Subscriber Benefit

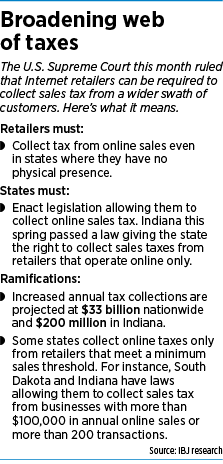

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThis month’s U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said states can require retailers to collect sales taxes from their online customers could mean millions of dollars of revenue for states, including Indiana.

Cockrum

CockrumBut a number of Hoosier companies say the ruling creates more questions than answers—and could lay a burden on some small businesses that's too heavy to bear.

Jim Cockrum, CEO of Greenwood-based Cockrum Computer Services Inc. and host of a podcast aimed at internet-based business owners, said the June 21 decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair Inc. “has opened a whole can of worms.”

“This is overwhelmingly confusing to every expert on the topic,” said Cockrum, whose firm offers consulting and training conferences related to selling in online marketplaces. “I’m telling my clients not to panic, keep serving your customers and growing, and keep good records because this could be a nightmare.”

Casey Gauss, CEO of Indianapolis-based Viral Launch, called the ruling “a huge headache” for online retailers. Viral Launch sells software subscriptions and services that help mostly private-label sellers boost online sales, many through Amazon.

Gauss

Gauss“A lot of these companies are just now focusing on growth,” Gauss said. “This could pull resources from that effort.”

One thing is certain. Indiana state officials are ready to use the ruling to ignite legislation passed in 2017 by the General Assembly that calls for companies—no matter where they are located—to collect and remit Indiana’s 7 percent sales taxes on goods purchased by Hoosiers online.

A Marion County judge put that law on hold, pending the outcome of the South Dakota case. Now, the Indiana Department of Revenue will ask the local court to allow it to begin enforcing the law.

“The Department of Revenue is ready to roll,” said the agency’s commissioner, Adam Krupp. “Our system is capable and ready.”

Implementing the law could be fruitful.

A 2017 study published by the University of Tennessee concluded that Indiana lost $195 million in 2012 in uncollected sales taxes. That figure is likely much higher now, experts agree.

The state has been able to collect some online sales taxes through agreements with nearly 2,000 companies, including Amazon. But most companies have refused to charge their customers taxes for online purchases, including some independent companies that sell their wares through Amazon.

By law, consumers are supposed to pay that tax themselves when they file their income tax returns. However, according to a fiscal analysis from the Legislative Services Agency, the state collected only $2 million in 2016 in use tax from tax returns.

Mumford

Mumford“This ruling means the state is going to bring in 100 times more than that,” said Kevin Mumford, a Purdue University associate professor of economics. “It’s a nice windfall for the state, and it could have a very big impact in even more rural states with few corporate headquarters, warehousing operations or physical retail outlets.”

The latest Supreme Court decision overturns a 1992 ruling that states could not require the collection of sales taxes by companies that did not have a physical presence, like a store or warehouse, in that state.

That decision—in Quill Corp. v. North Dakota—helped pave the way for the growth of online retail by letting companies sell nationwide without navigating the complex patchwork of state and local tax codes. It also gave online companies a pricing advantage over their brick-and-mortar competitors.

Two camps

Opinions on this month’s ruling fall into two distinct camps.

One view—including that of Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb and many state lawmakers—heralds the decision. They say it creates a level playing field between brick-and-mortar and online retailers, and provides an avenue for states, cities and other local governments to regain revenue they’ve lost as buyers moved to online purchases.

The other camp includes online buyers who like sidestepping the tax as well as the small and midsize online retailers who worry some buyers will reduce their online purchases if the costs go up.

Many of those firms also say the ruling will create an undue burden in the form of thousands—possibly tens of thousands—of dollars each year in compliance costs to administer the collection and remittance of the tax to states and other taxing entities.

Cockrum sighed when asked about leveling the playing field. “Why is the solution to leveling the playing field a new tax?” he said. “Couldn’t it be lowered on the other side [through a lower sales-tax rate]? So now, consumers pay the price to have a level playing field.”

Some online sellers also worry that states might attempt to collect online sales taxes retroactively.

The Supreme Court ruling highlights South Dakota’s plan not to require companies to remit sales taxes for past purchases. But laws in some states—including Indiana—allow for at least limited retroactivity, a provision likely to be litigated if the state tries to collect.

Owens

Owens“This is a pretty significant burden for small businesses that sell online,” said Josh Owens, CEO of Indianapolis-based SupplyKick, an online retailer for wholesalers, handling product storage, marketing and shipments. “It’s certainly not the best thing that could be happening for online retailers.”

Owens, whose company mostly sells through Amazon, doesn’t think the regulation will hamper his business much.

“We’ve been doing sales taxes so long, this is something we’ve planned around,” he said.

SupplyKick, which was founded in 2013, has inventory in more than 30 states and currently remits sales taxes in more than 20 of them, Owens said.

That can be complicated. Companies that have sales in just half of U.S. states could have to deal with more than 5,000 taxing entities.

“It’s not just 50 different state tax laws that online companies have to be concerned about,” Purdue’s Mumford said. “There are many, many smaller taxing entities in each individual state, county and city. And a closer look shows there’s even more complexity than that.”

Owens pointed out that different states and municipalities have different collection cycles. “They collect quarterly, monthly, and different states require different receipts as documentation,” he said.

Companies that sell the largest variety of items online and in the largest number of states will suffer the most, Owens said.

SaaS concerns

Locally, concern might be greatest among companies that sell software as a service—software that is delivered digitally on a subscription basis, rather than through disks purchased at a store.

That arena is already complicated, as states try to sort out whether sales tax applies to those purchases at all.

“As an Indiana company that provides web-based services to out-of-state customers, I now have to worry about whether my services are subject to sales tax in other states, counties, cities, towns, etc.,” said Ray Ontko, president of Doxpop LLC, a Richmond-based firm that helps customers gain access to public records and other legal information. “This has the potential to become a huge burden for Indiana companies doing web-based sales.”

Indiana lawmakers this year exempted SaaS from sales taxes. But that law applies only to sales made to companies and people inside the state. SaaS sales outside the state—even from Hoosier companies—could be subject to taxation, depending on the laws of the states where the purchaser resides.

“We have an awful lot of SaaS companies in this state,” Cockrum said. “This could have a dramatic impact on those firms, depending on how this shakes out.”

Some critics of the Supreme Court’s decision point out that the case involves Wayfair, a company that sells goods, not services. Therefore, it might not apply to software sold as a service. Cockrum, for one, said “it’s totally unclear” how the ruling affects SaaS companies.

But multiple legal experts interviewed by IBJ agreed that software companies would be required to collect sales taxes in states that mandate it.

Only three states have laws that impose sales taxes on SaaS products. Another 13 impose sales taxes on such software under agency rules. Thirty-five states and the District of Columbia either don’t tax SaaS products or don’t have a sales tax.

Limits on states

Limits on states

Legal experts say the ruling sent a strong message that states have to offer some of the same protections to companies that South Dakota does in its law—or face legal challenges down the road.

“We think this ruling will affect the law in every other state,” said Verenda Smith, deputy director of the Federation of Tax Administrators, a not-for-profit that serves to state tax authorities and administrators.

By pointing out several stipulations in the South Dakota law dealing with online sales taxes, the court “is not saying every state has to do these things, but they’re giving really strong hints,” Smith said.

Some key elements of the South Dakota law that the Supreme Court highlighted:

◗ South Dakota’s law has a minimum threshold (only companies with $100,000 in annual sales and/or 200 transactions will be required to collect sales taxes on online sales).

◗ Businesses have no obligation to remit sales taxes retroactively.

◗ South Dakota is one of more than 20 states that have adopted the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement—a system that standardizes taxes to reduce administrative and compliance costs.

◗ South Dakota provides sellers access to sales tax administration software paid for by the state. Sellers who choose to use such software are immune from audit liability.

Smith said the court is making clear that laws that meet those criteria don’t create an undue burden for companies that have to comply.

“No state has [it] within its interest to destroy small businesses,” she said.

Indiana’s law includes most of these provisions.

The state is part of the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement. The organization that implements the streamlined tax program certifies and subsidizes software for companies to use to comply—and provides immunity to companies that use it.

That’s important, said Purdue’s Mumford, because, without computer software to manage all the rates and rules, compliance would be nearly impossible for most small and many midsize businesses.

‘Nobody knows’

SupplyKick’s Owens said the cost of buying or leasing such software and dealing with the sales tax issue overall could be $10,000 or more annually.

“The point is, nobody knows,” Cockrum said. “I don’t think $25,000 a year to deal with this is an unreasonable estimate. In fact, I think when you consider the professional accounting and legal assistance a company will need to track things like tax rates, threshold rates and information that needs to be tracked on filing deadlines and accompanying documentation on an annual basis, $25,000 [annually] is a very conservative estimate.”

Indiana’s law also includes the $100,000 and/or 200-transaction threshold before a company is required to collect sales taxes.

Owens said it’s not uncommon for startups to rack up online sales in excess of $100,000. “That’s sales, not profit,” he said. “Those are very much considered small businesses.”

Cockrum predicted that many companies will intentionally stop selling in certain states just short of the threshold.

“This will only hurt the states where this is enacted,” he said. “It’s going to deprive the citizens of that state of certain goods and services. And the ruling will send tech companies running the other way from those states.”

Betz

BetzDespite such objections, Indianapolis attorney Kevin Betz is betting Indiana will prevail in its quest to collect the tax.

He said it’s no coincidence that Indiana’s law closely mirrors South Dakota’s.

“The National Conference of State Legislatures was surely involved in jointly drafting of legislation for states that wanted to collect online sales tax,” said Betz, who, as managing partner of Betz & Blevins, has a focus on constitutional and federal law. “They wanted to make sure that, once the Supreme Court ruled, there was no argument or as little argument as possible in other states where state legislation was enacted.

“The Supreme Court appears to be telling other states what would be enforceable. They’re saying South Dakota went about this the right way to make this enforceable. And Indiana looks to be one of the first in line ready to follow.”

Cockrum isn’t convinced.

“This is going to be challenged in court, maybe here, maybe elsewhere,” he said. “It’s going to take months, if not years, to shake this out. Because of the complexity of this, I think [the law] will implode on itself.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.