Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowJust 16 months ago, things were looking bleak for Endocyte Inc.

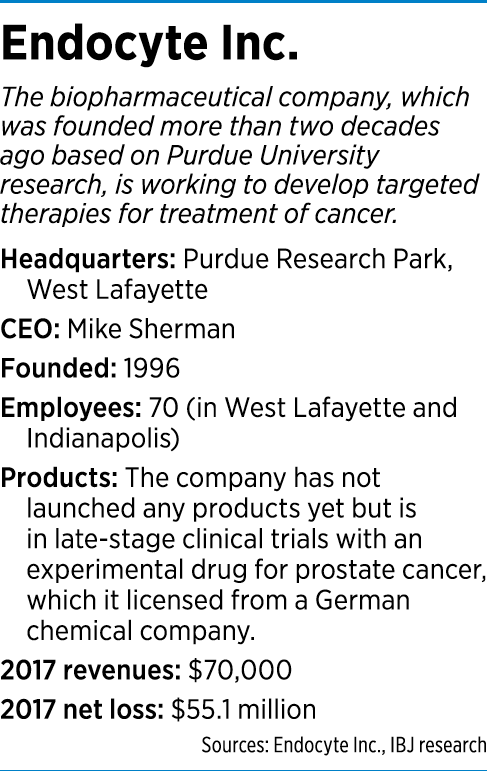

The West Lafayette-based biotech, which had been trying for more than two decades to develop smart cancer drugs, stunned investors and employees when it announced in June 2017 it was halting tests of a leading compound and laying off 40 percent of its staff.

Shares plunged 30 percent on the news. CEO Mike Sherman held a conference call for analysts, but when he threw it open for questions, not a single person asked one. After years of watching the company weather one setback after another, Wall Street apparently had lost interest.

“That was definitely a low point,” Sherman recalled.

But these days, investors are flocking back with a vengeance.

On Thursday morning, Endocyte shares soared 51 percent after the company announced it had agreed to be bought by Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis AG for $2.1 billion, or $24 a share, a premium of 54 percent over Wednesday’s closing price.

On Thursday morning, Endocyte shares soared 51 percent after the company announced it had agreed to be bought by Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis AG for $2.1 billion, or $24 a share, a premium of 54 percent over Wednesday’s closing price.

The rich deal created an enormous payoff for many investors, who had seen the shares sink as low as $1.41 last fall, following multiple setbacks and restructurings.

The Novartis deal also provided validation to Endocyte’s decision last year to put its own pipeline on the back burner and focus on developing a drug for prostate cancer that it had recently acquired from a German chemical company.

That compound called 177-Lu-PSMA-617, is viewed as a widely promising therapy for a serious condition called castration-resistant prostate condition. About 100,000 men a year die of prostate cancer in the U.S., Japan and Europe.

Novartis said it viewed the drug as a potential blockbuster, meaning it could generate sales of more than $1 billion a year. Already, it has shown promising results in mid-stage clinical trials and is now in late-state tests.

Earlier this year, Endocyte announced it had reached an agreement with federal regulators that could speed up development. That got investors’ attention. Even before the Novartis deal was announced, Endocyte’s stock had jumped tenfold in the past 12 months, as Wall Street gradually began to believe the company was turning a corner after burning through more than $100 million since its founding its 1996.

But to get the finish line, Endocyte still has to shepherd the compound successfully through months of late-stage clinical trials and hope for positive results. It’s not a slam dunk: Nine of every 10 drugs that go into clinical testing in the U.S. are scrapped along the way because they don’t show strong enough results. Of 14 major disease areas, new cancer drugs have the lowest rate of success: just 5.1 percent.

Still, Endocyte investors seem buoyed by the possibility of success, despite the company’s multiple setbacks. Some observers say it is a normal state of affairs in the topsy-turvy world of drug development.

“Many biotech companies go through setbacks before they launch, because of the uncertainty in drug discovery and development,” said Jack Pincus, president of BioStrat Consulting, an Indianapolis life sciences consulting firm. “But there is a set of investors who will take these kinds of risks because the payoff can be very, very large.”

Early efforts

If Endocyte—or Novartis—can deliver now, it will be a crowning touch to decades of struggles—a wild ride that has provided a few major jolts along the way.

Endocyte traces its roots to the Purdue laboratory of chemistry professor Philip Low. In the early 1990s, he discovered a method for delivering drugs selectively to cancer cells. Cancer cells replicate uncontrollably and have an enormous appetite for the vitamin folate to fuel their growth, absorbing it through special receptors.

Low found a way to use folate as a carrier to deliver attached drugs—or “warheads”—to the cancer cells. He published his findings, and soon his phone began ringing off the hook from interested venture capitalists.

Low said he had no idea at the time what a venture capitalist was or how to start a company. He eventually called a friend, Jack Clawson, then the CEO of Hillenbrand Industries, a Batesville-based maker of hospital supplies.

“With no intention of getting him involved, I just asked him, ‘Can you tell me about VCs and give me some advice on how to respond to all these inquiries,” Low said.

Clawson asked to see the data, and a few days later, told Low he would invest $1.5 million—from himself and some colleagues—in exchange for two-thirds of the start-up company. Low would get the remaining one-third.

Clawson also recommended that Ron Ellis, a Hillenbrand vice president, run the company as CEO, allowing Low to concentrate on his scientific research. Low agreed, and Endocyte began as a two-person operation.

Most of the initial research was done in Low’s labs, where his team used folate to piggyback an imaging agent called diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid, or DPTA. Low got permission from the Food and Drug Administration to administer DTPA to cancer patients.

“We got back the images, and they showed a beautiful uptake into the cancer tissue,” Low said. “That was right at the beginning, confirmation in real people with cancer that folate could be exploited to deliver attached drugs.”

With that validation, the company began developing a wide array of imaging and therapeutic agents to find cancer cells and kill them.

For years, Endocyte touted its experimental “smart drugs” for finding and fighting cancer cells with technology that could deliver a high dose of therapy to diseased cells, while leaving healthy cells untouched. Such technology could help save tens of thousands of lives, the company said.

From 2001 through 2004, Endocyte received a total of $4 million in grants from the state’s 21st Century Research and Technology Fund. The company began hiring more researchers and business managers to help it develop the products and find markets for them.

Endocyte later raised millions more in venture capital from investors including Indianapolis firms CID Capital, Clarian Health Ventures and the Indiana Future Fund. The latter was launched by the life sciences initiative BioCrossroads in 2003.

Another big investor was the pension fund of the Indianapolis-based Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), which kicked in more than $10.3 million and at one point held a 15 percent stake.

In 2008, Endocyte was named one of Indiana’s “50 Companies to Watch” by the state for its success in raising funds and in creating jobs.

In 2011, the company—then with 54 employees—went public. It had no products on the market—just a pipeline that it said could lead to exciting new drug treatments. The IPO raised $75 million, but only after the company cut the price twice, to $6 a share.

Endocyte stock ups and downs: Click the dots for more information

Pursuing a treatment

At the time of the IPO, Endocyte was in the second of three stages of clinical trials needed for U.S. approval for its most advanced drug, called vintafolide, or EC145, for ovarian and lung tumors.

Endocyte was able to point to strong results from early trials. Women receiving the treatment in a phase 2 trial saw a 105-percent improvement in progression-free survival compared with women receiving the standard therapy.

Based on the strong results, Endocyte raised another $60 million in another stock offering in 2013.

Around this time, Endocyte struck up a partnership with drug giant Merck & Co. Under the deal, Merck would help develop and market vintafolide, and Endocyte could get more than $1 billion if the drug was successfully developed as a treatment for multiple types of cancer.

It was a heady time. By 2014, Endocyte was being mentioned as a possible premium takeover target after it reported that vintafolide slowed the progression of lung cancer and won European backing to treat ovarian cancer.

Then, in a stunning reversal of fortunes, things suddenly fell apart.

In May 2014, Endocyte and Merck pulled the plug on vintafolide in the midst of phase 3 trials after an analysis showed that it didn’t demonstrate effectiveness in treating patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Endocyte said it would continue to study the compound for lung cancer.

But the company’s shares, which had climbed as high as $28.17 per share, plunged 62 percent in one day to under $6.

Endocyte had spent 13 years to get to that point and had little to show for it. At the time, it had 70 employees at Purdue Research Park in West Lafayette and 25 in Indianapolis and had been hiring people in Europe to support the launch.

“Of course, it was a shock,” Ellis told IBJ shortly afterward. “There were literally people that had left jobs and come to work at Endocyte for this launch.”

Two years later, Ellis would leave the company, and the board replaced him with Sherman, Endocyte’s longtime chief financial officer.

A year after that, in June 2017, Sherman had his own low moments, when he decided to scale back the company further, discontinuing trials on a cancer drug called EC1456 and narrowing development of another cancer drug, EC1169, to include only certain types of patients. As part of the move, Endocyte said it would cut about 30 jobs, leaving it with 47 employees.

Finding its footing

By then, investors were running out of patience. Shares fell 30 percent the day of the layoffs, trading below $2. And analysts were done valuing Endocyte as a red-hot start-up with huge earnings potential.

“We value the company at cash,” Wedbush Securities analyst David Nierengarten announced in a sobering note to clients.

Yet in the following months, Sherman pushed on, looking for a new direction. He said he had no regrets about his decision to pause development of his own company’s pipeline.

“When I took the CEO role and assessed the internal pipeline, we agreed as a group we would put a high hurdle on what we needed to see in those drugs,” Sherman said. “And if we didn’t clear the hurdle, then we were going to stop development. It was the right thing for patients and the right thing for investors.”

The hurdle was pretty simple to define, he added. “We were looking for certain rates of tumor reduction. So if you don’t see the tumor shrinking at a certain rate, we need to move on.”

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Endocyte was negotiating with German chemical company ABX GmgH, for the worldwide licensing rights to its late-stage prostate cancer drug.

The drug had largely been developed by a group of German physicians for “compassionate use settings,” or drug of last resort. And the data, Endocyte decided, looked promising, and linked closely to technology that Endocyte was familiar with.

The target of the drug was prostate specific membrane antigen, or PSMA, a protein expressed in virtually all prostate cancers. It’s a type of pharmaceutical called a small-molecule drug conjugate, which Endocyte had been researching and developing for years.

After months of negotiation, Endocyte made another momentous announcement in October of 2017: It would put almost all of its internal pipeline on the back burner and make a multimillion-dollar bet on the German company’s drug.

Endocyte said it had acquired worldwide licensing rights for an upfront payment of $12 million, along with up to 6 million shares of Endocyte stock, which were then trading at $1.41 each.

It was a major moment for Endocyte—an admission that its own pipeline was not the best route for success.

When asked last fall if Endocyte was betting the farm to acquire the experimental prostate drug, Sherman responded to IBJ: “I don’t know if I would use the phrase ‘bet the farm.’ I would say this is absolutely the right bet and the smart bet to make.”

But for Low, the Purdue chemistry professor who developed the technology and served as the company’s chief scientific officer, that decision stung.

He still saw huge potential for vintafolide—the drug that flopped in treating ovarian cancer—to treat non-small-cell lung cancer. Merck’s independent tests, he said, showed that the drug increased overall survival of lung-cancer patients from 6.6 months to 12.5 months.

“It was very frustrating,” Low said. “I personally didn’t believe it should have been dropped. But I’m not a businessman and don’t understand all of the parameters that have to be considered. And for large companies, unless they can see a huge market, they often don’t want to move something forward.”

But Sherman said he was confident that the restructuring and new strategy was the correct course for Endocyte, after burning through millions of dollars without launching a single product.

Last month, Endocyte pleased investors with the news that federal regulators had agreed to a new endpoint on a late-stage clinical trial for the German company’s drug. Rather than having to show benefits in overall survival, it will only have to show something called “radiographic progression-free survival”—meaning the time it takes for a tumor to start growing again as determined by X-rays.

Measuring rPFS is faster than measuring overall survival, so that could cut a year off the development of the drug, wrapping up the analysis by the end of 2019.

Several analysts quickly upgraded their recommendations on Endocyte stock. And four days later, the company said it had raised another $189 million through a public stock offering—its second of the year. In March, it had raised $81 million.

For Sherman, it amounted to a big year: raising more than $200 million and striking a key agreement with the FDA that turned investors’ heads.

The company’s market value has soared to $1.9 billion—the highest ever for a Purdue startup.

Some Indianapolis biotech veterans give Sherman huge credit for the company’s turnaround.

Fritz French worked in the executive suite with Sherman at Guidant Corp., the medical-device spinoff of Eli Lilly and Co., more than a decade ago, before it was sold to Boston Scientific Corp. in 2006. He still remembers him as driven, intelligent and persistent.

“What he’s done for Endocyte to get the company on such a positive trajectory has been very challenging and took a lot of creativity, not a small task,” French said. “It’s been quite an impressive turnaround.”

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.