Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now Hundreds of birds have been killed by hitting windows. The Audubon Society has tracked the species and locations for two years. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)

Hundreds of birds have been killed by hitting windows. The Audubon Society has tracked the species and locations for two years. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)Up, up, into the sky.

Captains of industry build towers so high.

Then, as if lured,

Into the windows slam the sparrow, warbler and ovenbird.

As if predators and starvation weren’t enough of a concern for migrating birds, add in bright city lights.

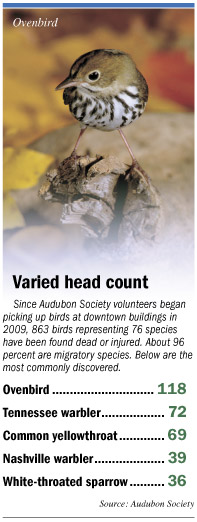

More than 860 such dead-and-injured birds have been tallied downtown by volunteers of the Amos W. Butler Audubon Society since late 2009. That’s in addition to countless others found first by scavengers and building maintenance crews.

Downtown building owners and managers have ruffled feathers at the Audubon Society for not doing more to prevent bird strikes. Migrating birds guided by starlight are sometimes confused by building lights and drop in overnight. When they take to the air after dawn, some fly into windows reflecting sky and vegetation they mistake for the real thing.

“Bright lights in an urban environment confuse the birds … it’s not hard to get distracted by the Chase Tower,” Don Gorney, president of the Amos W. Butler Audubon Society chapter, said of the 830-foot-tall structure that pierces the 500- to-2,000-feet

airspace of migratory birds.

At least Chase Tower managers have agreed to turn off after midnight lights on the tower’s trapezoidal roof—something Gorney and the society’s “Lights Out Indy” program volunteers applaud.

But a few blocks away, the limestone of the Statehouse is irradiated under the glare of dozens of 1,000-watt floodlights angling toward the heavens.

When the Audubon Society asked state officials to have a heart and tone it down, they were told the retina-searing illumination is necessary for security.

Besides, why should the state care, since it is a commercial building across the street that often makes the actual kill? It seems when the birds leave in the morning, they see the sky reflected in the glass walls of Duke Realty Corp.’s 12-story One North Capitol building.

“We find a lot of mostly dead birds at One North Capitol,” Gorney said.

Duke spokeswoman Helen McCarthy said the company makes a concerted effort to turn off its lights—if only for cost savings. “Our concerns are keeping things cleaned up and energy conservation.”

Duke spokeswoman Helen McCarthy said the company makes a concerted effort to turn off its lights—if only for cost savings. “Our concerns are keeping things cleaned up and energy conservation.”

Short of that, there may not be much Duke can do other than spend thousands of dollars to install less-reflecting glass or some other covering to tone down the reflection.

The local Audubon chapter in July 2009 approached the Indianapolis Building Owners and Managers Association, hoping the organization would encourage its members to employ bird-safe practices.

At least three of its e-mails to BOMA board members or officers went unanswered, said Gorney, who kept meticulous records.

That same month, prompted by the Indianapolis Audubon chapter, local BOMA leaders received e-mails from Kent Warden, who heads the BOMA chapter in Minneapolis, suggesting that the Indianapolis chapter get on board.

The building owner chapter there endorsed a Lights Out program by Audubon Minnesota. At least 30 building owners in Minneapolis, St. Paul, Bloomington and Rochester joined the effort.

“The feedback we have gotten is that not only the building managers but the tenants are very enthusiastic about it,” Warden, executive director of Minneapolis’ BOMA chapter, told the Star Tribune in an article about that city’s program.

In his e-mail to Indianapolis BOMA, Warden said he was initially skeptical about the bird strike issue, saying he hadn’t seen evidence of the problem. Minneapolis’ BOMA later voted unanimously to endorse Lights Out after talking with university researchers and Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources.

“It has turned out to be a win-win proposition, with very positive P.R. benefits and energy savings dividends to boot,” Warden wrote to Indianapolis BOMA leaders.

“We found it to be a worthwhile effort and a P.R. bonanza with tenants and the local media, along with energy conservation side benefits … I see no down side in participation in this program, and recommend it without hesitation.”

Two months later, Gorney phoned Boyd Zoccola, who heads the local BOMA board and is an executive of Indianapolis-based real estate firm Hokanson Cos.

Zoccola told Gorney about the problems building managers had with starlings—a nuisance bird with, shall we say, active bowels.

“Although polite, Boyd was not interested in pursuing collaboration with Amos W. Butler Audubon on Lights Out Indy,” Gorney said. “We were somewhat surprised by that because BOMA is a strong partner in other cities.”

Zoccola said he polled the BOMA Indianapolis board after the call “and not one of our board members at the time had any experience with dead birds at their buildings. … Our biggest problem is with starlings and pigeons and droppings around buildings.”

Building owners have had their hands full cleaning up after nuisance birds to avoid legal liabilities. Bird droppings can spread diseases such as histoplasmosis and otherwise damage buildings with their corrosive droppings.

The most common question, Zoccola added, was what impact would lights on—or off—have on “our more pressing bird issues. Many of our buildings have already shed exterior lighting for energy purposes, with the exception of game nights or significant downtown events.”

Gorney said turning off lights might actually reduce the starling problem building owners worry about, as those same lights also draw nuisance birds as a source of heat in cold weather.

The birds that bonk their heads into the afterlife on downtown buildings aren’t generally the nuisance variety that plague building owners, like starlings and pigeons.

Rather, the vast majority are native songbirds.

Of the 863 dead and injured birds observed by Audubon volunteers in 2009-2010, 56 percent were warblers. Among the other 76 species were ovenbirds, the common yellowthroat and white-throated sparrow.

Some of the dead birds are collected by Audubon volunteers and donated to the Indiana State Museum, and to various wildlife centers for research purposes.

Dangerous migration

Many native species will be on the move soon, as September is peak migratory season.

The biggest threat along the way appears to be humans. Buildings cause 58 percent of bird deaths, compared with 11 percent caused by cats and less than 1 percent by wind turbines, according U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

Other downtown Indianapolis building owners and managers, in addition to those of Chase Tower, have been receptive to working with Audubon to find ways to reduce strikes. One is the Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library, whose expansive glass-covered Central Library addition downtown has been the site of 266 recorded bird kills.

Bird advocates are asking building owners to take steps such as turning out lights earlier, using blinds and putting film on windows to curtail deaths. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)

Bird advocates are asking building owners to take steps such as turning out lights earlier, using blinds and putting film on windows to curtail deaths. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)Recently, though, the number is down somewhat, said Mike Coghlan, the library’s capital projects manager.

“I know we had less strikes and fatalities than we had in previous years … [Last fall], we worked on our lighting strategy so the building was darker.”

One possible solution, which is part of the library’s energy-saving goal, is to more actively use blinds on the south side of the building to reduce air-conditioning usage.

Certain kinds of blinds can also help birds distinguish a building from the actual sky, particularly in buildings like the library where one can almost see through to the other side.

The library initially planned to coordinate lowering of its powered blinds with a computer. That was scratched when construction costs rose, and blinds motors were instead triggered by light sensors. A computer might do a better job, but wiring everything up on the building could cost a prohibitive $25,000.

The north-facing side of the building doesn’t need sunshades and doesn’t have them.

Another major building owner partnering with Audubon is the city of Indianapolis. The City-County Building has long had a screen-like treatment on its windows that makes them less reflective. But to save electricity and make the building less of a magnet for birds, cleaning crews start on upper floors at night and work their way down, said John Hazlett, director of the city’s Office of Sustainability.

“They turn out the lights as they leave a floor. So those birds aren’t attracted to the light patterns.”

Gorney said it may be practical in some buildings to add such things as window films with patterns birds can see—at least in areas of the building where most bird strikes occur.

If buildings must be lit up at night, the group suggests techniques such as down-facing lighting, rather than upward-shining lighting that acts as more of a bird beacon.

Friendly design

Some newer buildings have been designed with bird-friendly features, such as the Indiana State Museum, which Audubon praises for installing fritted glass on a skywalk. IUPUI, meanwhile, has placed a film wrap on some of its skywalks. The wraps serve a marketing purpose, but they’re also highly visible to feathered friends.

OneAmerica Tower has trees that block birds from striking windows on the first couple of floors, where many strikes tend to occur.

OneAmerica Tower has trees that block birds from striking windows on the first couple of floors, where many strikes tend to occur.

Curiously, many of the so-called green building designs of recent years aren’t necessarily bird-friendly. Many make extensive use of glass curtain walls and atriums designed to enhance natural lighting and lower electric lighting bills.

They’re often highly reflective and sometimes allow birds to see through a building, as if there were nothing there.

“My guess is, it’s sort of, ‘Oh, we didn’t think of that sort of thing,’” said Mac Williams, CEO of Indianapolis-based Inverde Design, an architectural firm known for environmentally friendly designs.

He noted that a number of cities—Chicago and San Francisco among them—have begun incorporating into building codes guidance on how to make buildings safer for birds.

Some manufacturers have already come up with windows, sold under brand names such as Ornilux, containing features visible to birds but undetectable to the human eye.

Meanwhile, the American Bird Conservancy has proposed legislation that would require bird-friendly design features be adopted in federal building projects. ABC has also been working with the U.S. Green Building Council, which created the LEED environmental certification program, to establish a credit for bird-friendly design in LEED 2012.

Audubon’s Lights Out Indy program has gotten a lift, lately. It will be among several local community organizations to share a $69,850 U.S. Fish and Wildlife grant to help conserve migratory birds.

Gorney hopes to be able to at least hire a part-time employee toward Lights Out Indy. “It’s a largely volunteer effort, so it has been difficult.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.