Subscriber Benefit

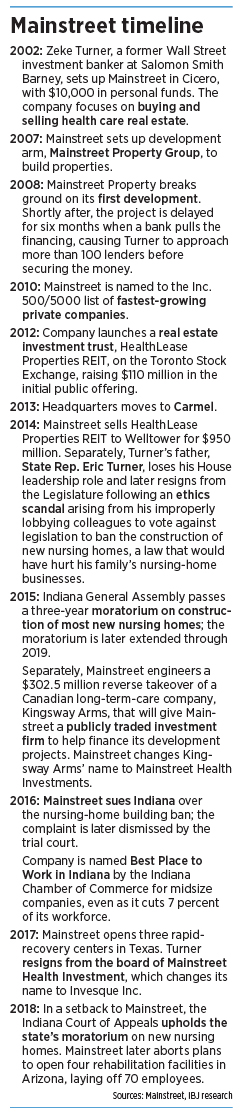

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowFor more than a decade, Zeke Turner built a reputation as a whirling dervish in the nursing-home business, building scores of senior-care facilities and vowing to shake up an industry he said had become tired and complacent.

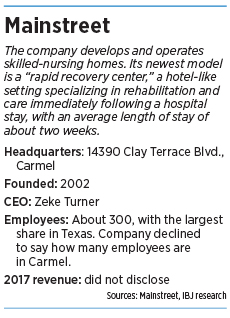

His company, Mainstreet, which he founded in Cicero in 2002 and moved to Carmel in 2013, raised tens of millions of dollars from investors and lenders. Over the years, Turner went on a hiring spree, recruiting more than 100 employees, many of them highly paid specialists in construction, marketing, fundraising and business development.

But in the past year, Mainstreet has been reeling from an unexpected slowdown in sales of its properties—a reflection, at least in part, on rising vacancies in nursing facilities and a trend toward home-based care. Meanwhile, a moratorium on building nursing homes in Indiana, imposed in 2015, has dried up construction business in Mainstreet’s home state.

In response, Turner has been quietly cutting dozens of jobs in Indiana and moving most of his company’s operations to Texas, where he is investing heavily in a new business model: high-end, short-term recovery centers for patients who have undergone hospital medical procedures and need around-the-clock skilled-nursing attention for a few weeks before they’re ready to go home.

In response, Turner has been quietly cutting dozens of jobs in Indiana and moving most of his company’s operations to Texas, where he is investing heavily in a new business model: high-end, short-term recovery centers for patients who have undergone hospital medical procedures and need around-the-clock skilled-nursing attention for a few weeks before they’re ready to go home.

The company has spent more than $50 million developing the concept, building the centers, and staffing and opening the first two in Texas. Two others are set to open soon, with an additional four planned by the end of the year.

But as it makes the transition, Mainstreet has watched revenue fall and employees depart.

The setback is a blow for Turner, 40, who built one of the fastest-growing companies in Indiana and is now trying to rescue it.

“No question, 2017 was a tough year for us,” he said.

The downturn is humbling for a company accustomed to turbo-charged growth. From 2011 to 2013, Mainstreet’s revenue grew 480 percent, to $66.3 million, making it the fastest-growing private company in central Indiana.

In 2014, revenue hit $118.9 million, for a two-year growth spurt of 89 percent. Turner declined to give last year’s revenue figure, saying numbers were not finalized.

By 2015, Mainstreet’s headquarters was packed with workers. The company pulled down top honors in 2016 from the Indiana Chamber of Commerce as the best place to work in the state among midsize companies. The company has been named to Inc. 500/5000, a ranking of fast-growing private companies, seven times since 2010. Turner won Entrepreneur of the Year in 2015 from Ernst & Young LLP for the Ohio Valley region.

The picture is much different now. Several former employees say head count at the Carmel headquarters is below 30, but Turner declined to provide a number.

“I don’t think it’s relevant,” he said.

In recent weeks, the company handed out its latest round of pink slips, many of them in Carmel. Turner declined to say who was let go but put the number of terminations at “about five or six.” But that was at least the third round of cuts in the past 18 months.

Righting the ship

The downturn raises questions about whether Turner can turn things around during a tough time in the industry—and how much of the company will remain in Indiana.

Nationally, occupancy in skilled-nursing facilities reached a new low in the third quarter of 2017, at 81.6 percent, according to the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care.

An analysis released last month by Avalere Health found Medicare beneficiaries spent 15 percent fewer days in skilled-nursing facilities in 2016 than in 2009. Much of that is due to hospitals’ sending patients home, cared for part time by visiting nurses and other home health care professionals, rather than to short-term, skilled-nursing facilities.

David Gordon, an Atlanta lawyer who specializes in business bankruptcies and insolvencies in health care, said there’s “a lot of pain” in the industry now, as providers watch their bed counts drop and some go out of business.

“There’s all sorts of pressure to innovate and do something new,” Gordon said. “Maybe these guys [at Mainstreet] have found an answer. If so, kudos to them.”

To meet the changing landscape, Turner is overhauling the company’s central mission. For years, the company’s business model was to build nursing homes and lease them to outside management companies, then act as landlord and collect the rent. Mainstreet would sell the properties a few years later for sizable profits, plowing the proceeds back into new developments.

It was a model that required a relatively modest workforce and lots of outside partners.

Now, Mainstreet is itself staffing and operating the “rapid recovery centers” it has started building, instead of leasing out those functions. That move is a big bet because each facility is manned by dozens of nurses, therapists, coaches and support staff, requiring a large payroll.

As a result, company employment has actually doubled in the past year, Turner said, from about 130 last April to “just shy of 300.”

To help finance the growth, the company raised $15 million last year from investors. And it is back in the market right now, trying to raise additional money, he said.

The moratorium

So while Mainstreet’s head count is shrinking in Indiana, it is swelling in Texas. And for the time being, Turner doesn’t see Indiana as a large part of the company’s future.

He puts much of the blame on the Legislature’s moratorium on new licenses for nursing homes and transitional-care facilities. The nursing home industry said Indiana had thousands of unused nursing home beds and didn’t need more.

Mainstreet and its affiliated entities had nine nursing home projects across the state in various planning stages when the moratorium took effect. Mainstreet had executed land-purchase agreements for sites in Zionsville, Jeffersonville, Fort Wayne and New Haven, but had not yet closed on the properties.

Along the way, the Legislature’s actions caught Turner’s father in an ethics scandal. Eric Turner, then one of the top Republicans in the Indiana House of Representatives, was quietly lobbying his colleagues to kill an early version of the moratorium bill. But he was embarrassed when an Associated Press investigation found he had millions of dollars on the line as a large investor in his son’s company.

After the disclosure, Turner was removed from his House leadership position in August 2014 and resigned from the Legislature three months later.

After the moratorium bill passed, Mainstreet sued the state in 2016, trying to get the law declared unconstitutional. A trial court dismissed Mainstreet’s complaint, and last month, an Indiana Court of Appeals upheld the moratorium, which runs through 2019.

Now, Turner said he is looking elsewhere to grow his company and is winding down much of its presence here.

“There’s not a compelling reason for us to have a full staff in Carmel,” he said. “If my wife and I didn’t live here and have family here, I might not have any staff here at all.”

Turner doesn’t even refer to Carmel as company headquarters anymore. Instead, he calls it a “resource center”— home to a tiny staff made up of his office, the company’s financial administration and some human resources functions.

Meanwhile, to help administer the expanding Texas operations, the company has shifted its business development and property operations to Cedar Park, a suburb of Austin, accounting for about 50 white-collar jobs.

“The core of our company is shifting,” Turner said.

‘It was a good model’

When Turner founded Mainstreet 16 years ago, he saw it mainly as a buyer of health care real estate. Then, in 2007, he set up the building division, which has built about 50 projects.

To help provide a source of funding, Turner in 2012 launched HealthLease Properties REIT, a public real estate investment trust that traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The Turner business model thrived by selling nursing homes his company built to the REIT at sizable profits, often up to 25 percent. Then Mainstreet would use the proceeds to develop more properties.

“It was a good model,” Turner said.

In August 2014, Turner sold HealthLease for $950 million to Ohio-based Health Care REIT Inc. That company, which is now named Welltower, also agreed to acquire 17 projects Mainstreet had under construction that were valued at $369 million and to fund development of 45 more senior-care campuses valued at $1.4 billion.

A year later, Turner engineered a similar REIT deal, buying a Canadian long-term-care company, Kingsway Arms, which traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The move was intended to replace Mainstreet’s main capital source and property purchaser.

A year later, Turner engineered a similar REIT deal, buying a Canadian long-term-care company, Kingsway Arms, which traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The move was intended to replace Mainstreet’s main capital source and property purchaser.

Turner set up the REIT in the same building as Mainstreet, 14390 Clay Terrace Blvd., and installed several Mainstreet executives to run it. He changed Kingsway’s name to Mainstreet Health Investments. Turner had a 5 percent stake in the REIT and installed himself as board chairman.

But before long, the new REIT began to go its own way. It announced in September 2016 that it had “internalized” its management team, rather than having Mainstreet executives run the operation.

“The entire senior management team will become employees of the company,” the REIT announced. It also said it planned to buy seven senior-care and health properties worth $152 million, including four from Mainstreet in Texas and Kansas. But three were from outside developers, a trend that would grow.

The parting

Over the next 18 months, the REIT’s newly independent management showed relatively little interest in Mainstreet properties. To date, it has bought fewer than 10, representing a small fraction of its portfolio of 103 properties.

In September 2017, Turner announced he was resigning from the REIT’s board, and he liquidated his ownership interest.

Two months later, the REIT changed its name to Invesque Inc. It plans to next month move out of the building it shares with Mainstreet and into offices three miles away on West Main Street in Carmel.

“Today, we have zero relationship with Mainstreet,” said Scott White, Invesque’s CEO, who is a former chief operating officer for Mainstreet. “We are a 100 percent independent, public company with no overlapping employees or anything.”

White

WhiteThe parting seems to suggest a falling-out between the companies, but Turner said he stepped away from the REIT to focus his time and effort on Mainstreet.

“I do not have insight to Invesque’s decision-making or strategy, but we have enjoyed a good working relationship,” he said. “In the last year, we transacted on nine properties and may do more business together in the future.”

Even so, the split threw cold water on Turner’s plans.

“In early 2017, our model broke down,” he admitted. “Invesque didn’t want to do as much buying from us as HealthLease did.”

That forced Mainstreet to start from scratch in selling its properties, rather than having a steady buyer down the hall. Selling the properties one or two at a time was no easy task, with each carrying a price tag of $20 million to $25 million.

“Those don’t sell overnight,” Turner said.

Of the more than 50 properties Mainstreet has built since its founding, it has found buyers for 42. The company has nine properties up for sale.

New direction

Turner said his team began working on its new focus—rapid-recovery centers—in 2014. The concept fills the bridge between hospital and home, he said, with a hotel-like setting that provides full-time skilled-nursing care without the high price of an inpatient room, and with less 0risk of a relapse.

The need for such a bridge comes from insurers’ pressure on hospitals to release patients sooner than in the past, he said.

The Mainstreet centers feature large patient rooms with contemporary decor, an on-site chef, a coffee-shop-style cafe, social gathering spaces and entertainment. The average length of stay would be 10 to 14 days.

“Many patients no longer feel like they’re stuck in a hospital, anxious to be discharged, because at RRC they’re able to enjoy many of the same experiences they would have during a hotel stay,” Mainstreet said in a promotional flier.

It took Mainstreet three years to develop the concept, raise money and break ground. The first opened last year in Waco, Texas.

Average cost ranges from $420 to $450 a day, Turner said, a fraction of the daily hospital inpatient recovery rate.

It remains unclear whether the concept will catch on. A few years ago, as Turner was rolling out his concept, some industry experts took a decidedly skeptical view.

“I don’t know what they’re smoking, but maybe they know something I don’t know,” Vincent Mor, a professor of health care services, policy and practice at Brown University, told IBJ in 2014. “Right now, the occupancy rate in most skilled-nursing facilities is relatively low precisely because there are fewer people hospitalized.”

Now, four years later, Mor is still not convinced the idea can work. He said rapid-recovery centers are today’s version of what the industry tried a decade or two ago without success, under a different name.

“These were ‘continuing care centers’ where patients could co-habit with the spouses while waiting for or recovering from surgery,” Mor said. “Many of these places on the campus of hospital systems were converted into ambulatory care offices or ambulatory surgery, which was far more profitable as same-day surgery expanded. To my knowledge, no one is doing this for post-acute-care rehab and recovery since payment models are quite limited.”

Fierce competition

Victoria Perez, an expert on health care finance, said she was unable to see how patients or insurers would save money, when a popular, low-cost alternative is to recover at home, sometimes with visiting nurses or other home health care. She said that route has proven to help patients heal and avoid expensive hospital readmissions.

Perez

Perez“It sounds like Mainstreet is marketing themselves like a boutique hotel setting,” said Perez, an assistant professor at Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs in Bloomington. “That might be OK, if people have private insurance and that’s where they want to spend their recovery. … But I’m not quite clear on where the cost savings would come from.”

Some observers say the rapid-recovery centers might catch on if Mainstreet can get insurers to see that the centers could save money, compared with high-cost hospital stays.

Medicare has been paying for post-acute rehabilitation care for decades. But the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has been pushing to lower costs with shorter recovery times and lower readmissions rates, while improving outcomes.

Nursing homes and skilled-nursing facilities are competing fiercely for those patients.

“Succeeding in the changing Medicare environment is something that all providers are working on, as utilization is not growing as some expected,” said Zachary Cattell, president of the Indiana Health Care Association, a nursing home trade group.

Cattell

CattellBut even as it rushes into this area, Mainstreet already has stumbled. Last fall, the company announced it would open four rapid-recovery centers in Arizona, a state with a large population of elderly people, many of whom need somewhere to recover after hospitalization.

Mainstreet hired scores of workers in Arizona, began construction, and geared up for grand openings.

But last month, Turner stunned employees with the news that the company was aborting the Arizona rollout. Instead, it laid off more than 70 workers there and put the properties up for sale. Only one had actually opened and was treating only a few patients on a trial basis.

Turner blamed higher-than-expected startup costs and a “challenging reimbursement environment.” He said he regretted the pain to workers, but in the end, didn’t have enough money to develop and staff Texas and Arizona at the same time.

“I think we’re trying to be very cautious about where we’re spending dollars and making sure we have the money in the right place,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.