Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now Martens

MartensA wave of corporations in central Indiana is creating venture capital arms, pushed partly by the desire to join the technological movement.

While corporate venture capital dates back to 1914, when DuPont invested in private startup General Motors, more corporations have jumped into the game in the last decade, for a variety of reasons.

“We’re definitely seeing a big swing up in this direction,” said Rob Martens, president of Indianapolis-based Allegion Ventures, the venture capital arm of Dublin-based Allegion, a security-products company with its North American headquarters in Carmel.

“Everyone has a little different mentality toward corporate venturing. It’s definitely not one-size-fits-all,” Martens said. “But there are big advantages to it, and that’s why I think you’ll continue to see it grow.”

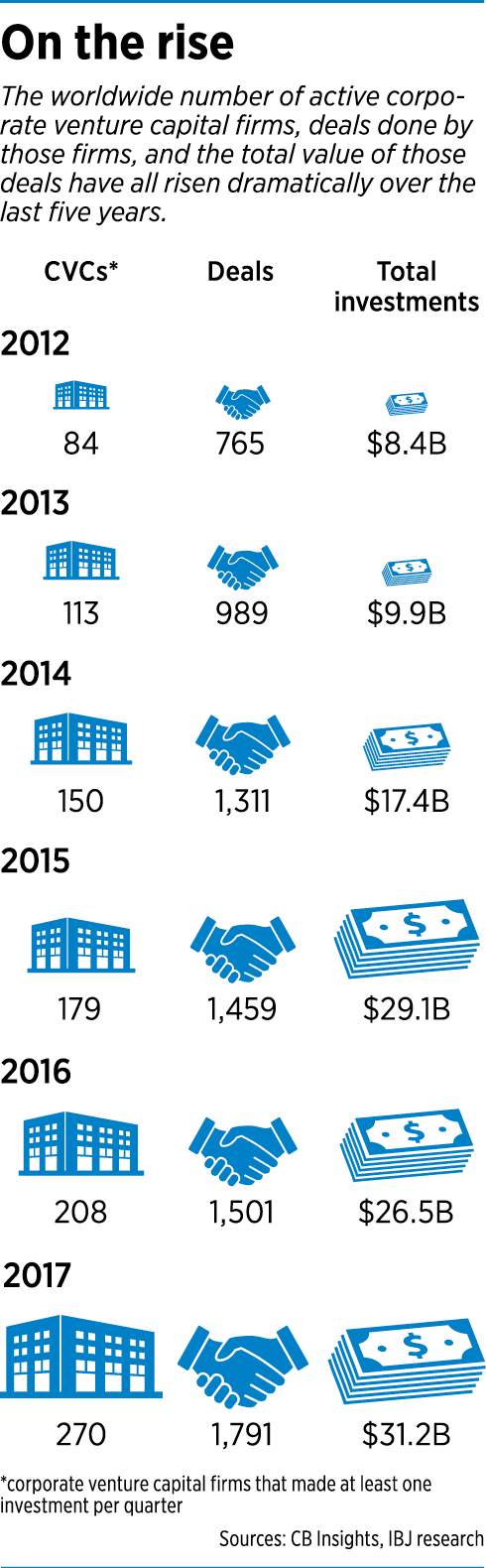

The number of active corporate venture capital operations globally has exploded from fewer than 85 in 2012 to more than 300 this year, according to CB Insights. The firm defines “active” as operations that make at least one investment per quarter.

The number of active corporate venture capital operations globally has exploded from fewer than 85 in 2012 to more than 300 this year, according to CB Insights. The firm defines “active” as operations that make at least one investment per quarter.

When less-active operations are included, the number of CVCs worldwide nears 1,200, experts say. That’s an estimate that has more than tripled in the last decade.

And the number of deals conducted by CVCs has climbed from 765 in 2012 to 1,791 last year, while the total amount of those deals climbed from $8.4 billion to $31.2 billion in the same time frame, according to CB Insights.

“The impact of this movement on the startup ecosystem locally, nationally and globally has just been tremendous,” Martens said. “And the financial resources these organizations bring to the table is just part of the picture. The human resources capital they bring can’t be overlooked.”

Until recently, corporate venture capital was the realm of global heavyweights. Eli Lilly and Co. was one of the first on board locally, when it created Lilly Ventures in 2001 with $175 million.

In 2009, Salesforce—which is based in San Francisco but has a sizable presence in Indianapolis—launched Salesforce Ventures and quickly became one of the most active CVC operations globally.

Simon Property Group Inc. launched Simon Ventures in 2014 “to support the companies that are at the forefront of driving innovative consumer experiences.” Firms it has backed include Indianapolis-based SmarterHQ, which sells software that helps retailers personalize the online shopping experience.

This year, two more local CVCs launched—Allegion Ventures in March and HG Ventures in August. HG is affiliated with The Heritage Group of Indianapolis, which has holdings in environmental services and remediation, specialty chemicals, fuel products and construction.

Many CVCs are tightly connected with the company that launched them. Such is the case for Allegion and HG Ventures. Lilly Ventures reorganized in 2009 as an autonomous subsidiary of the drug giant.

Alternate priorities

There are two fundamental differences—besides the ownership structure—between a corporate venture capital operation and a traditional venture firm.

Unlike traditional venture capitalists, corporate venture capital firms typically don’t raise outside money, instead pulling the money from the parent firm’s balance sheet.

Frey

FreyAnd while CVCs certainly want a return on their investments, they’re usually not driven solely by financial gains, as a traditional venture capital firm is.

“I wouldn’t say that a financial return on investment isn’t an important measure of success,” said Kip Frey, The Heritage Group’s executive vice president of new ventures and head of the company’s venture arm. “But success is measured in a number of different ways. We’re in a position to look at it from a broader lens.”

For Salesforce Ventures—the only CVC focused entirely on enterprise-software firms—the monetary return is secondary, said Matthew Garratt, managing partner. The first priority is to “build an ecosystem of partners” and get access to numerous innovations, he said.

“We really came at it from: How do we solve our customers’ problems?” Garratt said. “Salesforce Ventures is focused 100 percent on creating the world’s largest ecosystem of enterprise cloud companies and extending that technology to our customers.”

Garratt

GarrattNot that Salesforce Venture hasn’t had a number of successful exits. In the nine years since Salesforce Ventures formed, 14 of the companies in which it has invested have gone public and more than 50 more have been acquired. Many—including Dropbox, Survey Monkey, Evernote and DocuSign—have had significant success.

“We’ve been fortunate to have a really strong portfolio,” Garratt said.

Neither is it Salesforce Ventures’ primary goal to buy the companies it has invested in, having acquired only a handful.

But CVCs do want to make money. Part of the reason Lilly Ventures became an autonomous subsidiary was so it could pay its managers more when their investment decisions generate spectacular returns. Before that reorganization, its employees couldn’t take a cut of profit because of restrictions in Eli Lilly’s compensation policies.

Acceleration

The first wave of tech companies joined the VC fray in the early 1980s and a second, larger wave joined in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The likes of Google Ventures, Intel Capital and Microsoft Ventures, along with Salesforce Ventures, are now among the most active CVCs.

Hanak

Hanak“Much of the recent activity is technology-driven,” said John Hanak, managing director of Purdue Ventures. “With technology developing as rapidly as it is, there’s a real desire to stay on top of that—and investing in and partnering with emerging companies is seen as one way to do that.”

But firms launching venture-capital operations aren’t necessarily technology giants, Allegion and The Heritage Group being prime local examples.

Still, Hanak said, “these firms certainly employ a fair amount of technology and are interested in innovation,” and having a venture arm “is a good way to stay close to those things.”

Some see the CVC trend as a way for corporations to augment their research and development.

“These venture arms allow companies to keep abreast of new developments without incurring new costs and undo risks involved with research and development,” Hanak said.

Others said the venture divisions are actually a replacement for company-funded R&D.

“If you go back 10 to 20 years, many of these companies would have full-on research and development departments,” Frey said. “That model has become too capital-intensive for a lot of companies. This is a more efficient alternative.”

Sometimes, the strategy provides other benefits. For instance, Salesforce Ventures—which in 2017 was the world’s third-most-active CVC behind Google Ventures and Intel Capital—has been known to invest in companies that serve not only Salesforce but also Salesforce’s numerous clients.

Dale

Dale“A variety of [corporate venture capitalists] have deployed this strategy—Sprint, UPS, Gordon Food Services and Northwest Mutual Life. Having a [venture arm] is an opportunity for them to have someone full-time looking for companies that will positively affect the parent company in a big way,” said Frank Dale, who has worked for several startups and early-phase companies and is now co-founder and CEO of local tech firm Costello.

The two biggest advantages for corporations with venture capital arms are “access to talent that isn’t necessarily in the market you are in and exposure to new processes,” Allegion’s Martens said.

CVCs are a good opportunity for companies to “double dip,” Dale said. Not only do they get the equity benefit of investing in companies that could provide a big payout, but they also get a company that boosts the parent’s bottom line. And if things work out really well, he said, the company operating the venture arm could have an inside track in acquiring the early-phase company.

Pros and cons

Because most corporations are less motivated by direct financial returns, CVC initiatives are often lauded for applying less pressure on startups. Venture experts said the typical CVC looks to recoup three times its investment within 10 years, while a traditional venture capitalist aims for two to three times that return in the same period.

Because most corporations are less motivated by direct financial returns, CVC initiatives are often lauded for applying less pressure on startups. Venture experts said the typical CVC looks to recoup three times its investment within 10 years, while a traditional venture capitalist aims for two to three times that return in the same period.

Officials for Allegion Ventures and HG Ventures said they don’t have a targeted return on investment at all.

“There are different ways you can look at value,” said HG Venture’s Frey.

The tempered expectations can be especially beneficial for startups in industries that face significant government regulations, such as life sciences or clean tech, which refers to firms that focus on clean energy or sustainable products and services.

CVCs are also hailed for bringing more expertise and in-kind resources to the table than traditional venture capitalists.

“We don’t make investments unless we think we can bring something else to the enterprise,” Martens said. “Corporate venture capitalists bring a deep knowledge that can help a startup.”

This level of expertise, Martens said, is why traditional venture capitalists often bring corporate venture firms in on deals.

“Corporate venture capitalists are often intimately familiar with the market, and that gives comfort to financial venture capitalists,” he said.

Purdue Ventures’ Hanak added: “For a startup, access to talent and expertise is every bit as important as access to capital.”

But some corporate venture capital operations have also been derided for acting slowly. They can be burdened by management layers within the larger corporation, the kind of bureaucracy tangle startups and innovators disdain.

“In some cases, large corporations have to change their mindset,” Martens said. “It’s all about not wasting a startup’s time, because they’re burning cash every day they’re in business. You have to have the mindset of doing things at the speed of a startup, not an established, large, multi-national company.”

HG Ventures appears to be moving relatively quickly. Only three months after its official launch, it has examined 31 deals and engaged in 15 of those, Frey said, with an aim to invest $50 million annually.

Speed is no problem for Salesforce Ventures, Garratt said, noting the operation’s more than 275 investments in the last nine years.

“We’re an innovative, fast-moving company,” he added. “That’s just our culture. Because a lot of these [startup] companies are working on thin budgets—the founders may not be taking a salary and they’re often on an accelerated schedule—they appreciate that.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.