Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe front lobby has a new paint job, featuring lots of “bold blue,” the new corporate color. Just a few steps inside the front door, workers have transformed one wall into a 15-foot-tall nature center, featuring about 1,000 indoor plants, including ferns, ivy and dwarf umbrella trees.

It’s a new look for the 248-acre campus on the city’s northwest side, which has been a key player in Indianapolis life sciences and technology circles for more than three decades, much of that time under the name Dow AgroSciences.

But it now operates under a new name, Corteva Agriscience, following its spinoff June 1 from DowDuPont. The move allows the new company to focus completely on agricultural chemicals, seeds and plant biotechnology, and not think about the multitude of unrelated business lines operated by its former parent company, from plastics and electronics to brake fluids and packaging materials.

Corteva is billing itself as a “pure-play” company, meaning it does business in only one line of business: agriculture.

“Every single day, we’re waking up and thinking about farmers,” said Susan Lewis, Corteva’s senior vice president of enterprise operations. “We’re thinking about the consumers. We’re thinking about the state of agriculture around the world.”

Lewis

Lewis That means it won’t have to fight for corporate money, manpower or other resources against sister operations in unrelated fields, which is how it operated for decades as a unit of Midland, Michigan-based Dow Chemical, and then for the past three years as part of Wilmington, Delaware-based DowDuPont, a company formed from the $130 billion combination of the two huge conglomerates.

That means it won’t have to fight for corporate money, manpower or other resources against sister operations in unrelated fields, which is how it operated for decades as a unit of Midland, Michigan-based Dow Chemical, and then for the past three years as part of Wilmington, Delaware-based DowDuPont, a company formed from the $130 billion combination of the two huge conglomerates.

What the merger means, for Indianapolis, however, is harder to figure out.

Corteva says it plans to stay put at its current site, about 15 miles northwest of downtown. The rolling campus features 14 office buildings, 42 greenhouses and dozens of labs, where workers devise new products to help farmers increase yields and control insects, fungus and unwanted vegetation. “We have every intention of staying here,” said Lewis, during a recent tour of the property for IBJ. “We have a very strong research community, very strong research labs.”

It’s unclear, however, how much the Indianapolis operation, with about 1,500 workers now, will expand in coming years. Lewis, one of the highest-ranking Corteva officials in Indianapolis, said the company’s intention is to grow, but when asked by how much, and over what time period, she declined to offer specifics.

“I don’t think we can project that right this second,” she said.

But state officials have definite ideas about that. In July 2017, the Indiana Economic Development Corp. signed an agreement under which Corteva would “endeavor” to create 600 additional jobs by 2028 in exchange for up to $26 million in conditional tax credits.

Bedel

Bedel“That’s the expectation. That’s what we all hope. That’s the direction we’re going in,” said Elaine Bedel, IEDC’s president, in an interview with IBJ. “But as you know, business sometimes can’t be predicted precisely. These (incentives) are all performance based. You create the job, you get the corporate tax credit once the job is created.”

Consolation prize

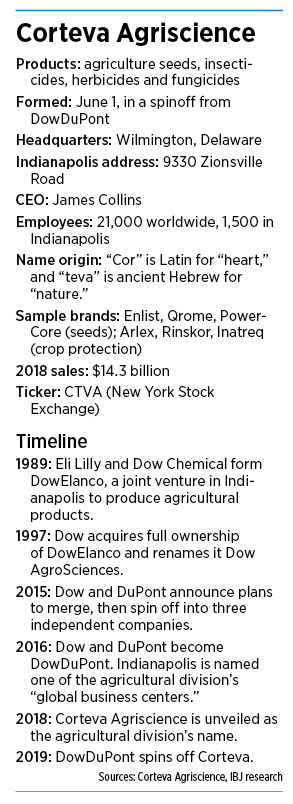

More than three years ago, as the plans for the merger and subsequent spinoff were unfolding, Indiana officials tried to persuade Dow and DuPont to make Indianapolis the headquarters for the merged agricultural operations, which have annual revenue of $14.3 billion and a global workforce of 21,000.

But that didn’t happen. In February 2016, the companies announced that Wilmington, Delaware, would be the headquarters for their combined agricultural businesses, and that Indianapolis would be one of its two “global business centers.” The other center would be in Johnston, Iowa, longtime home to DuPont’s Pioneer seed business.

Despite losing the headquarters contest, Indiana officials said they were pleased with the outcome, because it meant Indiana would continue to be home to more than 1,000 workers, many of them highly paid executives and researchers.

Even though it has offered tens of millions of dollars in its quest to sway the company to create an even larger footprint in Indianapolis, the state will have to compete against other Corteva sites to win jobs here as the company grows. The company operates more than 150 research and development facilities around the world.

Bedel at IEDC said the Indianapolis campus has an advantage by virtue of its long history in developing pesticides, herbicides and fungicides for farmers, which she called a growth area.

“We’re going to be their R&D focus,” she said. “We’re going to be the place where they grow the jobs. That’s my understanding.”

The city of Indianapolis, meanwhile, is giving millions of dollars in incentives for the company to stay in Marion County, without any requirement that the company add a single job.

Last fall, the City-County Council voted to give Corteva $30 million in incentives to stay. Corteva’s only obligation is to keep a workforce of at least 1,385 here for 10 years.

Some city officials said Indianapolis needed to do everything possible to make sure Corteva didn’t abandon the city as it took on a new name under a new corporate structure. So it approached the situation as though it were dealing with a brand-new company, not one that had been doing business here for decades.

“The city viewed this as much about attracting a new business as the retention of existing jobs,” said Thomas Cook, Mayor Joe Hogsett’s chief of staff. “We treated it like we would anybody coming in. … You’ve got to guarantee us a certain level of jobs and as long as you hit that, this is what the incentive package looks like.”

Leroy Robinson, a Democrat who represents the district where Corteva is located, said at the time that he supported the deal because it would have been “devastating” if the company left. But some members of the Indianapolis City-County Council say they’re still upset Indianapolis city agreed to hand over the incentives with no promise for future investments or additional hiring.

Robinson

Robinson“Why are we giving them all these incentives in exchange for no job creation?” said Jared Evans, a Democrat who represents a district on the city’s west side. “The company’s name has changed, but nothing else has changed. There’s no new jobs.”

Cloudy outlook

How much the company can grow remains to be seen.

Scientist Dan Kirk checks on corn with cutworms.(IBJ photos/Eric Learned)

Scientist Dan Kirk checks on corn with cutworms.(IBJ photos/Eric Learned)The farm sector as a whole is facing huge headwinds. Severe flooding and cold weather in recent months have damaged fields, delayed planting and held up crop shipments. Farm commodity prices have plunged in recent years, and U.S. farm income is down 44% from its 2013 peak.

Above that, Corteva is facing specific challenges. The company sells genetically modified products to help farmers control weeds and pests, often by inserting genetic material from one plant species into another. But dozens of countries, from Algeria to Zimbabwe, prohibit the growing of GMO crops, and public opposition is growing. Some consumer groups say GMOs are bad for human health and the environment. In the U.S., some states require that foods grown with GMO technology to be labeled as such.

In April, the African Centre for Biodiversity, an anti-GMO advocacy group lodged an objection to three applications by Corteva for permits in South Africa to allow the commercial sale and growing of genetically modified maize seed that is resistant to certain chemicals, “based on precautionary measures to protect human and environmental health.”

Evans

EvansBut Corteva says genetically engineered crops are safe to eat and do not harm the environment. The company’s position is backed up by a 2016 report from an advisory group to the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, which examined more than 1,000 studies, heard testimony from 80 witnesses and analyzed 700 comments submitted by the public.

The committee said it found no evidence that the crops had contributed to an increase in the incidence of cancer, obesity, diabetes, kidney disease, autism, celiac disease or food allergies, according to a report in The New York Times.

‘Let science win over fear’

Corteva officials say they plan to continue selling GMO products and will step up efforts to spread the message that the technology is safe. “Let science win over fear is the message,” said Rajan Gajaria, Corteva executive vice president for business platforms in Indianapolis.

Beyond that, Corteva will have its hand full trying to clear numerous business and regulatory hurdles. In government filings, Corteva lays out more than a dozen risk factors, from climate change and unpredictable weather to industry consolidation and the volatility of raw materials and production costs, as it sets out as an independent company.

But in recent months, CEO Jim Collins has been crisscrossing the country, meeting with investors with the mantra that the company is blending its teams of scientists, salespeople and other specialists to cut costs and improve productivity.

Gajaria

Gajaria“Despite some of these market headwinds, we’re really executing all the levers that we have in our control,” Collins told CNBC on June 3.

Company officials recently gave IBJ a tour of the campus, including a look at several labs and greenhouses. In one large area called a propagation room, the company grows plants under extremely controlled conditions, including a steady 24-hour-a-day temperature under LED lighting, in an effort to get consistency in physiology, color and height for chemical tests.

“Once the plant gets to a certain height, we will take it to the greenhouse and inoculate it with a pathogen, and then test our product on the plant,” said Vid Hegde, global leader of discovery crop protection.

The first round of testing, he said, helps scientists see if the product kills the disease, stops the insects or controls the weeds. A second round gives further validation. A third round gives deeper insights into how many different pests the chemical might work against, with the goal of having the product work on as wide a spectrum of targets as possible. “Farmers don’t like to spray 10 insecticides,” Hegde said. “They like to spray one, maybe two, to control a spectrum of insects.”

Wall Street sentiment

In recent months, Corteva has won support from some Wall Street analysts, who say the company has the portfolio it needs to compete.

In recent months, Corteva has won support from some Wall Street analysts, who say the company has the portfolio it needs to compete.

Cook

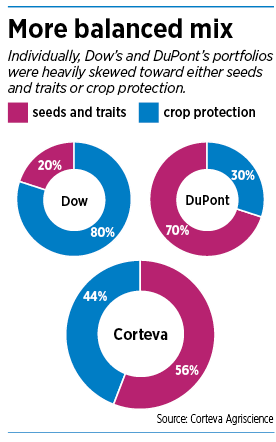

CookCorteva is the largest stand-alone company selling seeds and crop protection to farmers, and the company will have the combined portfolios of Dow agricultural chemicals and seeds, along with DuPont’s Pioneer seeds.

The only agricultural technology company larger than Corteva is German conglomerate Bayer AG, which last year bought agricultural biotech company Monsanto and now has annual agriculture revenues of about $25 million, making it the dominant player in the $100 billion industry. It’s nearly twice as big as Corteva.

Laurence Alexander, analyst for Jefferies LLC, initiated coverage of Corteva with a “buy” rating, and said its Pioneer seed brand is “revered by many growers.”

“In our view, Corteva’s product mix makes it the preeminent play on demand trends and developments in corn seeds and herbicides,” he wrote in a May 29 note.

But whether farmers flock to Corteva remains to be seen. Some farmers have expressed loud opposition to the merger of Dow and DuPont, and the subsequent spinoff of Corteva, saying it eliminated competition and could push up prices.

“Farmers are going to end up paying higher prices for fewer choices,” Roger Johnson, president of the National Farmers Union and owner of a 1,000-acre farm in North Dakota, told IBJ in 2015, shortly after the merger was announced.

And he hasn’t changed his tune. When company officials showed up in New York on June 2 to ring the bell at the New York Stock Exchange, Johnson repeated his concerns. “Corteva Agriscience›s first day as a stand-alone company is … not good for us,” he told The Wall Street Journal.

It’s unclear whether Indiana farmers share his concern. The Indiana Farm Bureau, which represents 70,000 farm families, declined to comment. “We don’t want to speak on members’ behalf on this matter when we aren’t sure their thoughts on it,” spokeswoman Molly Zentz said. “It’s possible that depending on their place in the industry, they have differing opinions.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.