Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe coalition featured a who’s who of the central Indiana business community.

Leaders from Eli Lilly and Co., Salesforce, Cummins Inc., Anthem Inc. and more joined forces to pass what they called a comprehensive hate crimes law.

Months later, many are wondering whether they should declare victory or lick their wounds.

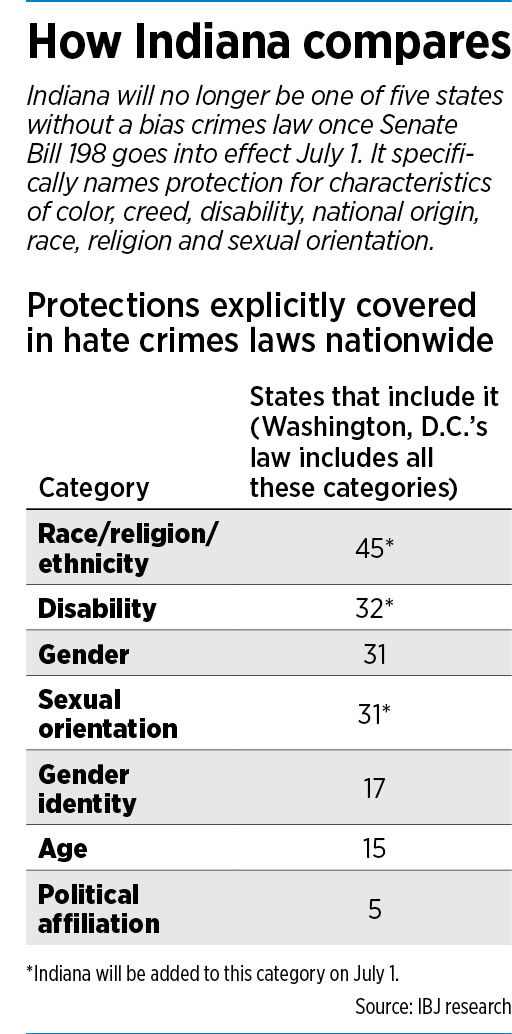

Yes, Gov. Eric Holcomb signed hate crimes legislation into law, a move he says should help with economic development and talent recruitment by moving Indiana off the short list of states without one. And yes, the Indiana Chamber of Commerce signed on to the final bill.

But the law doesn’t actually meet all the criteria the Indiana Forward coalition established. Most notably, it doesn’t specifically—and the key word is specifically—say that crimes motivated by a victim’s gender or gender identity are eligible for harsher penalties.

And that’s left many in the coalition promising to return to the Statehouse next year to fight for a broader list of victims.

Whether they will be successful in the near future, though, remains up in the air. Lawmakers already fatigued by the divisive debate could be unlikely to take it up again so soon. Religious conservatives who oppose language giving what they believe are rights to transgender people are not likely to bend. And simply having a hate crimes law removes the economic incentive that had driven many of the advocates.

So, what happened? Why couldn’t some of the state’s top companies get the law they wanted?

Some political observers say the campaign could have been better—more ads, rallies or phone calls—and the group may have expected Holcomb to have more influence than he did. Others say lawmakers and some coalition members probably decided passing something was better than nothing and may have let up on their demands near the end of the process.

Downs

Downs“It would have been, I think, easy for some members of the Legislature and/or the governor to take a hard line stand and say, ‘No, we need a list or we need the following items included in any legislation,’” said Andy Downs, director of the Mike Downs Center for Indiana Politics at Purdue University Fort Wayne.

“But they are individuals who understand the legislative process and recognize that sometimes you take the small bit of pie you can get and then come back later on for another slice of pie,” he said.

And that’s exactly what advocates are promising to do. But it may be more difficult to rally public support in the future if people believe the issue has already been handled.

“Will this be the big public fight in future sessions? I don’t know,” Mark Fisher, chief policy officer for the Indy Chamber, said. “And I don’t know that if it’s not, that it’s necessarily a bad thing.”

Fisher

FisherFor now, businesses may be disappointed in the outcome of the legislation, but they aren’t disappointed in their lobbying effort.

“I have no regrets,” Fisher said. “And I’m very proud of what we were able to do. I don’t know what more we could have done to advance this legislation.”

What went wrong?

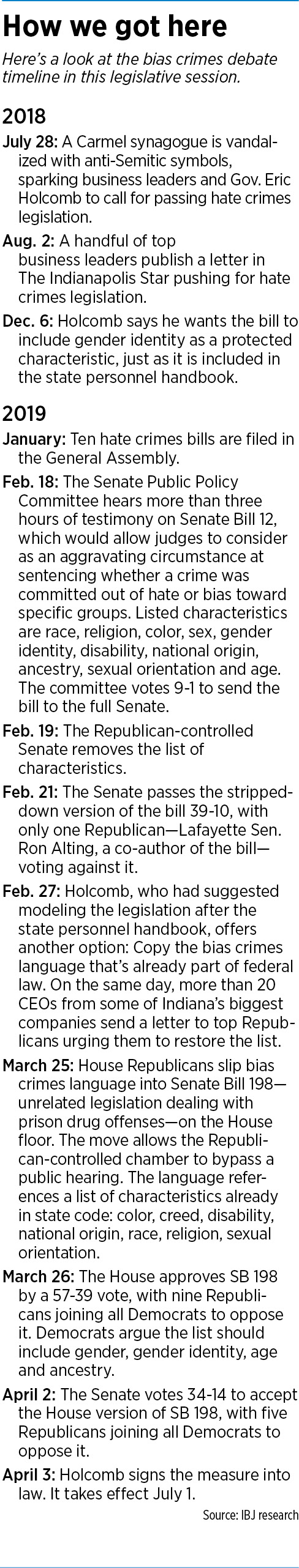

The process started well for advocates, when the Senate Public Policy Committee voted to send a bill with a list of specific characteristics—including gender identity—to the full chamber. But then Senate Republicans—who represent a supermajority of the chamber—stripped the list from the legislation before passing it.

After that somewhat unexpected and significant change, some political observers criticized the campaign for not doing enough in terms of calls to lawmakers, rallies or public advertisements. Holcomb also received some pushback for not doing enough to influence Republican lawmakers.

Mike O’Connor, senior director of state government affairs for Lilly, said he heard complaints that lawmakers weren’t being lobbied strongly enough, but he also heard complaints from lawmakers about too many people calling them.

Mike O’Connor, senior director of state government affairs for Lilly, said he heard complaints that lawmakers weren’t being lobbied strongly enough, but he also heard complaints from lawmakers about too many people calling them.

“I know several thousand phone calls were made,” O’Connor said.

After the Senate version passed, business officials started to warn lawmakers that national reaction to the legislation could be as bad for the state’s reputation as the reaction to passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 2015.

After then-Gov. Mike Pence signed that bill into law, national organizations and companies threatened to boycott the state because they believed the law allowed discrimination against people who are gay or lesbian. The outcry led lawmakers to approve changes that quelled most of the opposition.

But even that threat didn’t seem to make a big impact, as some key lawmakers, including House Speaker Brian Bosma, brushed off the concern about another RFRA.

The House action on the bill happened in a way that avoided another round of public testimony. In a procedural move, the Republican-controlled House inserted hate crimes language into an unrelated bill on the chamber floor. That version referenced a list of characteristics that split supporters because it had some specific characteristics they sought, but not everything they wanted.

The language—which would become the final law—made defendants eligible for stronger sentences if their crimes were motivated by a victim's real or perceived characteristic, trait, belief, practice, association or other attribute, including but not limited to a list of specific characteristics already included in state law. That list includes color, creed, disability, national origin, race, religion or sexual orientation.

But it did not include gender and gender identity.

But it did not include gender and gender identity.

The Indiana Chamber issued a statement in support of the language, but the Indiana Forward coalition remained opposed to it.

Still, it may have been the best possible compromise, given that Republicans were in a tug-of-war between economic conservatives that supported a hate crimes law and social and religious conservatives that opposed hate crimes legislation generally and language that protected people based on sexual orientation and sexual identity, in particular.

Conservative social groups such as the Indiana Family Institute and the American Family Association of Indiana argued that hate crime laws are unnecessary and unconstitutional, because they treat some individuals differently than others.

For Republicans in especially conservative districts, voting counter to the wishes of conservative groups could make them vulnerable to primary challengers. For example, in the May 2014 primary election, two Republican state lawmakers— Rebecca Kubacki of Syracuse and Kathy Heuer of Huntington—were ousted after voting against a proposed constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage.

In the end, even the conservative social groups didn’t agree on the final hate crimes language: The Indiana Family Institute opposes it, while the American Family Association of Indiana supports it.

Murphy

MurphyFormer Republican state lawmaker Mike Murphy said it’s easy for divisions to develop while debating social questions, as opposed to tax or economic issues, making it harder for business advocates in this situation.

“I think they know their business [issues] best,” Murphy said. “But when you are lobbying on social issues, it gets much more complicated. Human nature plays a much greater role.”

Business leaders argue that the outcome of the hate crimes bill is not a failure.

“I think it’s important to note that rarely in any piece of legislation does a group of advocates get exactly what they want,” Fisher said.

O’Connor said the hate crimes bill wasn’t “your typical legislative matter,” so it’s difficult to compare it to a more straightforward business issue.

“We’re sort of comparing the normal process to a not normal subject matter,” O’Connor said.

Smulyan

SmulyanJeff Smulyan, chairman and CEO of Emmis Communications, which was involved with Indiana Forward, said he’s disappointed in the final bill, but he believes the leaders of the coalition did everything they could.

“I don’t think anybody left anything on the field,” Smulyan said. “I think they all did a very, very good job. I don’t know how you’d fault anybody.”

Advocates also argue that it’s likely nothing would have passed the General Assembly if not for their efforts.

“I do think the conversation has been significantly advanced as a result of this process,” said Ann Murtlow, president and CEO of United Way of Central Indiana, a member of the coalition.

The fight lives on

Indiana Forward members promise they won’t stop fighting for a more complete list, but that doesn’t mean they’ll be successful any time soon. Several attempts by Democratic lawmakers this session to amend the list were unsuccessful.

Plus, Republican lawmakers and Holcomb argue changes aren’t necessary.

They say language that covers any characteristic, trait, belief, practice, association or other attribute means it covers everything—including gender identity, gender and age, even though they aren’t in the specific list of traits.

Critics worry, though, that without more specificity, prosecutors will be wary of seeking harsher sentences in those cases.

O’Connor said he knows there might not be much of an appetite for the debate again.

“There will be people who roll their eyes when we say we’re coming back next year,” O’Connor said. “We did make progress. We didn’t make enough progress.”

Downs said the most successful option may be to wait a few years to see if the law works as intended or if it’s not being applied as expected.

That way, there could be data to back up an argument to change it.

But even then, it could be an uphill battle as top lawmakers see this as taken care of.

“I think it’s going to be way too easy for leadership to say, ‘Hey, we dealt with this last year or two years ago’” Downs said. “You’d have to have evidence that will make it a compelling argument.”

Business leaders say the coalition will be patient and stay committed to the issue, even if there isn’t much public attention given to it.

“This is a small step,” Smulyan said. “We have further to go. But you never quit.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.