Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIt didn’t happen overnight, but the number of wine wholesalers in Indiana has dwindled from hundreds to only a couple of dozen.

That consolidation has raised concerns for small wineries that might not produce enough wine to attract a major distributor. It’s a catch-22 of sorts: Wineries need distributors to grow, but they can’t get the distributor’s attention unless they are big enough. And fewer distributors means fewer options for all wineries.

Under the three-tier alcohol system the state set up after Prohibition, alcohol producers such as wineries, breweries and distilleries cannot sell their products directly to retailers and restaurants. Instead, they must distribute them through a wholesaler.

Until recently, two dozen of Indiana’s small wineries distributed through Indianapolis-based Monarch Beverage Co., which started working with them about four years ago.

Terry

Terry“We’re both Hoosier companies,” Monarch CEO Phil Terry said of each of the small wineries. “Let’s figure out how we can grow together.”

But Monarch closed its wine distribution division on Sept. 1 after losing a years-long battle with the state to be granted permission to distribute liquor in addition to beer and wine.

Monarch intensely pursued the liquor distribution license—which by state law cannot be given to an entity that also has a beer distribution permit—so it could keep its biggest wine customer, E. & J. Gallo Winery. California-based Gallo has been producing liquor for 10 years and, until last year, continued to work with Monarch on its wine sales, even as it worked with other distributors on its liquor sales. It was waiting to see whether the company would eventually win the right to distribute Gallo’s liquor products, too.

But lawmakers turned Monarch down year after year, and Terry had similarly bad luck pursuing the option through the courts.

“Finally, I had to tell [Gallo] last year that I’m out of tricks,” he said. “I’ve got nothing else up my sleeve on this one.”

When Gallo ended its relationship with Monarch, the distributor dropped wine distribution altogether and laid off 100 employees.

“That ended up being 20 percent of our bottom line that went away,” Terry said.

“That ended up being 20 percent of our bottom line that went away,” Terry said.

St. Paul, Minnesota-based Johnson Brothers Liquor Co. has picked up most of Monarch’s wine business, including the small wineries, but the transition wasn’t smooth and some winery owners fear being dropped by Johnson.

“They could decide at any time that our business is not worth the headache and the paperwork and then our hands would be tied,” said Deb Miller, who owns Blackhawk Winery in Sheridan with her husband, John. “Honestly, I don’t think Johnson Brothers would talk to us if we hadn’t had the historic relationship with Monarch.”

Jim Howard, president of Johnson Brothers Indiana, said in a statement the company “is committed to maintaining a relationship with small wineries as well as the expansion and growth of our Indiana wines portfolio.”

“We currently represent a number of Indiana wineries and we have a sales manager dedicated exclusively to the marketing and sale of Indiana wines,” Howard said.

Access and encroachment

Still, some of the small wineries that previously worked with Monarch are lobbying lawmakers to gain easier access to a permit that would allow them to self-distribute up to 12,000 gallons of wine annually.

“For a lot of wineries, that’s our primary issue this session,” said Jim Butler, owner of Bloomington-based Butler Winery and treasurer of the Indiana Winery & Vineyard Association.

The so-called “micro-wholesaler permit” has actually existed about 12 years. But state law does not allow common ownership of both the permit and a winery. Some family-owned wineries get around that by having different family members own the winery permit and the wholesale permit.

But not every small winery has another family member or other partner who can put the permit in his or her name.

The situation can be a headache even for larger wineries. As the older generation thinks about retirement and handing down the businesses, families have to deal with separate companies owning the permits and the wineries.

Clere

ClereSo Republican Rep. Ed Clere, R-New Albany, has introduced legislation that would allow for common ownership of the permit and a winery. Clere said he’s trying to make it easier for wineries to grow their business.

“There’s no good reason for the separate ownership other than creating a barrier,” he said.

Out-of-state alcohol distributors have been encroaching on Indiana for decades, but recent acquisitions and mergers among national players have made the wine wholesale field even smaller.

In late 2009, Miami-based Southern Wine & Spirits received approval to begin doing business in the state, despite initial opposition from the Indiana Alcohol and Tobacco Commission.

Indianapolis-based National Wine & Spirits Inc. officials had argued against allowing Southern to distribute in Indiana, saying the company would take some of their business. National Wine & Spirits pointed to Southern’s proposed merged with Dallas-based Glazer’s Distributors as proof that the Miami company would dominate the market.

Plus, Glazer’s already owned 50 percent of Indianapolis-based Olinger Distributing Co.

But the ATC gave Southern the permit after the distributor announced that its merger with Glazer’s had been canceled.

Only a few months after that, Dallas-based Republic National Distributing Co., which had already been growing through a series of mergers and acquisitions, acquired National Wine & Spirits.

Later in 2010, Glazer’s bought the remaining 50 percent of Olinger, completing that acquisition.

And in 2016, Southern and Glazer’s did end up merging, to become Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits LLC.

In the hands of a few

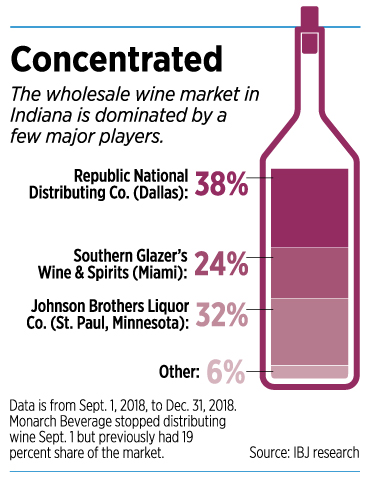

With Monarch now out of the wine business, about 94 percent of Indiana’s wine distribution is controlled by three out-of-state operations: Johnson Brothers, Southern Glazer’s and Republic National, according to excise tax data. Previously, Monarch had about 19 percent of the market, and its share mostly went to Johnson Brothers.

“The point is that we’ve gotten very consolidated at the wholesale tier and, unfortunately, it’s with out-of-state folks,” Terry said. “I just think, ‘Boy—is this really a good deal for the state and the retailers and the Indiana wineries?’ I don’t think so. But it is what it is.”

Purucker

PuruckerJim Purucker, executive director of Wine & Spirits Wholesalers of Indiana, said Republic National and Southern Glazer’s, which are represented by his organization, have not seen an increase in demand since Monarch left the wine business.

“Monarch chose to get out of the wine business. They didn’t have to,” Purucker said. “For them to suggest that they’re a victim in this is a little insincere.”

Purucker said the wholesalers he represents are not opposed to working with small wineries.

“The business has to make sense,” he said. “There has to be a good fit.”

Some of Indiana’s small wineries would like to build their business without having to attract a large distributor.

That could mean being able to put bottles on the shelf of a local liquor store or to be featured on a local restaurant menu—small steps that the wineries argue help them grow to a point where they can distribute significant amounts and would work with a wholesaler.

“Nobody is going to put you in a store if they don’t know who you are,” Miller said.

A few smaller wholesalers do operate in the state, but working with those companies can have its downsides, Butler said.

For example, restaurants and retailers don’t always work with every distributor, so if the wholesaler doesn’t have a relationship with the businesses a winery is trying to get their products into, it could still be stuck.

Butler said he also experienced a small wholesaler not paying him and has heard stories from other wineries dealing with similar situations.

Making it easier for wineries to obtain a micro-wholesaler permit would allow them to distribute up to 12,000 gallons per year without an outside wholesaler.

Making it easier for wineries to obtain a micro-wholesaler permit would allow them to distribute up to 12,000 gallons per year without an outside wholesaler.

“It’s a great tool to get our foot in the door, but the restrictions around it are the problem,” Miller said.

The Blackhawk Winery business is in both Miller’s and her husband’s names, which means neither can apply for the micro-wholesaler permit. The couple’s daughter is moving out of state for college, making her ineligible, and their son is only 18 years old.

“We don’t have anybody else to hold it,” Miller said.

Butler said another problem is that the winery needs a micro-wholesale permit to participate in some community events, including the Taste of Bloomington food festival. For that event, Butler said, his winery isn’t actually selling the wine; the organization running the event is. That means Butler has to sell wine to the Taste of Bloomington, but to do that, he needs a distributor.

“There’s certain venues you can’t get into without going through a wholesaler,” he said. “Even if it’s just down the street.”

Opposition to the bill

Two of the big wine distributors—Republic National and Southern Glazer’s—are opposed to the legislation allowing common ownership of a winery and a micro-wholesalers permit.

“It seems a little self-defeating to argue that the only impediment to them getting to market is who owns it,” Purucker said. “They couldn’t get an employee to own it?”

Purucker said his clients are more concerned about how the change could harm the three-tier system and how larger companies could take advantage of the new rule. Plus, he said, they don’t believe the cap would stay at 12,000 gallons.

“We can’t just say it’s only 12,000 gallons,” Purucker said. “That limit will just continue to rise all the time.”

But Miller said she’s not even close to hitting that amount. In 2017, she said, Blackhawk distributed 240 gallons. And if it ever reached 12,000 gallons, she’d want to work with a wholesaler, anyway.

“These permits are really just meant to be a bridge for us,” Miller said. “We don’t want to be in the distribution business.”

Clere said some of the concerns about his bill are misplaced.

“I just want everybody to have more wine,” he said. “It’s frustrating because small producers are finding it increasingly difficult to get their products into retailers and restaurants.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.