Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowMichael McRobbie has weathered the Great Recession, a higher education affordability crisis, and a nationwide reckoning about the very purpose of college—all since 2007, when he became Indiana University president.

But the Australian-born computer-scientist-turned-college-leader hasn’t let that tumult stop him from embarking on a quiet transformation of the giant Indiana public institution that serves more than 91,000 students across seven campuses and has a $3.7 billion budget.

Marsh

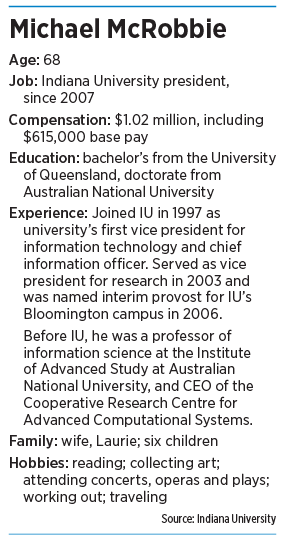

MarshMcRobbie, 68, has both invested in brick-and-mortar and rearranged the academic guts of the university system, all while the school experienced several years of cuts in state funding. State appropriations in 2018 were just 5 percent more than when he started in 2007.

“I really think the sheer amount of change that has happened at IU the last 10 years completely negates the claim that universities are slow to change or impervious to change or that academics hate change,” McRobbie told IBJ. “The amount of change has been huge.”

Across IU, some changes are obvious to the naked eye—and reflect McRobbie’s priorities. He has embarked on $2.5 billion in renovation and new construction of 100 projects on the Bloomington, IUPUI and regional campuses.

There’s the glimmering new, $53 million Global and International Studies Building that echoes McRobbie’s unabashed focus on forging connections overseas, and a $15 million renovation of the IU Cinema, a project that reflects the president’s passion for film and the arts.

Lubbers

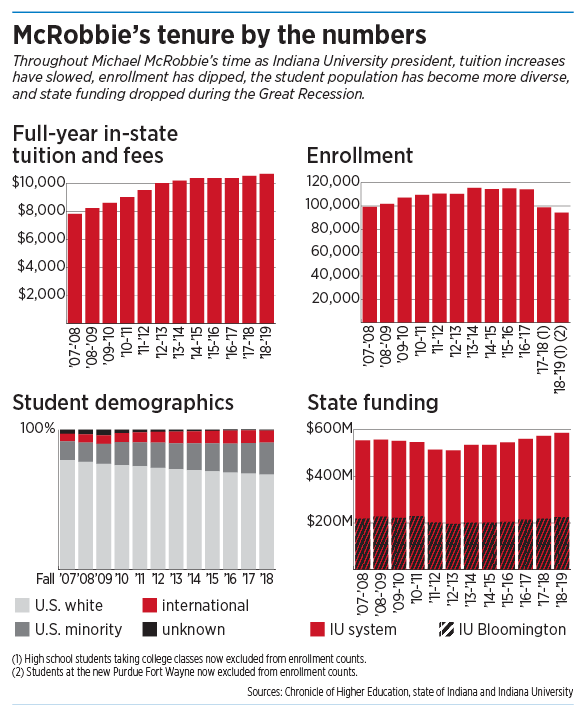

LubbersAnd across all of IU’s campuses, the number of minority students has nearly doubled, to 23 percent.

But other changes are less obvious. McRobbie has completely restructured IU’s academic programs, an unglamorous exercise in changing how a massive educational bureaucracy is organized in a quest to keep up with IU’s peers, improve student recruitment and spur philanthropy.

McRobbie said the academic restructuring was driven by his perception, coming into the job, “that there’s been very little change at IU for a long time” and that it was holding the university back.

“I effectively asked the question, ‘If you were given a budget of $3 billion and asked to design a university system in Indiana, would it look like what it looks like today?’” McRobbie said. “Everybody said no. The second question was, ‘What would it look like?’ There was no agreement on that.”

The university also has made a dent in the student-loan crisis by focusing on financial literacy, a push that included creating a simple, clear letter for students that outlines their future debt responsibilities.

Kravchuk

KravchukThe approach hasn’t grabbed headlines the way Purdue University President Mitch Daniels has for his affordability efforts. Daniels’ initiatives included freezing tuition for seven consecutive years and launching an arrangement under which students can sign over a share of future income in return for help paying for college.

But national higher education experts said they are impressed by McRobbie’s work in the area, which helped reduce undergraduate student borrowing 19 percent, or $126 million, from 2011 to 2017.

Brad Kelsheimer, chief financial officer for the Indianapolis-based Lumina Foundation, which focuses on expanding educational opportunities beyond high school, said universities often outsource their financial literacy programs, and they’re often superficial.

“I’ve not seen one adopted as aggressively as IU,” Kelsheimer said. “It’s certainly a positive outlier based on what we’ve seen.”

Reaching a crossroads?

Now, McRobbie is preparing to lead IU into another major milestone, its year-long bicentennial celebration, which starts in July.

Mirro

MirroBy that time, he’s pushing to have raised $3 billion in IU’s largest-ever all-campus fundraising campaign. And he’s hoping to have a deferred-maintenance backlog that once was more than $1 billion down to zero.

But as McRobbie prepares for more work, others at the university are wondering if they’ll soon get a new leader. News articles recently mentioned him as a possible candidate for the presidency of Georgia Tech University, something he dismissed to IBJ.

McRobbie’s term is set to conclude in June 2021, when a one-year extension he signed in 2015 expires. But according to McRobbie’s spokesman, he and IU’s trustees have agreed to meet in the spring of 2020 to discuss the possibility of extending it beyond that day.

“I’m perfectly happy in Indiana,” McRobbie told IBJ. “I’ll stay in the job as long as the trustees want me to.”

The surprising part of McRobbie’s enduring presidency—nearly 12 years in, he’s far surpassed the average university president tenure of 6-1/2 years—is that he’s done it without ruffling many feathers.

Forbes

ForbesThe way to change a university, he said, is “[being] able to know how to move not too fast, but not too slowly, either.”

“People want to be assured that the change is going to be positive for them, or at least it won’t be negative for them,” he said. “You can’t impose in a university. I think our job has been to help guide this process.”

On the whole, he’s been able to achieve buy-in, even among constituencies sometimes loath to pay homage to university administration.

“There are always things you could complain about with any president or administrator, but over the years he’s figured it out,” said Moira Marsh, an IU librarian and co-chair of the University Faculty Council.

“I think he’s a model president. He’s the best president IU has had since Herman B Wells,” who served as president from 1938 to 1962 and chancellor from 1962 to 2000. “No question. It’s not even a contest.”

Marcus

MarcusTeresa Lubbers, the state’s higher education commissioner, said McRobbie’s tenure has been successful in large part because he “had a clear vision about what higher education needs to do to prepare for the future.”

“The state has been the beneficiary of that kind of vision,” she said. “I think it would be safe to say that, by every measure, IU is a stronger institution now than it was.”

‘Hard to pull this off’

One could argue that McRobbie, who came to IU in 1997 to serve as its first chief information officer, landed the top job at the worst possible time, just as the Great Recession was beginning to wreak havoc on state budgets and students’ wallets.

“It was not how one hoped to start a presidency, I can tell you that,” McRobbie said.

Two years in, then-Gov. Mitch Daniels called for cuts of $150 million to the state’s public higher education institutions, including $60 million from IU.

IU cut back in a range of areas—imposing a salary freeze on most faculty and staff, reducing travel funds, and restricting non-academic hiring, for example—to shift more money to priorities like improving facilities and hiring faculty.

Overall, McRobbie said, the university was still “in very good shape financially” during that period.

“We were still in a position to both hire and build,” he said. “A lot of the elite privates and quite a few of the elite publics had stopped hiring and weren’t giving salary increases, so this was a perfect time to be recruiting. At a time when there was very little commercial building, it was the perfect time to build. There could not have been a better time to be investing.”

McRobbie said he knew coming into the job that IU’s aging Bloomington campus needed a massive overhaul. And nearly $1 billion in maintenance across the entire IU system had been deferred.

“It was clear we were lagging behind,” he said of the campus. But while private donations and low interest rates allowed the university to pay for some of the capital projects itself, it also needed state dollars.

“You can’t raise private money to name steam lines,” he said.

So he embarked on a strategy he discussed with then-Senate Appropriations Chairman Luke Kenley “where we would only ask the state for money for renovation.”

“The taxpayers had put money into these buildings, and you want to continue to ensure they’re used at the highest level of efficiency you [can] reasonably expect,” he said.

McRobbie also tapped a new funding source—revenue from the Big Ten Network, which launched in 2006 and broadcasts sporting events—to invest in such projects as the new Global and International Studies building, and a new academic health sciences building that’s part of the $389 million Indiana University Health Regional Academic Center, a hospital and academic complex under construction in Bloomington.

Big Ten schools have received windfalls in recent years because of distributions from the Big Ten Network and lucrative broadcast-rights deals inked with Fox and ESPN/ABC. IU's share of revenue from the Big Ten Conference jumped from $13.9 million in 2007 to $40.9 million in 2017.

Robert Kravchuk, a professor at IU’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs focusing on public administration, said “he’s really managed to embark on this building program that has not threatened or in any way weakened the finances of the institution.”

IU has maintained the top credit rating from both S&P and Moody’s Investor Service, one of just seven public universities to have the highest ratings from both agencies.

“It’s hard to pull this off,” he said. “Other presidents have looked at their budgets and said, ‘We’re going to spend what we get.’ President McRobbie looks at the budget and says, ‘We’re going to get what we spend.’ He understands the notion of making a strategic investment.”

The affordability crisis

The cost of attending Indiana University has risen during McRobbie’s tenure, but not as fast as at many other colleges.

Average annual published in-state tuition rates rose 29 percent at IU’s Bloomington campus from 2008 to 2018. That compares with an average of 36 percent for universities nationwide.

From 2007 to 2012, IU Bloomington’s in-state tuition rate increased about 5 percent annually, according to data published by the Chronicle for Higher Education. Since 2013, IU has raised tuition an average of about 1 percent annually.

But IU also has cut book and supply fees and other ancillary costs, bringing the total expenses for an in-state student down slightly over the past several years.

But IU also has cut book and supply fees and other ancillary costs, bringing the total expenses for an in-state student down slightly over the past several years.

“President McRobbie has done a great job making sure we’re holding the line on any change in tuition, yet providing the infrastructure and the support the students need to get a quality education,” said Dr. Michael Mirro, president of IU’s board of trustees. “That’s a tough balancing act that, in a time of increasing belt-tightening in higher education, he’s been able to navigate.”

McRobbie said college affordability will continue to be a challenge.

“There’s no one magic bullet,” he said. “You have to be looking at every part of what’s involved in the cost of a university education and be working on all of them simultaneously.”

Experts say financial pressures across higher education are only going to intensify.

One reason is that U.S. universities are struggling to attract international students, who typically pay the full sticker price and thus help hold down costs for other students. New international enrollment in American universities dropped more than 6 percent from fall 2016 to fall 2017, according to the Institute of International Education. In a survey of 500 universities about the decline, more than 80 percent cited the visa-application process and 60 percent cited the “social and political environment in the U.S.”

“I am very concerned about it,” McRobbie said. “I think there’s a perception of the environment being less welcoming than it used to be just a few years ago, plus the added difficulty of getting the right kinds of visas you need to study.”

And then there’s the fact that the Great Recession dragged down birthrates, shrinking the pool of 18- to 22-year-olds who will head off to college in the next decade.

From 2025 to 2029, the population of college students could drop 15 percent and continue to decline in the years after, according to Minnesota economist Nathan Grawe.

“There are some storm clouds on the horizon,” McRobbie said.

‘Put us on the map’

Perhaps the most politically tricky—and unsexy—challenge McRobbie has undertaken was restructuring the university’s academics, toppling old administrative hierarchies and creating new ones.

And he’s done this at a time higher education is suffering something of an identity crisis. Is college about the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, or about training workers for jobs immediately after graduation?

While other leaders have championed a more vocational approach, McRobbie has doubled down on the importance of a classic liberal arts education.

“To me, it is the bedrock strength of the American system,” he said. “That means you value the arts and humanities as much as you value the sciences. You see a well-rounded individual being someone who has had an education across all of them, though they might specialize in mathematics or cello.”

That philosophy—and a desire to better showcase some of IU’s academic strengths—has led IU to create 10 new schools under McRobbie’s tenure.

Those include two schools of public health; a school of informatics; two schools of education; the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy; the School of Global and International Studies; the Media School; and the School of Art, Architecture and Design, which is based in the architectural hotbed of Columbus, 50 miles east of Bloomington.

Those include two schools of public health; a school of informatics; two schools of education; the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy; the School of Global and International Studies; the Media School; and the School of Art, Architecture and Design, which is based in the architectural hotbed of Columbus, 50 miles east of Bloomington.

He also closed the School of Continuing Studies and replaced it with IU Online, which has expanded rapidly, to the point that one-third of all IU students enroll in at least one online course.

“We’ve had this enormous academic strength at IU but most people didn’t know that,” McRobbie said of the decision to pull disparate programs together to form the School of Global and International Studies. “That’s really put us on the map.”

J T. Forbes, CEO of the Indiana University Alumni Association, said the restructuring is an example of McRobbie’s “systems mindset,” and that he knows “how to organize things for greater impact.”

“He’s been a very bold and tenacious administrator in thinking how things should be aligned in order for them to make better sense,” Forbes said. “We haven’t seen that kind of change since the turn of the 19th century.”

Ann Marcus, director of The Steinhardt Institute of Higher Education Policy at New York University, said academic overhauls are “really hard work.”

“It’s very unglamorous, time-consuming work,” Marcus said. “He took on some real challenges and tried to, in a period of resource scarcity, create some things that were new and very interesting.”

McRobbie saw pushback to some changes. For example, some School of Journalism alumni objected to the elimination of journalism as its own school and the folding of that program into the Media School when it launched in 2014.

McRobbie acknowledged some faculty and staff didn’t like changes, but he called them “on the whole very strongly supported.”

‘He’s not burning out’

McRobbie’s presidency has been largely notable for its lack of controversy following the unpopular tenure of his predecessor, Adam Herbert, who was widely criticized as having too low a profile and taking too long to make decisions.

Herbert lost a 2006 no-confidence straw poll of IU faculty, which IU professor of geological sciences and University Faculty Council member Simon Brassell said stemmed largely from “concerns he was dropping too many balls.”

“No one would say that of President McRobbie,” Brassell said. “He’s very much on top of the important things.”

Philip DiSalvio, dean at the College of Advancing and Professional Studies at the University of Massachusetts-Boston and higher education leadership expert, said, “You see presidents crash and burn very often.”

He pointed to last month’s resignation of Carol Folt as chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill over a controversy surrounding a Confederate monument on campus and last year’s ouster of Michigan State University President Lou Anna Simon over the Larry Nassar sexual-assault scandal and cover-up.

“I’d think a person of his stature would have to constantly handle complicated issues, and he’s had to have handled them deftly because he’s stayed under the radar,” DiSalvio said. “It takes great political skill, great interpersonal skill, to be able to maneuver around those issues.”

That doesn’t mean his relationship with faculty is perfect.

“If the faculty were to fault him for anything, it’s that he hasn’t spent more time with the faculty, explaining his vision,” Kravchuk said. “It’s been something we’ve more had to perceive over time. Bringing the faculty along was not always essential, but I think it would have all made them feel a bit better about his leadership.”

Marsh, the IU librarian, said McRobbie’s formality has also been hard for some faculty and students to get used to, as he is “more formal, perhaps, than some Americans are used to.”

“He’s not a warm and fuzzy type,” Marsh said. “But I appreciate that. I wouldn’t say he’s lovable, but he is highly respected.”

Mirro, who has served as a trustee for five years, said he “can’t say enough positive stuff” about McRobbie’s tenure so far, especially considering the higher education world has faced “several significant headwinds nationally over the past decade.”

Next, Mirro said, it’s time to think about the future, specifically that “what higher education looks like in 20 years is going to be significantly different” from the past 20.

Once the university gets past the bicentennial, Mirro said, it will be time to start succession-planning and thinking about who the best leader would be to keep the university moving forward.

The trustees are open to discussing extending McRobbie’s contract, but Mirro also said “we have some extremely talented people within IU that could step forward.”

“I think everything is on the table,” he said.

Mirro noted that on June 30, 2021—when McRobbie’s contract is up—he will have served for 14 years. Few IU presidents have served longer.

“That’s a long time for any college president,” Mirro said. “They kind of burn out.”

But, he said of McRobbie, “he’s not burning out. If anything, he’s accelerating.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.