Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowDevi Davis and April Angermeier are challenging the cash bail system that keeps poor people awaiting trial locked up in Marion County jails, often putting their jobs and homes at risk.

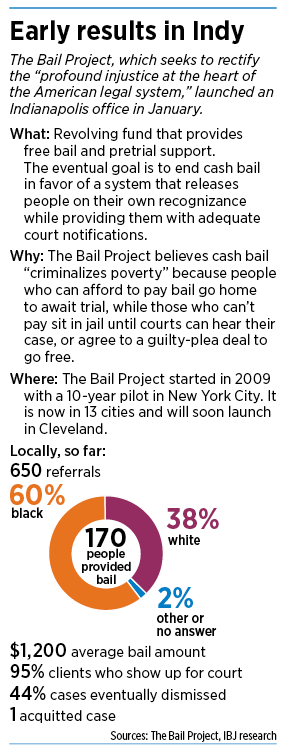

Since mid-January, the pair has bailed out 170 men and women from Marion County jails through a new not-for-profit called The Bail Project, which recently expanded to Indianapolis and about a dozen other U.S. cities after starting a decade ago in New York City.

The primary work of The Bail Project is to use charitable donations to post bail for people stuck in jail only because of their inability to pay. In all the cases The Bail Project works on, a judge has said the accused are allowed to return home to await trial as long as they pay the bail, which essentially is a refundable deposit to make sure someone returns to court. That bail, which runs from hundreds of dollars into the thousands, is returned to the group’s revolving fund once the case is over.

Criminal justice reform advocates say the current bail system creates a two-tiered justice system: one for the affluent and another for the poor. People with disposable income often can quickly pay bail, go home, keep their jobs, and resume their normal lives while they await their day in court.

But people without the ability to bail themselves out face tough decisions: They end up sitting in jail for days, weeks or months, putting their jobs and homes at risk. Or they plead guilty to lesser crimes so they can go home—and end up with a criminal record they might have avoided.

Hackett

Hackett“What we provide is the opportunity for them to fight their case from a position of freedom,” said Davis, who has more than 20 years of experience working inside Indiana’s court system, including in setting bail in Marion County jails. “The only reason they’re sitting there is money.

“I don’t think people understand the impact even a few days in jail has on a human life and their entire family. They can lose everything: their home, their children, their job. It’s so difficult to get back on the right track.”

Indianapolis resident Mike Maloy, 25, said The Bail Project bailed him out when he was charged with domestic battery early this year. The case eventually was dismissed, but he said he spent at least five weeks in jail. Getting out allowed him to more easily work on the case with his lawyer.

“It was almost like a miracle,” Maloy said. “It was hard while I was incarcerated. If I would have stayed incarcerated, it probably would have been prolonged or a plea might have been involved. It was my only hope of survival for winning this case.”

“They can’t save the world, but I think what they’re doing is saving a lot of people’s lives,” he said.

Big aspirations

The ultimate goal of The Bail Project, which is based in California, is to reduce mass incarceration by reducing the number of people in jail awaiting trial. A 2019 report by the Prison Policy Initiative found that, of the roughly 621,000 people held in jails for local authorities, about three-quarters, or 462,000, have not been convicted of a crime.

About 2,500 people are held in Marion County’s three jails on any given day, with 85% awaiting trial, according to Lena Hackett of the Marion County Re-Entry Coalition.

Melton

Melton“Bail seems like a small part of the system, but it’s actually integral to the entire system,” said Camilo Ramirez, The Bail Project’s director of communications.

Ramirez said the group wants to prove there’s a fairer method than cash bail to make sure people charged with crimes come back to court: Release people on their own recognizance and provide adequate court notifications and support services.

Besides providing bail money, Davis and Angermeier, and their fellow “bail disrupters” in other cities, provide their clients Uber rides and cell phones (plus text them court-date reminders), and help arrange for child care and obtain bus passes.

“The whole bail system rests on the assumption that, without [a money deposit], people are not going to come back to court,” Ramirez said. “The Bail Project’s intervention proves that’s wrong. When people miss a court appearance, it’s usually because of involuntary circumstances. Ultimately, people come back to court because, if you don’t, there’s going to be a warrant.”

The early results of the project in Indianapolis are promising: So far in this city, 95% of Bail Project clients have returned to court. In addition, 44% of the cases The Bail Project has taken on have ended with the charges dismissed. In one case, the defendant was acquitted.

“An arrest is not a conviction,” said John Cocco, director of re-entry services for Step Up, an Indianapolis HIV service provider.

“If they’re held on bail, they might lose the job we helped them find, or lose the housing we just got for them. Out of jail, they can continue to plead their innocence. That’s to the benefit of the person and to society generally.”

How it works

The Bail Project works on referrals from places like the Marion County Public Defender Agency, other lawyers, social service agencies and the public.

Since January, the Indianapolis team has received 650 referrals, mostly from the public defender agency. A handful have come from the Fathers and Families Center, a Marion County social-service provider.

“It has been a Godsend,” said James Melton, family services manager for the Fathers and Families Center. “It can take so long for most of the individuals we serve to come up with money.”

Davis and Angermeier review all referrals to see if the arrested people meet the group’s eligibility requirements: They have to have been arrested in Marion County, and they can’t be held on a surety bond, which essentially requires a private loan transaction through a bail bondsman. The group also factors in a person’s likelihood to return to court.

One thing the pair doesn’t care about? The charge. They take the judge’s word that the defendants are able to be out in society awaiting trial as long as they pay bail.

“We’re not in the business of making those judgments,” Angermeier said. “If a judge has established a cash bail, that means the judge is comfortable with that person being in the community.”

The Bail Project’s Indianapolis team has paid as little as $250 to bail out a client who sat in jail for over a year on the lowest-level felony charge. The average bail amount is $1,200.

“We’ve paid $250 bonds because that is too much for someone to pay,” said Angermeier, who previously was a public affairs consultant and heard about the position through her work with the Marion County Re-Entry Coalition. “For some people, that seems like nothing. For others, that is everything and makes all the difference.”

After bailing people out of jail, Davis and Angermeier offer—but don’t require clients to accept—support services, such as help finding housing, getting a job or accessing health care.

After bailing people out of jail, Davis and Angermeier offer—but don’t require clients to accept—support services, such as help finding housing, getting a job or accessing health care.

“They don’t owe us anything in return,” Davis said. “We just want them to overcome any barriers they face in getting to and from court.”

The Bail Project said about half of their clients take advantage of those services.

“The big thing we’re trying to do is meet clients where they’re at and let them be in the driver’s seat for once,” Angermeier said, “rather than us deciding what’s going to help them. We’re finding people stay in touch with us when that’s our approach.”

Elizabeth Wallin—founder of Project Lia, a transitional employment program for women coming out of jail or prison that repurposes discarded materials into accessories and home furnishings—has had a few workers referred to her from The Bail Project.

“What I see as so important about The Bail Project is, there’s somebody there saying, ‘You’re important, and I’m here to help you and work on this with you.’”

The team also has expanded into helping people with outstanding warrants surrender and resolve their cases, which criminal justice experts say is a significant problem in Marion County.

Davis said it’s to the community’s benefit to help people get right with the law.

“Serving warrants is very dangerous, even for police officers,” Davis said. “It’s a way for individuals to feel safe and feel comfortable and take care of something that has totally controlled their life.”

‘Pleasantly surprised’

The group has been a welcomed new resource in Marion County, said Ann Sutton, chief counsel for the Marion County Public Defender Agency.

“It’s been really good for our clients,” Sutton said. “We were pleasantly surprised about their follow-up with clients once they’ve posted bond.

“They’ve been really hands-on and positive with the clients, helping them figure out life stuff, like jobs and where to live. A lot of people say they’re going to do that, but to put the words into action has been phenomenal.”

However, Sutton admitted some in the local criminal justice system were skeptical of the project at first.

“Any time you’re talking about bond and bail, it evokes certain emotions in people,” Sutton said, “and being afraid of letting the wrong person out. The biggest concern is just the unknown.”

Though The Bail Project nationwide has helped thousands go free without a hitch, there have been a couple of tragedies.

Most notably, a St. Louis man in April was accused of committing first-degree murder the same day The Bail Project posted his bail.

The group said at the time that it was “deeply saddened,” but that “it’s important to remember that, had he been wealthy enough to afford his bail, or bonded out by a commercial bail bond agency, he would have been free pretrial as well.”

Hackett of the Marion County Re-Entry Coalition said “all of the actuary tables and risk assessments are not always going to work.”

“They’ve bailed thousands of people out,” she said. “We don’t want to raise so much anxiety that everybody is kept in jail because we’re terrified of people we don’t need to be terrified of.”

The Bail Project is expected to operate for two years in Marion County. It expects to bail out about 50 people per month, Angermeier said.

“We want to work ourselves out of a job,” Davis said, by providing enough successful data through their efforts to show that cash bail is unnecessary.

Hackett said the Marion County Re-Entry Coalition wants the county to end the cash bail system in favor of one that decides whether to hold people in jail based solely on their risk to re-offend. That approach would be in line with a 2016 Indiana Supreme Court ruling encouraging courts to release low-risk offenders without setting bail. Since the ruling, several counties have been participating in a pilot program, with favorable results.

In lieu of bail, Hackett said, modern tools like text messages and robocalls are more cost-effective ways to make sure people return to court.

Reducing the local jail population would be fairer and more efficient, she said.

The cost to jail someone in Marion County ranges from $54 to $78 a day, Hackett said. “The ultimate goal is to get away from money bail. This is one step toward that.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.

More drivel from the left.

“The only reason they’re sitting there is money” How about the real reason…. they are accused of committing a crime !!!!!!!!!

Interestingly, the only way The Bail Project is able to operate in Marion County, is because the judges agreed to not deduct fines and costs from their cash bail deposits. Hard-working Hoosiers who deposit their own a cash bail with court are not afforded the same benefit, they pay.

In Marion County it is not about Justice, it is all about Just U$$.

Also, the “risk assessment” being used across Indiana to determine the likelihood someone will appear for court, has been determined to be biased against minorities. Just this year, Colorado, Iowa, Idaho, Florida, Kansas and Texas legislatures rejected the risk assessment scheme. Hopefully, Indiana will figure this out soon and discontinue tue use of risk assessment tools for pretrial release.