Brainard shared with IBJ a Carmel study of local tax rates that showed a homeowner who paid $2,800 in 1998, during Brainard’s first term, is now paying $2,100.

“That’s a good record,” he said.

And Brainard said his administration has practiced good fiscal management, which has “allowed us to do everything else we’re doing in the city to create a high quality of life [and] to provide top-rate services.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.