Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowSince Indianapolis started courting major sporting events back in the 1980s, it has relied on the corporate community and foundations to help foot the bill.

Eli Lilly and Co., the Indianapolis Colts, Duke Energy Corp., Anthem Inc. and so many others have pitched in for the pursuit of everything from NCAA championships to the Super Bowl.

The theory is that, in exchange for the upfront monetary investment, the city receives a payback that includes a wave of free-spending visitors and copious national publicity.

“While it may cost a city several million dollars to win a major sports tournament, the economic impact for the local community and state is multiplied, many would say by as much as six times the investment,” said Sherri Middleton, executive editor of the trade publication SportsEvents Magazine. “Though, the exact details of these major sports-hosting deals are never truly known because of all of the moving parts that go into the bid package.”

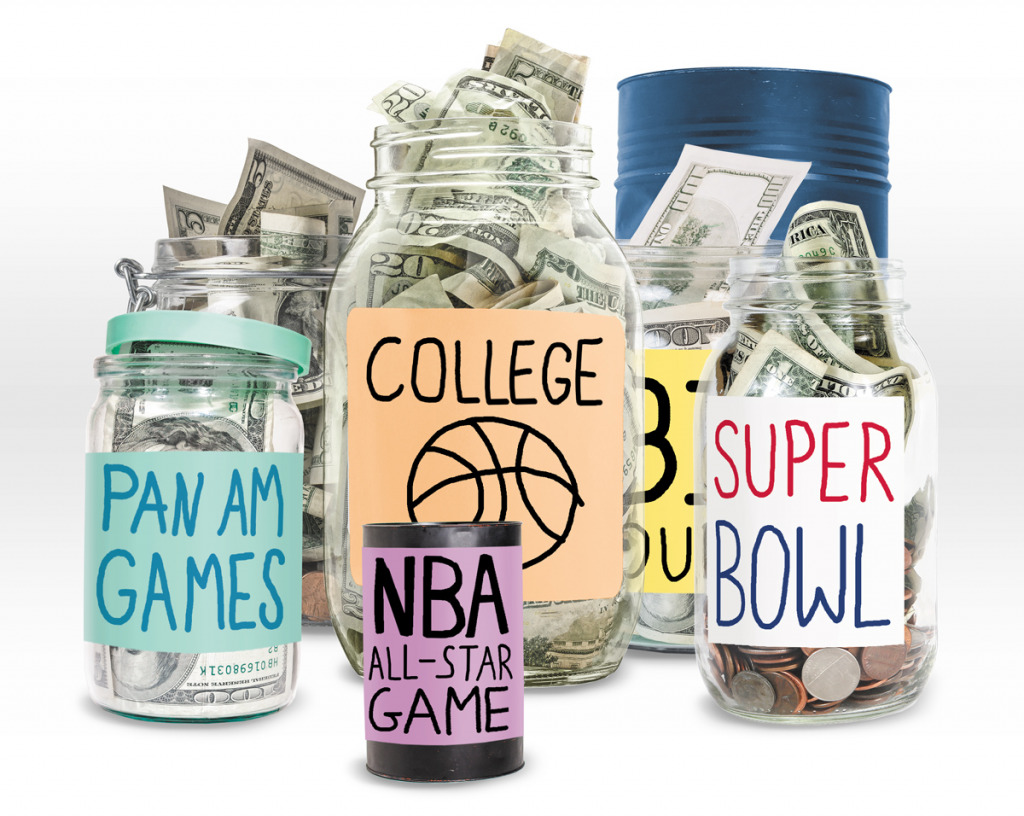

The Indiana Sports Corp. created the Indy Championships Fund in 2017 to raise $26 million to help fund three events:

◗ the 2021 NBA All-Star Game, which was postponed to 2024;

◗ the NCAA Men’s Basketball Final Four, which is now the entire tournament; and

◗ the College Football Playoff National Championship, scheduled for next year.

So far, it has raised $23 million, 88% of the goal.

But what’s in it for the individual organizations that donate money to the Indy Championships Fund or similar efforts?

Well, civic pride more than anything else.

Companies don’t see their name slathered across banners, or get a truckload of tickets to the actual event. Instead, they’re rewarded with event swag; tickets to ancillary, city-arranged events their cash helped finance; and the opportunity for their employees to serve as volunteers at various venues.

Companies don’t see their name slathered across banners, or get a truckload of tickets to the actual event. Instead, they’re rewarded with event swag; tickets to ancillary, city-arranged events their cash helped finance; and the opportunity for their employees to serve as volunteers at various venues.

(Of course, that’s what happens in a typical year. There are far fewer of those opportunities for the ongoing NCAA Tournament.)

OneAmerica is among the companies that donates regularly to help the Indiana Sports Corp. with bids as well as with the organization of major events. The company’s leaders see the money as investments in the city’s success overall—and when the city is successful, the companies located here can be successful, as well, said Lou Ann Baker, OneAmerica’s public relations director.

“It’s all about having pride in Indianapolis. It’s about continuing that vibrancy,” she said. “It’s sharing with the rest of the world what we know about our city.”

No downside

That can play out in many ways. Among them: talent attraction—which could be especially important as more companies allow employees to work remotely and, thus, live anyplace they want.

“Because we’re not on the coasts … people may not know we have so much to offer,” Baker said. But high-profile sports events “give us an opportunity to shine.”

Allison Melangton, CEO of the 2012 Super Bowl Host Committee and former Sports Corp. president, said the former CEO of Lilly once told her that talent recruitment was one of the most important reasons for the city to host big events.

“We were on a global stage with other global cities, and he had an easier time recruiting scientists and attracting people to Indianapolis because we were viewed as highly successful and very engaged,” she said. “So … they help fund all these city events so that we can help them attract people to the Midwest from the coasts.”

Shiel Sexton is another company that has donated to funds that attracted the Super Bowl in 2012 and numerous Big Ten championships and Final Fours.

CEO Kevin Hunt said the investments this year are aimed at helping the city recover from the pandemic. But he acknowledged it can be harder to see direct benefits to his company.

“You might not see any return right away,” Hunt said. “No one at the championship game is going to hire us or seek out our website or look to see who we are. It’s not like [when] somebody puts up a Coke or Pepsi sign and people think, ‘Oh, I’m going to have one.’ We’re a construction company, and that’s not an impulse purchase.”

That’s not to say the company’s civic participation won’t be noted by the sorts of folks who order multimillion-dollar construction gigs. Given that, there’s really no downside to associating your company with a hugely successful local event. “We did pre-pandemic renovations on the JW Marriott last year,” Hunt said. “And now that’s where the tournament teams are.”

‘A huge selling point’

Typically, Indianapolis no longer has to demonstrate upfront where the cash to hold up its portion of the deal will come from. This isn’t the city’s first rodeo, so national organizing bodies know the Indiana Sports Corp. is good for it.

But in one case, snagging all those cash commitments early turned out to be extremely helpful. During its ultimately failed effort to win the 2011 Super Bowl, the Indiana Sports Corp. lined up all the funds necessary to pay for its part of the program. When the city put together its winning bid for the 2012 game, it did so with all those commitments still in place—something no other bidder could offer.

“That was a huge selling point,” Williams said. “Nobody had ever done that. That’s the thing in Indianapolis. We always have something in our hip pocket that blows them away.”

“The Super Bowl was an interesting test of trust, because, when we went out to raise the money, it was before we knew what benefits the donors got,” Melangton said. “So we raised money without guaranteeing benefits. That was highly unusual, but because we were raising it before the bid, that’s the way we had to do it.”

But while Indy boasts a cadre of local businesses and charitable entities that have helped finance sporting events for decades, the local pool is much shallower than in such potential competitors as Minneapolis, home to deep-pocketed firms like Target and 3M.

“These companies are based there, and have been there forever,” Williams said. “So, raising money might not be the problem. But [pulling off the event] could be the problem.”

In other words, while Indianapolis might not have the fattest wallet, it’s been perfectly adequate to finance the city’s responsibilities for everything from the 1987 Pan American Games to the Super Bowl. And the city has proven again and again that it has the experience, human capital and infrastructure to make things happen.

“There’s no misunderstanding about why the NCAA is doing what it’s doing in Indianapolis,” Williams said. “It’s because of what we’ve done historically. They don’t believe they could have done this anywhere else, in my opinion. Because there’s a long history here of success and exceeding expectations.”

Three in 11 months

It’s worth noting, however, that the city’s commitment to three major events in 11 months was a financial and logistical challenge on a level it had not seen since it staged the Pan Am Games.

“So, we [started] the Indy Championships Fund to take a singular focus on funding the roughly $26 million budget that we would need to deliver these events within that very tight window,” said David Lewis, president of the Indy Championship Fund.

Think of it as a United Way for sports, with local entities donating money not to a particular event, but to help finance the city’s commitments to all three. Lewis has worked on large-scale community fundraising projects before, but nothing quite like this. “To my knowledge, no city has delivered three such events within 11 months,” he said.

The idea was to free up individual event planners from their tin-cup duties, and also to avoid approaching local businesses three separate times for donations.

Interestingly, of the three events, the one that’s getting the least funding attention is the 2021 Final Four. That’s because the added expenses of moving the entire tournament to Indy, announced only 10 weeks ago, are mostly being covered by other entities, such as the NCAA.

However, the ICF stands by to help out as needed and has already chipped in on one high-profile project.

“One of the things we wanted to do for the city was the bracket on the side of the JW Marriott,” Lewis said. “The ICF did participate in the funding of that because we viewed it as a critically important way to portray an innovative city to the country and the world as they watched the tournament.”

Staying the course

The championship fund secured many of its donations before the pandemic began. The approximately 50 businesses and individuals who signed on pre-COVID have stuck to their commitments, regardless of the economic problems they’ve faced.

“Not one has asked to be relieved of the pledges they made,” Lewis said. “We schedule payments to make it easy for businesses to manage their cash flow. You might make one in 2018, then 2019 and 2020. And not one single company has failed to make their scheduled payments.”

That roster of companies, individuals and foundations includes the Lilly Foundation, Eli Lilly and Co., the Indianapolis Colts, the Indiana Pacers, Duke Energy and Salesforce.

One attraction for those big companies, Williams said, is the opportunity to put their employees into volunteer positions for the events.

“That ability to participate in city sporting events is seen as a talent-retainment issue by these big companies,” she said. “This year, the volunteers are actually doing laundry for coaches and the teams.”

It’s a measure of the city’s interest in massive sporting events that armies of volunteers can be assembled for such tasks—and that companies can see having their employees spend a weekend washing smelly uniforms as a perk. But the tradition goes back a long way. Hunt remembers personally picking up trash at the Super Bowl Village, while dozens of Shiel Sexton employees helped with everything from running the zip line to providing information to out-of-towners.

“When I was emptying people’s beer bottles during the Super Bowl, I didn’t at the time think of it as a perk,” he said. “But it was a good time. We probably had 50 employees volunteering for different things during the Super Bowl.”

And Baker said she volunteered for the 1987 Pan Am Games shortly after moving to Indianapolis, an experience that stayed with her as she moved into roles in public service and with private companies.

“I think those early experiences should never be underestimated for the pride and the excitement and enthusiasm that people have, not just for the event,” she said, “but that they develop for the city.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.