Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThousands of companies have instituted weight loss programs for their workers.

But Hillenbrand Inc. might be the only company to see significant amounts of weight lost by telling its workers to eat more.

The Batesville-based casket maker six months ago instituted a program called Target Metabolism among 125 employees. Based on early results, Hillenbrand is considering expanding the program to all 900 of its workers in Batesville and possibly to some of the rest of its 6,000 workers worldwide.

Run by Greenfield-based On Target Health LLC, the program helps participants drop weight by losing only fat tissue, not muscle or other “lean body mass.”

It does this by determining each participant’s ideal level of daily calorie intake and encouraging them to hit that target. On Target found nearly half the participants weren’t eating enough, especially during their meeting-filled work days.

On Target determines calorie targets by conducting two tests: An indirect calorimeter sees how fast each person’s body burns calories, and a machine called a BodPod—which looks like a space capsule from a sci-fi movie—sees how many pounds of fat each person has.

On Target then gauges success by measuring participants’ fat content every two weeks, and checking their blood sugar and cholesterol every three months.

“I can walk stairs now, where I couldn’t hardly walk them before,” said employee Rosie Calhoun, who has dropped 19 pounds of fat in the past five months. Calhoun, 67, now walks three flights of stairs each day—instead of taking the elevator—to her office in Hillenbrand’s headquarters building.

“I can walk stairs now, where I couldn’t hardly walk them before,” said employee Rosie Calhoun, who has dropped 19 pounds of fat in the past five months. Calhoun, 67, now walks three flights of stairs each day—instead of taking the elevator—to her office in Hillenbrand’s headquarters building.

Calhoun had tried pretty much every weight loss program before—mostly with temporary success.

“I had been on all of those diets. I was even hypnotized one time,” she said. “But at my age now, you tend to not be successful with those things. Your body changes so much.”

During the six months of the On Target program, participants have lost an average of 9-1/2 pounds—or a total of 1,300.

“I can’t wait till we get to 2,000, because I want to say, ‘We’ve lost a ton of weight,’” said On Target Partner Beth Thompson, who leads the program on Hillenbrand’s campus. “Fat tissue causes so many health problems for people. It just needs to be gone.”

Hillenbrand represents a key test of corporate wellness because it offers one of the most comprehensive sets of health care services to employees in corporate America and is doing so at a time employers—about 95 percent of which have some sort of wellness program—are doubling down on the concept because they’re desperate to save money on fast-rising benefits costs. Also, Obamacare is giving employers even more tax incentives to institute wellness programs.

Yet it’s also a time of great skepticism about corporate wellness efforts. Recent research suggests the efforts have almost universally failed and that they influence only a tiny percentage of all spending on health care.

Long-term test

The challenge for Hillenbrand will be to see if the early results hold up for the long term. Thompson, who used to offer the Target Metabolism program through retail stores around Indianapolis, claims that 12 months after the program ends, 74 percent of its clients maintain the weight loss they achieved during the program.

But other programs have seen early gains vanish over time.

Al Lewis, president of the Disease Management Purchasing Consortium in Massachusetts, was stunned to hear about On Target’s program, because it is strikingly similar to a plan tried in the late 1980s on Long Island by a company called United Weight Control. The company offered a liquid diet program, created by a noted obesity researcher named Theodore VanItallie. Lewis was the company’s CEO.

“It didn’t work. Of course,” Lewis said. “People dropped out, and obviously, they gained the weight back. And those who stayed in it, went on weight maintenance, and they gained the weight back” after a couple of years.

From a career in corporate wellness and disease management, Lewis, a health economist, has become one of the nation’s foremost critics of corporate wellness efforts. He and health care consultant Vik Khanna published a book this year titled “Surviving Workplace Wellness,” which declared it a mathematical impossibility for corporate wellness efforts to save money.

Lewis developed a list of medical procedures that can be influenced by wellness efforts. Then he examined the percentage of all medical spending coming from those procedures. His conclusion: about 4 percent.

“Wellness literally cannot save money,” Lewis said. “In health care, the 80-20 rule is that 80 percent of the time, there is no 80-20 rule. Your spending is spread out in so many places.”

Lewis said more corporate chief financial officers—most of whom don’t think wellness saves money, anyway—should know that wellness programs cost about 10 times more than what a company actually pays out for wellness services. That’s because the screening and questioning of employees to find health problems often induces them to get more care, driving up spending in the employer’s health plan.

“It’s about 10 percent of [employers’] health spend,” Lewis said. “The numbers are scattered like the dirt in the Great Escape. It takes a lot of digging, no pun intended, to find it all.”

It takes a village

Of course, not everyone is convinced by Lewis’ critique.

Todd Foushee, vice president of business development for Quad Medical, the Wisconsin-based company that operates Hillenbrand’s on-site health clinic, said Hillenbrand is a leading example of the kind of comprehensive program that works.

“It really does take a village to reverse the trends,” said Foushee. “Combine all the services and those patients who are ready to change will seize the opportunity. Many patients are prisoners of their bodies and need an integrated solution to address the physical and mental aspects of the issue.”

He has research to back him up. A 2010 review of wellness studies conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that comprehensive wellness programs—which account for only about 7 percent of all corporate wellness programs—did help improve workers’ health and save employers money.

The On Target program links in with all the other things Hillenbrand has done to improve its workers’ health over the past six years: an on-site medical clinic, high-deductible health plans and programs to help employees schedule diagnostic and specialty consults while considering the difference in cost and quality among various health care providers.

That suite of services is key in helping workers get healthier, Foushee and Thompson said. That’s true first because the On Target program easily operates under the oversight of the physicians that staff Hillenbrand’s clinic.

Rosie Calhoun, a 46-year worker at Hillenbrand, comes twice a month for check-ups of her body fat in the BodPod. She has lost 19 pounds. (IBJ Photo/Eric Learned)

Rosie Calhoun, a 46-year worker at Hillenbrand, comes twice a month for check-ups of her body fat in the BodPod. She has lost 19 pounds. (IBJ Photo/Eric Learned)Those physicians conduct an initial physical and round of blood tests with each On Target participant, then another physical and set of blood tests at the end.

Having a suite of services is also key because employees often plateau in their efforts to be healthier.

When a Hillenbrand worker stops losing weight, Thompson checks for physiological reasons—such as whether the employee’s metabolism has shifted because of the weight loss or if certain medications are no longer necessary.

She’ll also check to see if there is a mental issue. If so, Hillenbrand has a counseling program. Or physicians at the clinic can set up an appointment with a mental health worker.

QuadMedical’s Foushee said having medical professionals make appointments for workers is key, because only about one in seven workers will actually schedule and go to a mental health professional simply because a doctor recommended it.

Costs contained

Julie Joerger, Hillenbrand’s director of mergers and acquisitions and human resources services, credits the changes with limiting Hillenbrand’s health benefits spending to about 3 percent to 5 percent per year.

Since 2008, employer spending on benefits rose 3 percent to 11 percent per year, according to an annual nationwide survey by California-based Kaiser Family Foundation.

Joerger doesn’t talk about On Target’s weight loss program primarily as another attempt to control costs. Instead, she said she embraced it when Foushee and Thompson approached her as a way to keep employees focused on health and wellness.

“You’ve always got to be asking, ‘What’s next?’” Joerger said. “Because employees, they do a weight loss program or an exercise program and then it ends and they say, ‘OK, now what do I do?’”

On Target has contributed to that culture of wellness at Hillenbrand, employees said.

“At company meetings, people still order the pizza, but now there’s a big salad ordered with it. Or when we have birthday parties, there is still cake and candy, but now there will be fruit, too. Because they know people are going to be watching their calories,” said Todd Tekulve, manager of Hillenbrand’s Batesville casket products. He has lost 38 pounds on the program since June.

Joerger and her fellow executives at Hillenbrand will decide whether to expand the On Target program based on its clinical results.

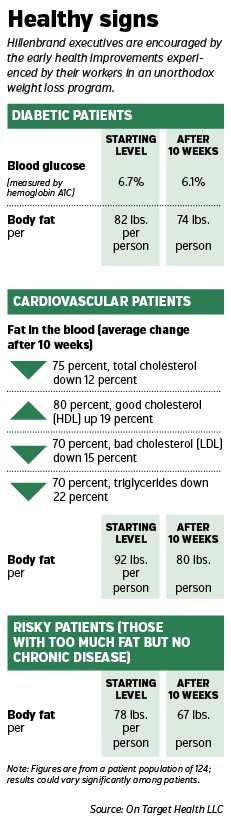

So far, all six diabetic and pre-diabetic patients in the program saw their blood sugar levels—measured by the blood particle hemoglobin A1C—go down. The average drop was 0.6 percent over 10 weeks, which, if continued, would be similar in effectiveness to many diabetes medications.

The diabetic and pre-diabetic patients also lost eight pounds on average in the program’s first 10 weeks.

Among the 20 patients with poor cholesterol and triglyceride levels, 16 increased their HDL, or “good,” cholesterol, by an average of 19 percent; 14 decreased their LDL, or “bad,” cholesterol, by an average of 15 percent; and 14 decreased their triglycerides, by an average of 22 percent.

“Right now, it’s looking pretty good,” Joerger said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.