Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now“If these walls could talk.”

We often say that about old buildings and the significant stories they bore witness to, but I couldn’t help but think about that phrase last month as I toured the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., on opening weekend.

In this case, though, there was no “if”—those walls were talking to me.

Through inscribed quotes, I heard the rarely told stories of enslaved Africans who “willfully drowned themselves” during the transatlantic slave trade, and of the captains who couldn’t take the weeping of those who remained.

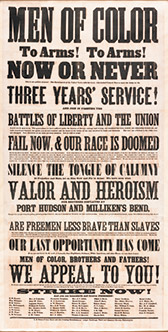

I felt the dashed hopes of blacks promised freedom by both sides of the Revolutionary War, and I got a sense of the deep hatred and terrorism they faced over the following 200 years. But the museum also told stories of fortitude, community, innovation and artistic brilliance—from the black church to the Tuskegee Airmen to the creation of hip-hop.

The museum spoke to me on a visceral level, partly because I’m a black reporter at a news organization that never employed one before me. I’m sure it spoke to many blacks in a similar fashion. But I must say, my visit on Sept. 25 (the day after it opened) proved to me that this museum can speak to all races—as long as they’re willing to listen.

Until now, our stories and our heritage have not had a national place to call home, even as new stories emerge and our culture evolves rapidly. Now they do—in a distinctive, multistory, copper-filigreed building that sits next to the Washington Monument.

Until now, our stories and our heritage have not had a national place to call home, even as new stories emerge and our culture evolves rapidly. Now they do—in a distinctive, multistory, copper-filigreed building that sits next to the Washington Monument.

The 400,000-square-foot building focuses on history on its lower levels—from slavery to the Civil Rights movement and beyond—and culture on its upper floors—including exhibits on sports figures, musicians, artists, inventors and more.

Guitarist Chuck Berry’s shiny red Cadillac is hard to miss, and there are even exhibits on black gestures, black dance and black hair.

The story of the museum dates back to the 1910s, when black Civil War veterans lobbied for its creation. In 2003, Congress charged the Smithsonian Institution with adding it to its roster of museums, and the federal government covered half of the $540 million bill. The rest came from private donations, including $20 million from Indianapolis-based Lilly Endowment Inc.

Designed by black architects, the museum has black curators and is led by a black executive director—Lonnie Bunch III. Several of its 37,000 artifacts came from the descendants of black people and black communities.

“For me, it represents the opportunity for us to be the writers of our own unedited stories, because often our stories are edited by other people in history,” said Kim Herrell, 52, a visitor from Sacramento, California.

She later added, “This to me is a beautiful reflection of where we’ve been and where we can go.”

Sights and sounds

My wife, Kathryn, and I had been eyeing the opening of the free museum since April. Demand forecasts were so high that the museum had to distribute timed tickets to avoid everyone showing up all at once.

I guess it helped, but it was hard to tell. The lines we encountered outside would put Thanksgiving airport security lines to shame. A museum spokeswoman told me 31,025 people visited Sept. 24-25.

I found the museum’s layout efficient and self-explanatory. Once inside, you ride an escalator from the expansive atrium down to Concourse 0, which hosts a theater named after benefactor Oprah Winfrey and a 400-seat eatery that could’ve been named anything and still would have won me over. (For the record, it was called Sweet Home Cafe and I did eat there later.)

From there, you descend 70 feet in a glass elevator to the lowest level and work your way back up through concourses 1-3 via ramps. The concourses, filled with exhibits and multimedia, take visitors on a ride through history, starting with the indescribable horrors of a slave trade that sent millions of Africans to the Western Hemisphere beginning in the 1400s.

I did not plan to be in writer mode that weekend, but I pulled out my recorder and notepad when I noticed a white woman lifting her glasses to wipe tears while watching a looping video about children being sold into slavery.

Her name was Kimberly Stanley, 48, of LaGrange, Georgia, and she was there with her black husband, Anthony Stanley. She stressed the relevance of the museum in light of racial tensions in America today.

“With everything that’s going on in our nation now,” she said, “how can I as a white person understand what someone else feels unless there’s a place like this for me to learn?”

I saw far more Caucasian, Asian and Hispanic people during my visit than I expected. I overheard one white man explaining the concept of slavery to a boy who appeared to be his son, about 7 years old. I saw one white woman who, several times, covered her face and turned her head watching a video about lynchings.

Regardless of your race, some exhibits—like the casket and photo of brutally killed teen Emmett Till—were just tough to witness.

“There’s a lot of stuff you don’t want to remember,” said Joseph Davis, 72, of Temple Hills, Maryland.

Indiana connections

Indianapolis is well represented at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture for entrepreneurship, above, and sports, right. (IBJ photos/Jared Council)

Indianapolis is well represented at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture for entrepreneurship, above, and sports, right. (IBJ photos/Jared Council)As you might have expected, 20th century Indianapolis entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker—born Sarah Breedlove—made appearances in exhibits on black business, black hair and several others.

But there were some lesser-known Hoosier ties as well, including a prominent exhibit featuring Lyles Station, a southwestern Indiana settlement founded by freed slaves in the 1840s. Artifacts included farming tools, school items and a jar of soil. Fourth-generation farmers still cultivate crops on fields in Lyles Station.

I was most fond of the Negro League Baseball exhibit, which featured two items from Indianapolis. One was a burnt orange stadium seat from the former Perry Stadium (which was renamed Victory Field in 1942 and Bush Stadium in 1967). The second was a 1940s-era advertisement for a game between the Kansas City Monarchs and the Harlem Stars at that stadium.

Another Indiana connection worth noting is Lilly Endowment’s $20 million donation. The not-for-profit is one of only three benefactors to donate that much. Half came in 2010 to help kick off the museum’s private-sector fundraising campaign; the other $10 million came in 2015 to establish the Center for the Study of African American Religion.

“The new National Museum of African American History and Culture is a magnificent addition to the cultural resources in our nation’s capital,” said Endowment President, CEO and Chairman Clay Robbins.

“Its design and exhibits vividly portray the compelling narrative of the unimaginable adversity and indomitable spirit of African Americans in this country.”

Breaking for lunch at Sweet Home Cafe doesn’t end the cultural experience. The menu featured dishes categorized by region: The Agricultural South, The Creole Coast, The North States and the Western Range. The closer I got to the front of the extensive line, the more I salivated.

Tempted by the “Gospel Bird” platter—buttermilk fried chicken brined and floured over three days, mac-and-cheese, greens, yams and biscuits—I chose instead to be adventurous. So I opted for Son of a Gun Stew, a classic cowboy dish of the American West.

The stew featured medium-rare short ribs, hearty potato slices and corn in a red-wine reduction. It also carried flavorful sundried tomatoes, which extended the dish’s sweet notes. I was able to pull aside Executive Chef Jerome Grant, who told me the stew pays homage to freed slaves who migrated west and took jobs on chuck wagons preparing food for railroad builders.

“Every three months, we’ll have a new seasonal menu,” Grant said. “And we focus on the ingredients and the stories of those areas.”

Promise and paradox

I spent about 10 hours in the museum, and one thing that stood out to me is the number of paradoxes in the African-American story.

The new Smithsonian is filled with historical documents and artifacts. And even the cafe has a cultural focus. (Courtesy of National Museum of African American History and Culture)

The new Smithsonian is filled with historical documents and artifacts. And even the cafe has a cultural focus. (Courtesy of National Museum of African American History and Culture)We fought in wars to achieve and maintain freedom, but were hardly able to participate in that freedom. We put our money in banks that wouldn’t give us loans. We got jobs at predominantly white newspapers, but our stories—deemed potentially offensive—were censored.

“I wrote a story every morning,” one museum exhibit quoted journalist Robert Churchwell as saying, “but it never got in the paper.” Churchwell, who became the Nashville Banner’s first black reporter in 1950, was referring to stories he wrote about the explosion of student-led protests and sit-ins in the 1960s.

One of the biggest paradoxes relates to Martin Luther King Jr.’s ideal of being judged by character, not color. We are becoming blind to race, arguably a good thing. But with that we’re becoming blind to systems of racial injustice that are probably going to take decades to dismantle, just as they took decades to build.

The museum displayed a quote from Princeton professor Naomi Murakawa that sums it up well.

“If the problem of the twentieth century was, W.E.B. Du Bois’ famous words, ‘the problem of the color line,’ then the problem of the twenty-first century is the problem of colorblindness, the refusal to acknowledge the causes and consequences of enduring racial stratification.”

One visitor told me the museum was a “living, breathing, dynamic monument of healing.” I believe its power comes from the stories it tells through its walls, its exhibits.

My wife and I can’t stop talking about those largely untold stories, and she started tearing up the other day doing so.

“We needed that museum, man. And not even just ‘we’ as in black people. America needed that museum,” she said. “We now have a full American story.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.