Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now Brian Payne wants to talk about racism. And how it’s holding central Indiana back.

Brian Payne wants to talk about racism. And how it’s holding central Indiana back.

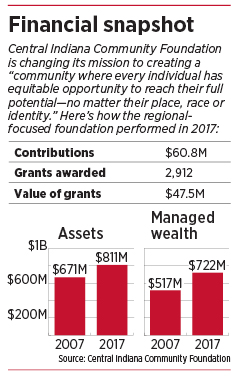

Under his leadership, the Central Indiana Community Foundation—which controls more than $800 million in charitable assets and helps direct the gifts from wealthy donors—is undergoing a transformation aimed at narrowing the growing gulf between the community’s affluent and poor.

“We can’t shy away from racism,” said Payne, 59. “We’ve got to tackle that head on. America has done a horrible job of confronting its racist past. I would say Indianapolis has done a horrible job, too. We need to do a lot better.”

Payne

PayneRace and the economy are intertwined. Black Americans have substantially lower rates of upward mobility than whites, according to new Stanford University research, leading to income disparities that ability differences do not explain. Even black boys who grow up in the same neighborhood as white boys have lower incomes in adulthood in 99 percent of U.S. Census tracts.

In Indianapolis, the white unemployment rate is 10 percentage points lower than the black unemployment rate of 16.3 percent, according to 2016 U.S. Census statistics, even though the labor force participation rate of the two groups is the same.

The philanthropy group in March changed its mission, which previously was “to inspire, support and practice philanthropy, leadership and service in our community.”

Now, CICF wants to help residents “reach their full potential—no matter their place, race or identity,” primarily by “empowering people, changing unfair systems, and dismantling institutional racism.”

The 41-employee organization also has made several operational changes in recent months—from small moves like seeking out caterers run by minorities when it hosts events to structural shifts that will affect which programs and initiatives it decides to fund.

Toward that end, Payne in April promoted CICF’s Pamela Ross, 53, who came to the organization two years ago after a career in social work and child services, to a new position: vice president of opportunity, equity and inclusion. Among other duties, Ross is charged with helping change the culture within CICF to focus on “equity and anti-racism.”

CICF’s entire staff has undergone “Undoing Racism” training, an intensive two-day program that talks about the history of institutionalized racism in the country. The organization also is funding an effort to provide that training to more businesses and groups in Indianapolis.

In addition, the group in 2017 launched an ambassador program featuring 36 diverse residents from neighborhoods in Marion and Hamilton counties who have been meeting with and capturing the ideas and challenges of residents who sometimes don’t have a voice in community development work.

Beatrice Beverly, who helps run Stop the Violence Indianapolis and is a CICF neighborhood ambassador for Martindale-Brightwood, said the work has reconnected her with the neighborhood she grew up in, but felt increasingly disconnected from. She said she now feels more accountable to the residents.

“I had forgotten the zoo was in Washington Park,” Beverly said. “I had forgotten about Richard’s Market Basket at 35th and Sherman. I had that a-ha moment. I had forgotten that rich history.”

Beverly

BeverlyAs part of its revised mission, CICF is developing a new strategy that it will unveil in the first quarter of next year. Nothing has been finalized, but Ross said CICF is discussing focusing on transportation, mass incarceration, offender re-entry and workforce development.

The shift

CICF’s stakeholders are noticing the changes.

Mark Russell, director of education and family services at the Indianapolis Urban League, said it’s “extremely unusual in Indianapolis to see a major community institution that is not black-led to talk about the realities of systemic and structural racism.”

“This is a radical departure from past practice,” Russell said. “That’s real work.”

CICF leaders say they don’t want to just give lip service to promoting diversity. They want to create real change—while recognizing how entrenched some of the challenges are.

“This is not a project for me. This is my life. This is the life of people I know. This is what I’ve known. We can’t get in and get out,” Ross said.

“There has to be a real sense of humbleness and genuineness. Are we placing ourselves in a place to learn versus act? If you’re a powerful institution with assets, that’s what you’re used to doing. You hear about something and try to fix it. We’ve got to learn and then figure out what to do to fix it.”

Russell

RussellCICF doles out about $7 million a year from its $140 million Indianapolis Fund. In the past, about 70 percent went toward making Indianapolis an attractive city for young professionals, and 30 percent went toward neighborhoods that needed a boost.

“We’re flipping the balance,” Payne said. “For the next five to 10 years, we’re going to be 70 percent working in neighborhoods that need investment and 30 percent on attracting and retaining young professionals.”

Payne said CICF will encourage groups who cease to be funded to “make an adaptation to become more inclusive” or provide services in a way that’s “asking what neighborhoods and people need instead of selling them what you created.”

CICF Board Chairman Gregory Hahn, a partner at Bose McKinney & Evans LLP, said he is under no illusions progress will come easily—and he knows the group could face pushback along the way.

“It will be hard,” Hahn said. “But we all felt like it’s something we needed to try. Whatever progress we make is better than where we were before.”

Payne said most of the individuals and organizations CICF has told about its mission change have been supportive. He said his group’s plans continue to evolve based on the feedback they’re receiving.

But he is not ruling out the possibility that some people will be turned off by the new vision—a reality he accepts.

“I have had conversations where people … just don’t think there is institutional racism existing, or that people’s challenges really have nothing to do with race,” Payne said. “We know the data says something else—that race is a major barrier in this country.”

Payne predicted that perhaps 60 percent “of our current or potential stakeholders will want to be part of it because we can create a convincing economic, moral and societal argument.”

Perhaps 20 percent to 30 percent will “need time to process to be engaged,” he said, and an even smaller group will say, “‘I was going to put my money in but now I’m not.’”

“I’m very OK with those numbers,” Payne said.

‘Awareness is a powerful thing’

Payne said confronting racism is difficult. It’s a journey he has taken himself in the last few years.

He said he has studied the work of Harvard University economics professor Raj Chetty—one of the authors of the research on racial income disparities—and others. That’s led to some disturbing conclusions and realizations about his own city—and the way business has been conducted here.

One of Chetty’s recent studies found that, if you grew up in Indianapolis and started from the bottom fifth of the economy, you had just a 4.9 percent chance of ever reaching the top fifth. That makes Indianapolis one of the least-mobile cities in the nation.

One of Chetty’s recent studies found that, if you grew up in Indianapolis and started from the bottom fifth of the economy, you had just a 4.9 percent chance of ever reaching the top fifth. That makes Indianapolis one of the least-mobile cities in the nation.

Payne has thought about the creation of Unigov in the 1960s, which merged city and county governments in Marion County but excluded the school districts. He’s recognized “how there was racism involved in that decision.”

He’s thought about the city’s debates over transportation and some north-side residents’ vocal opposition to building the Red Line bus rapid transit network from Broad Ripple to the University of Indianapolis, and how “some white people don’t want black people or Latino people to have access to their pristine neighborhoods via bus.”

He’s thought about the ongoing fight over the Indiana Department of Transportation’s proposal to rebuild the I-65/I-70 north split, rather than pursue more neighborhood-friendly alternatives. At one point in the debate, he said, he recognized that the people at the table with the loudest voices were white and wealthy.

“There was maybe a moment where it looked like we could broker something for the north side” that would have come at the expense of the east side, he said, but he knew it wasn’t right to have “white people getting what they need at the expense of potentially black and Latino neighborhoods.”

“I think that’s progress, that we caught ourselves at a potentially key moment,” Payne said. “This awareness is a powerful thing. I catch myself all the time, to say, ‘Oh, I would not have thought that way.’ I see things differently.”

Calculated decision

He said the Undoing Racism workshops that he participated in struck him emotionally.

“Everybody was kind of freaked out,” Payne said. “We’ve got this new knowledge about how racism has been institutionalized since the beginning of America. I came out personally mad about a lot of things. How could I go to a good high school, take American history, go to college, take American history, and not learn any of this? I felt like I wanted a refund.”

CICF leaders initially were reluctant to address racism head on and instead wanted to frame the shift in mission primarily around opportunity. But committed staff members ultimately convinced leadership.

“CICF has not made this decision overnight,” said Board Vice Chairman Aasif Bade, president of Ambrose Property Group. “It’s been a very calculated, collaborative decision with board members and staff members really pushing to reach for this change and encouraging the leadership and the board to do this. Even in the next few years, I think it can be transformational.”

He said it helps that other local organizations—including the Indy Chamber—are also stepping up the push for “inclusive growth.” The effort, which includes the neighborhood development group Local Initiatives Support Corp. and the Central Indiana Corporate Partnership, is driven by the reality that many Indianapolis residents have been left behind in the economic resurgence.

While the city’s tech sector has boomed, and some neighborhoods are thriving, median household incomes have dropped in a full third of Indianapolis ZIP codes since 2000, IBJ reported this spring.

“The data shows there is this problem that’s getting worse and many, many people are understanding we need to do something different,” Payne said. “We can still course-correct.”

‘A sense of hope’

Mason

MasonObservers of CICF’s new mission hope its impact will be far-reaching.

“Foundations are very important gatekeepers,” said Cindy Booth, executive director of Child Advocates, which is convening Undoing Racism sessions partially funded by CICF. “Anyone who works in a not-for-profit knows that.”

Booth said “it’s commendable they recognize the power they have in the community, being willing to look in an earnest and thoughtful way about what institutional racism is doing in our community.”

“It is painful; it is thought-provoking and challenging,” Booth said. “But it is doable.”

Tony Mason, CEO of the Indianapolis Urban League, said organizations like his have often found themselves being “a voice for the voiceless” on issues like racism.

“To see an organization like CICF step forward to take on this challenge for us was inspiring in creating a sense of hope,” Mason said. “To know CICF wants to lead, support and partner to address systemic racism is important. I’m excited about the work CICF wants to do in this space.”

He encouraged other businesses and funders to get involved and work together, and not be held back by “being really, really uncomfortable about confronting our challenges.”

Schnable

SchnableAllison Schnable, an assistant professor focusing on philanthropy at Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs, said CICF “is in a position to lead” in a convening role, an effort that has the potential to reverberate across the region.

“The potential of including that in their mission is about looking at racism as something more than individual bias,” Schnable said.

“We can build systems that make institutional racism worse. It can have these unintended effects. Pushing funders and partners to think about that—that’s the potential.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.