Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowJust a few minutes northeast of vibrant Monument Circle lurks the most notorious graveyard of Indianapolis’ industrial heyday.

Step to 22nd Street and the Monon Trail, look half a mile in all directions, and you’ll survey at least 70 of the city’s 500 abandoned commercial and industrial sites. It’s the greatest concentration of brownfields in the city.

The area doesn’t have a name, per se, in that it spills across several neighborhoods, such as King Park and Martindale-Brightwood.

A site where Colonial Bakery maintained vehicles is just one of a number of brownfields in an area where a Monon Railroad roundhouse once anchored a thriving industrial center. The location is now owned by King Park Area Redevelopment Corp. and awaits a new use. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)

A site where Colonial Bakery maintained vehicles is just one of a number of brownfields in an area where a Monon Railroad roundhouse once anchored a thriving industrial center. The location is now owned by King Park Area Redevelopment Corp. and awaits a new use. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)For every occupied house in the worst part of the zone, another is boarded up. Or there’s not a house at all—just an empty lot sprouting weeds and trash. It might as well be a rotting neighborhood of Detroit; there’s even an automobile factory that closed 86 years ago.

Progress is often measured first by annihilation. This spring, an excavator scraped from the face of the Earth the former Titan Industries plating plant, 2422 Yandes St., whose treasures included rusty chemical drums.

Progress is often measured first by annihilation. This spring, an excavator scraped from the face of the Earth the former Titan Industries plating plant, 2422 Yandes St., whose treasures included rusty chemical drums.

“I know the neighbors are happy,” said Chris Harrell, the city’s brownfields redevelopment coordinator, “because the rat problem has decreased.”

Yet for all its blight, the area could be among the most significant urban revitalizations in decades anywhere in the state. It’s close to downtown just as urban

living is becoming cool again. Running straight down its middle, alongside the Monon, is the former Nickel Plate rail bed proposed as a commuter rail line linking downtown and Noblesville. It could give those who live in the brownfields area access to jobs downtown and in the suburbs.

“The rail line would be the biggest economic development stimulus to this neighborhood in decades,” said Will Pritchard, a principal of Development Concepts Inc., an Indianapolis firm with several projects planned for the brownfields area.

Visionaries are salivating over the idea of creating a community where people live and work and even grow their own food in urban gardens atop once-contaminated sites.

“We have significant, significant amounts of contamination,” said Brad Beaubien, director of the Indianapolis office of Ball State University’s College of Architecture and Planning. Yet, “It doesn’t make sense to dump money in it [for remediation] and let it remain fallow. … It’s definitely a grand vision, but it does have a lot of potential.”

Early industrial site

Transforming a legacy of heavy industry and the environmental and social problems that come with it will take lots of time, money and tolerance for risk.

The area, which includes the western edge of Martindale-Brightwood, was a railroad center in the 1870s. Visible to this day in aerial photos is the circular outline of a former locomotive roundhouse the Monon Railroad operated just south of 28th Street and the Monon Trail, when the trail was a busy rail line.

Up and down the tracks were machine shops supporting the railroads, fuel depots and manufacturers that enjoyed easy access to the rails. Among them was National Motor Vehicle Co., at 1145 E. 22nd St.

National Motor Vehicle is said to have made the second car to win the Indy 500 and to have built America’s first six-cylinder stock car, with a neck-snapping (back then) 75 horsepower. An advertisement for National’s “Sextet” model said it could accelerate “from two to forty miles an hour in a city block.”

National had only a 24-year run, ceasing operations in 1924. By then, much of the railroad activity had moved from the area to rail yards that sprang up in Beech Grove.

Part of the former National Motor Vehicle Co. plant has been renovated for The Project School charter school, and a developer plans to revitalize the rest to house small businesses. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)

Part of the former National Motor Vehicle Co. plant has been renovated for The Project School charter school, and a developer plans to revitalize the rest to house small businesses. (IBJ Photo/ Perry Reichanadter)The National site later was used by numerous manufacturers and eventually as a warehouse, with its glass panes covered over with corrugated steel siding. Its iron lattice-truss water tower still stands, incredibly. On the south end of the plant, along the abandoned “Bee Line” tracks that once served the facility, was an illegal dump that included buried gasoline tanks. The city and CSX railroad booted the dumper in recent years.

But on the north end of the sprawling plant is a gleaming school city planners hope is a harbinger of more revitalization.

Situated in National’s former design studio is The Project School, a K-8 charter school approved by Mayor Greg Ballard in 2008. Development Concepts spent more than $2 million to convert the offices into the school.

Development Concepts plans to redevelop the rest of the factory, about 200,000 square feet, into the National Design Factory. The company has been targeting creative businesses—such as those focused on art, architecture and engineering—as potential tenants. There’s space for perhaps 40 firms.

“We’ve talked to a lot of companies,” said Pritchard, who is whittling down a list of good fits.

The auto factory complex would be stripped of its corrugated metal siding to reveal its former glory of expansive windows and brick façade.

Other parts of the complex are also eyed for reuse. The city and the Indianapolis office of Local Initiatives Support Group, a New York-based organization that helps communities with revitalization, have put up $30,000 toward studying soil at the site to see if it is safe for students to use for urban gardening.

In fact, Harrell is working with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as well as state and local officials to develop a protocol for determining soil safety, in what could be a national model.

“Hopefully, by next spring, we’ll have some areas that are safe to grow,” Harrell said.

Nearby, in a 12-acre strip south of East 23rd Street and east of Ralston Avenue, work is under way to reuse a former Mobil Oil fuel depot. Exxon Mobil has already removed lead from the site, and plans to install groundwater monitoring wells at this former site of the Douglas Little League ball fields. They were closed in the 1980s after heavy amounts of lead were found.

Plans for atop the brownfield include a massive sports complex with two baseball diamonds and soccer, rugby and football fields. Shepherd Community Center, a ministry that operates its Jireh Sports facility on the north end of the site, already has detailed plans for the complex and is trying to raise money to build it.

Douglas Little League team is believed to be the second-oldest continually playing African-American team in the nation, said Tim Streett, assistant director of Shepherd Community. The team has been playing at other fields since lead was found.

“We want to return Douglas Little League to the neighborhood,” Streett said.

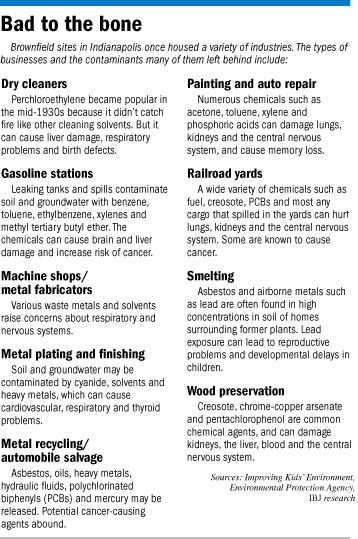

Nasty variety

Success has already come in a big way for one of the nastiest neighbors—the former Ertel Manufacturing site, 2045 Dr. Andrew J. Brown Ave.

The city used more than $6 million in state and federal grants to clean up the Superfund site, contaminated with material from asbestos to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). More than that, the site has been reused as part of a $19 million expansion by Major Tool & Machine that added more than 50 jobs and retained 270 existing ones.

The city used more than $6 million in state and federal grants to clean up the Superfund site, contaminated with material from asbestos to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). More than that, the site has been reused as part of a $19 million expansion by Major Tool & Machine that added more than 50 jobs and retained 270 existing ones.

But big sites are the exception; most of the progress comes in smaller bites. Slowly maneuvering his staff car over one-time Bee Line tracks near 21st and Sheldon streets, whose crossing lights haven’t flashed red in years, Harrell is surprised to find that the former, three-story Linder Machinery building is now a pile of bricks and twisted steel. Nearby, what’s left of Linder’s big steel beams are cut into sections and loaded atop a truck, to be hauled away as scrap.

“That’s a big help,” said Harrell, who gets out of the car to take photos, like a tourist.

The lot next door is surrounded by rusting chain link fence and is overgrown with weeds.

“That’s American Lead,” Harrell said of the former plant, now being used to store concrete forms. The former plant is blamed for contaminating much of Martindale-Brightwood.

Many of the brownfield sites here and across the city are small—an average of 2.3 acres. They’re embedded in neighborhoods.

“It actually makes it harder. It’s like a shotgun [blast] that spreads out your challenges,” Harrell said.

In this area, a brownfield site is never a minute or two away. For example, there’s the former Colonial Bakery vehicle maintenance site at 2444 N. Winthrop Ave. The land is now owned by King Park Area Redevelopment Corp., which has been working with the city to ready it for redevelopment. The buildings have been demolished and four underground storage tanks removed courtesy of $132,000 in Indiana Finance Authority brownfields grants.

Near 22nd Street and Columbia Avenue is a grass-covered, tree-lined site Harrell has tried to protect from illegal dumping. He’s chagrined that someone has pushed aside a barricade.

“This is the future site of the National Apartments,” he said of Development Concepts’ planned project.

Harrell lassoed $60,000 in state brownfield grants to investigate whether the soil is suitable for residential occupation. “It is,” he said.

Development Concepts hopes to break ground on the $7.5 million project as early as next month. It would consist of two, four-story buildings with 62 units. It’s geared not to yuppies but to those of modest incomes already living in the area.

Farther south, at 16th Street and the Monon Trail, the company is developing the Martindale on the Monon neighborhood. It consists of rehabilitated and new houses, starting at $140,000.

But developers aren’t the only ones with designs on brownfields. Harrell drives a bit farther down the street, over an extension cord someone strung to tap power from another house, to the former Production Plating site at 2221 Yandes St. A church that operates a recreation center next door expressed interest in the abandoned building.

That’s easier said than done, of course. The Indiana Department of Environmental Management earlier this year assessed a $15,000 fine against Production Plating’s owner, saying it failed to make hazardous waste determinations on “significant amounts” of liquid and soil wastes throughout the building. That included 26 drums of material.

Before ceasing operation in 2007, the plating site had chemicals including chrome-contaminated waste, corrosives and cyanide solution. Containers were kept open and piles of uncovered wastes were placed on the floor, IDEM said after an inspection that concluded the material “could threaten human health or the environment.”

Harrell rattled off a list of grants that might be available for reuse, and said there are ways to protect the church from any future liability. In his job for six years now, Harrell estimates his office has wrangled 43 grants worth $3.2 million for brownfields projects city-wide.

“I think he eats and sleeps brownfields,” said Josephine Rogers, executive director of Martindale-Brightwood Community Development Corp.

“He’ll say, ‘I was out there on Saturday [to a site.] I was out there on Sunday,’” she recalled.

Of about 500 brownfield sites city-wide, 44 have been redeveloped in recent years and 16 are “development-ready,” Harrell said.

Speeding redevelopment

Until a couple of years ago, Harrell thought the way to revitalize the area would be to marry it to another city initiative. He thought the big catalyst might be converting CSX’s abandoned Bee Line railroad that snakes through Martindale-Brightwood to the city’s trail system.

Harrell later realized the best way to promote faster redevelopment would be to get aboard the momentum of various community organizations—such as Martindale-Brightwood CDC and King Park CDC—and their various economic development projects. All neighborhoods are interconnected, Rogers said. “We can’t work in a vacuum.”

Opportunities for redevelopment have also grown now that city planners have anointed the Nickel Plate as the first corridor for future rail transit. The neighborhood has up to three points that could make for future rail stops.

Further helping was a visit last fall from the American Institute of Architects, with its Sustainable Design Assessment Team, or SDAT. The neighborhood became one of nine in the country where AIA has dispatched experts to look at development potential.

A number of ideas surfaced. One was to look at urban farming potential. That’s a possibility for the former Monon rail yard. Martindale-Brightwood CDC has entertained the idea of community garden plots, outdoor classrooms and even building a barn. Whatever the ultimate use, the city has been dumping large piles of clean soil at the site with the idea of capping the old rail yard.

Cash to advance such ideas could be on its way. The 22nd and Monon area is one of just five nationwide to qualify for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Smart Growth Implementation Assistance facility. It could open up grants from not only the EPA, but also from HUD and the U.S. Department of Transportation.

“If that happens, it could trigger some major reinvestment,” said Ball State’s Beaubien.

He envisions a community with a balance of residential development along with a diversified mix of workplaces. The area around 22nd and the Monon still has a number of manufacturers, such as Indiana Veneers, which has been operating along the Monon for 118 years and is believed to be the oldest sliced veneer mill in North America.

But the neighborhood also needs employers that offer service jobs, something that could come from retail offerings—hardware and grocery stores that are in short supply downtown, Beaubien said.

The area also has potential to serve as a test bed for sustainable development practices—such as properties that absorb storm water runoff to reduce the burden on the city’s sewer system. Or it could showcase LED street lighting, for example. What works could be replicated in other parts of the city.

What Beaubien and others don’t want to do is replicate problems of gentrification that accompanied other redevelopment efforts, such as Fall Creek Place.

How do you encourage investment that doesn’t raise property values to such an extent to force out existing residents who can no longer afford to live there?

“That’s a very tricky question,” Beaubien said. “It’s not envisioned to be a subdivision where everybody looks the same and drives the same car.”

Harrell, in an EPA brownfield planning grant he submitted in June, also seeks money to help create strategies to mitigate gentrification displacement.

“We want to accommodate the current residents first, the current residents and businesses, and then make it desirable for others to join the neighborhood growth,” Harrell said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.