Subscriber Benefit

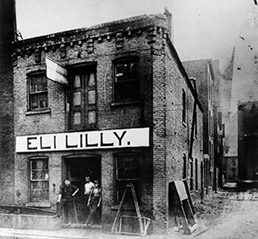

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowCol. Eli Lilly opened his first pharmaceutical research lab in a two-story brick building in the heart of downtown Indianapolis in 1876.

Barely a decade later, Eli Lilly and Co. had grown from three employees to more than 100 and needed room to expand, so the company moved to a new facility on McCarty Street.

Over the next 100 years, the company swallowed up surrounding homes, warehouses and produce markets to make way for a world-class corporate campus on a rectangle bordered by South, Delaware and East streets and Interstate 70. And the company didn’t stop there, acquiring adjacent properties as they became available and growing into the newly renovated $58 million Faris Campus a block to the west in 2002.

But in recent years, Lilly’s business model and approach to growth have evolved. Whereas everyone down to the janitor was once a Lilly employee, today, most positions that aren’t central to the research mission are filled by independent contractors, reducing the need for headquarters office space. And when the company makes an acquisition, such as its $6.5 billion deal in 2008 for New Jersey-based ImClone Systems, it tries to retain the culture of the acquisition target rather than moving employees en masseto Indianapolis.

While the changes to Indianapolis’ largest employer have put city leaders on edge, the moves aren’t all bad news for downtown: As Lilly retreats into its 120-acre campus, it is making moves with surplus real estate that could establish the strongest physical connection between Lilly and downtown since the company was founded at Pearl and Meridian streets at a time when the Circle was still home to the Governor’s Mansion and not the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument.

Lilly is negotiating with British aerospace firm Rolls-Royce Corp. to sublease the 480,000-square-foot Faris Campus for as many as 2,500 employees. And Lilly has partnered with local developer Buckingham Cos. on a $155 million mixed-use project called North of South that would replace 10 acres of Lilly parking lots near Delaware and South streets.

North of South would add a hotel, a YMCA branch and more than 300 apartment units. Lilly tore down an old Indianapolis Star warehouse it uses for storage to replace some of the parking it will lose in the deal.

Room to expand

The North of South mixed-use development is expected to bridge Lilly’s corporate campus and the rest of downtown. (Rendering courtesy Buckingham Cos.)Lilly has plenty of room on the existing corporate campus for “whatever our needs might be in the future”—meaning Lilly can offer surplus parcels for projects complementing both its own corporate campus and the city, said Steve Van Soelen, Lilly’s manager of real estate and strategic facilities planning.

“Over the years, as the city has developed, it has developed to Lilly,” Van Soelen said. “The [North of South] parcel is kind of that connection point.”

It’s also a potential recruitment tool for Lilly to attract employees who otherwise would look for work in major coastal cities. Working in or near a city is high on the list of desirables for many of the company’s roughly 8,900 local employees, 7,000 of whom work at the McCarty Street campus.

Recruits will find a new workplace model that isn’t the traditional “Dilbert cube-land,” Van Soelen said.

The North of South mixed-use development is expected to bridge Lilly’s corporate campus and the rest of downtown. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)

The North of South mixed-use development is expected to bridge Lilly’s corporate campus and the rest of downtown. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)“We’re creating places where people can bump into people like molecules, allowing collaboration to happen,” he said.

It isn’t a cheap transition for Lilly: The company has spent $2 billion in recent years to repurpose existing buildings and build new ones in Indianapolis, including at its massive production facilities on Kentucky Avenue.

The company is Marion County’s largest taxpayer and its largest property owner by assessed value, by a margin of almost $1 billion over No. 2 property owner Indianapolis Power & Light Co.

Downtown evolution

The initial trajectory for the growth of downtown Indianapolis was to the north, but the completion of Circle Centre mall in 1995 helped redirect focus to the south. The construction of WellPoint Inc.’s Blue Cross Blue Shield operations center in the late 1990s on what had been Lilly-owned property, and the completion of Lucas Oil Stadium a decade later provided even more momentum.

“To me, there’s just a natural evolution for the growth of the downtown area to move toward those employment centers,” said Abbe Hohmann, chairwoman of the Indianapolis-Marion County Building Authority and a principal in the local office of Cassidy Turley.

North of South came together because Lilly had property it no longer needed for expansion, and the company saw it as an opportunity to create a downtown amenity benefiting both the city and its employees, Hohmann said.

Lilly CEO John Lechleiter, who lives downtown, advocated for the project and supported teaming up with Buckingham.

“We could’ve done a national beauty contest, but it was important to work with someone who is invested with the community,” Van Soelen said. “It was important to marry Indianapolis companies.”

A future phase of the Cultural Trail should help complete the connection between downtown and the southeast quadrant, an area that will have more than 15,000 employees if Rolls-Royce joins the party at the Faris Campus. (WellPoint adds about 2,500 and Farm Bureau, with headquarters on East Street, has about 1,500.)

A future phase of the Cultural Trail should help complete the connection between downtown and the southeast quadrant, an area that will have more than 15,000 employees if Rolls-Royce joins the party at the Faris Campus. (WellPoint adds about 2,500 and Farm Bureau, with headquarters on East Street, has about 1,500.)

If North of South succeeds in replacing acres of surface parking lots and other pending deals materialize, all of downtown should benefit, said Deputy Mayor Michael Huber.

“They approached the city because they want to create a more significant connection between the Lilly campus and downtown,” Huber said.

Opening doors

The goal of building connectivity is an admirable one in a city where the “mini-campus” has been a favorite development pattern both for corporations like Lilly and Anthem and public entities like IUPUI and state government for years, said Aaron Renn, a consultant on urban planning and author of the Urbanophile blog.

Most of the “self-contained little worlds”—which tend to offer dining, banking and child-care services without leaving the friendly confines—were built before the downtown core began to bounce back from years of decline, and were designed in part to create a sense of safety.

The city’s flat topography also encouraged spread-out developments.

“It would be better if we could figure out how to create more integrated districts,” Renn said. “Now that we have a downtown that’s much more thriving, you want to open your doors and engage because what’s outside your doors is now much more attractive.”

‘Safe, clean, convenient’

Lilly for years focused on developing amenities for employees within or near its corporate campus, including on-site cafeterias, a day care center and the Eli Lilly Federal Credit Union.

Lilly assembled a sprawling collection of real estate after Col. Eli Lilly launched his drug company in a modest, two-story building at Meridian and Pearl streets in 1876. (Indiana Historical Society, Eli Lilly and Co.)

Lilly assembled a sprawling collection of real estate after Col. Eli Lilly launched his drug company in a modest, two-story building at Meridian and Pearl streets in 1876. (Indiana Historical Society, Eli Lilly and Co.)Acquiring properties as they came available, including the former homes of Klemm’s Meat Market and Indiana Fan & Fabrication and a wholesale flower market, gave Lilly flexibility to add to its campus and provide services to its employees. Many of the properties remained in reserve for years.

“We wanted it to be a safe, clean, convenient place to work,” said John G. Leicht, Lilly’s former head of real estate who retired in 2003 and now runs the energy and building operations consulting firm Edward George & Associates.

“Over a number of years when I was there, Lilly acquired individual parcels as they became available and worked to complete a chunk of land that could be all Lilly and could be secured and provide parking,” Leicht said.

The company last year bought and tore down the last single-family home within its corporate footprint—a two-story at the southwest corner of Henry and Alabama streets occupied until her death by a woman who simply didn’t want to sell. She may have been surrounded by parking lots, but she did have Lilly’s security detail to look after her.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.